| Oral heritage and cultural manifestations of the Zapara people |

| Good. immaterial registered in 2008 (originally proclaimed in 2001).

|

This element is shared with Ecuador Ecuador Ecuador |

The Zapara people live in a region of the Amazon rainforest between Peru and Ecuador. In one of the most rich regions of the world in biodiversity, the Zeparas are the last representatives of an ethnolinguistic group that included many other populations before the Spanish conquest. In the heart of the Amazon, they have developed an oral culture that is particularly rich in knowledge of its natural environment, as evidences the abundance of its terminology about flora and fauna and its knowledge of the medicinal plants of the jungle. This cultural heritage is also expressed through myths, rituals, artistic practices and their language. This, which is the depository of its knowledge and its oral tradition, also represents the memory of the entire region.

Four centuries of history marked by the Spanish conquest, slavery, epidemics, forced conversions, wars or deforestation have decimated this people. However, despite so many threats, the Zeparas have been able to obstinately preserve their ancestral knowledge. Through marriages with other indigenous peoples (chuas and mestizos), this people have managed to survive. But this dispersion also implies the loss of a part of your identity.

The current situation of the Zapara people is critical and the risk of extinction is not excluded. In 2001, the number of záparas did not exceed 300 (200 in Peru and 100 in