Antigen

An antigen ("anti", from the Greek αντι- meaning 'opposite' or 'with opposite properties' and &# 34;geno", from the Greek root γεν, to generate, to produce; that generates or creates opposition) is a substance that can be recognized by the receptors of the adaptive immune system. The old definition was limited to substances capable of generating the production of antibodies and triggering an immune response, but the modern definition takes into account T-lymphocyte receptors, plus the ability to generate an immune response is attributed to the definition of immunogen.

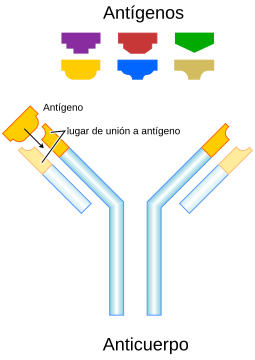

An antigen is usually a foreign or toxic molecule to the body (for example, a protein derived from bacteria) that, once inside the body, attracts and binds with high affinity to a specific antibody. Each antibody is capable of specifically dealing with a single antigen thanks to the variability provided by the antibody's complementarity-determining region within its Fab fraction.

For an antigen to be recognized by an antibody, they interact by spatial complementarity. The area where the antigen binds to the antibody is called the epitope or antigenic determinant, while the corresponding area of the antibody molecule is the paratope. (A common analogy to describe these interactions is the coupling of a lock [epitope] with its key [paratope]).

As mentioned above, an antigen was originally considered to be a molecule that specifically binds to an antibody; An antigen is now defined as any molecule or molecular fragment that can be recognized by a wide variety of antigen receptors (T-cell receptors or B-cell receptors) of the adaptive immune system. Cells present antigens to the immune system through the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). Depending on the antigen presented and the type of histocompatibility molecule, different types of leukocytes can be activated. For example, for recognition by T cell receptors (TCRs), antigens (mostly proteins) must be processed into small fragments within the cell (peptides) and presented to the T cell receptor by the major histocompatibility complex.

Antigens alone are not capable of eliciting a protective immune response without the aid of an immunological adjuvant. The adjuvant components of vaccines play an essential role in the activation of the innate immune system. An immunogen is thus, analogous to antigen, a substance (or combination of substances) capable of eliciting a protective immune response when introduced into the body. An immunogen must initiate an innate immune response, followed by activation of the immune system later adaptive, whereas an antigen is capable of binding to highly variable immunoreceptor products (T-cell receptors or B-cell receptors) once they have been produced. The overlapping concepts of immunogenicity and antigenicity are therefore slightly different,

- Immunogenicity is the ability to induce a humoral immune response (antibody production) and/or a mediated cell (activation of T lymphocytes).

- Antigenicity is the ability to join specifically with the final product of the immune response (e.g., already formed antibodies and/or T-cell surface receptors). All immunogenic molecules are also antigenic; yet not all antigenic molecules are immunogenic.

Antigens are usually proteins or polysaccharides. This includes parts of bacteria (capsule, cell wall, flagella, fimbriae, and toxins), viruses, and other microorganisms. Lipids and nucleic acids are antigenic only when combined with proteins and/or polysaccharides. Exogenous (non-individual) nonmicrobial antigens can be pollen, egg white, and proteins from transplanted tissues and organs or proteins on the surface of transfused red blood cells. Vaccines are an example of antigens in an immunogenic form; these antigens are intentionally administered to induce the memory phenomenon of the adaptive immune system towards the antigens invading the recipient.

Related concepts

- Epitopo – The different surfaces of an antigen capable of being recognized by different antibodies (with different complementary regions). Antigenic molecules, usually “large” biological polymers, usually present many surfaces with different characteristics that can act as interaction points for specific antibodies. Any of these distinctive molecular surfaces constitutes an antigenic epitope or determinant. Therefore, most antigens have potential to be recognized by several different antibodies, each of them specific to a particular epitope.

- Allergen – Substance capable of causing an allergic reaction. The reaction (detrimental) may occur after exposure via oral, inhaled, parenteral, or contact with the skin.

- Superancient – It is a type of antigen that causes an inspecific activation of T lymphocytes, resulting in a polyclonal activation of T lymphocytes and a massive release of cytokines.

- Tolergen – It is a substance that, due to its molecular structure, does not trigger an immune response. If your molecular structure changes, a tolergen can become an immunogen.

- Proteins that unite immunoglobulins – These proteins are able to join an antibody outside the antigen binding site. This means that while antigens are the target of antibodies, the immune-globulin binding proteins “attack” antibodies. Protein A, G protein and L protein are examples of proteins that are strongly linked to different antibody isotypes.

- T-dependent antigens – T-dependent antigens are usually protein. They require the collaboration of T lymphocytes to induce the formation of specific antibodies.

- T-independent antigens – T-independent antigens are usually polysaccharides that stimulate B lymphocytes directly.

- Immunodominant antigens – They are the antigens that dominate (on the other antigens of the same pathogen) in their ability to produce an immune response. It is commonly assumed that the responses by T cells are directed towards only a few immunodominant epitopes, although in some cases such responses (e.g. the response against Plasmodium spp.) are dispersed to a relatively large group of parasite antigens.

Origin of antigens

Antigens can be classified according to their origin. Antigens can have three origins.

Exogenous Antigens

Exogenous antigens are antigens that have entered the body from outside, for example through inhalation, ingestion or injection. Often the immune response to foreign antigens is subclinical. These antigens are taken up by antigen presenting cells (APCs) by endocytosis or phagocytosis and processed into fragments. The APCs will then present these fragments to helper T cells (CD4+) with the help of class II histocompatibility molecules on their surface. T lymphocytes that specifically recognize the peptide: MHC duo are activated and begin to secrete cytokines. Cytokines are substances that in turn can activate cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+), antibody-producing cells or B lymphocytes, macrophages, and others.

Some antigens enter the body as exogenous antigens and then become endogenous antigens (for example, an intracellular virus). Intracellular antigens can be released back into the bloodstream once the infected cell is killed.

Endogenous Antigens

Endogenous antigens are those antigens that have been generated within a cell as a result of normal cellular metabolism or due to intracellular viral or bacterial infections. Fragments of these antigens are presented on the cell surface in a complex with MHC class I molecules. If recognized by activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+), they will begin to secrete various toxins that will cause the lysis or apoptosis (cell death) of the infected cell. To prevent cytotoxic cells from killing normal cells that present the body's own proteins, these autoreactive T cells are removed from the repertoire as a result of tolerance (also known as negative selection). Endogenous antigens can be xenogenic (heterologous), autologous, idiotypic, and allogeneic (homologous).

Autoantigens

An autoantigen is a normal protein or protein complex, sometimes also DNA or RNA, that is not recognized by the immune system. It occurs in patients suffering from a specific autoimmune disease. These antigens should not, under normal conditions, activate the immune system, but in these patients, due mainly to genetic and/or environmental factors, their correct immunological tolerance has been lost.

Tumor antigens

The tumor antigens or neoantigens are those antigens that are presented by MHC I or MHC II molecules (of the major histocompatibility complex) found on the surface of cells tumors. When these types of antigens are presented by cells from a tumor they are called tumor specific antigens (TSAs for its acronym in English ) and, generally, they are the result of a specific mutation. Most commonly there are antigens that are presented by normal and tumor cells, called tumor-associated antigens (TAAs for its acronym in English ). Cytotoxic T lymphocytes that recognize these antigens are able to kill the tumor cell before it proliferates or metastasizes.

Tumor antigens can also be on the surface of a tumor, forming, for example, a mutated receptor, in which case it will be recognized by B lymphocytes.

Native Antigens

A native antigen is an antigen that is still in its original form and has not been processed into smaller parts by a CPA.

T lymphocytes cannot bind to native antigens, since they need the help of APCs to process them, while B lymphocytes can be activated by this class of antigens.

Antigen Specificity

Antigenic specificity is the ability of the host to specifically recognize an antigen as a single molecular entity and to distinguish it from others with exquisite precision. Antigenic specificity is mainly due to the conformation of the antigen side chains (side chains of the amino acids that make up proteins, for example). Such specificity can be measured, although not necessarily easily because the antigen-antibody interaction can behave in a non-linear manner.

Contenido relacionado

Dasyuromorphia

Droseraceae

Acrobatidae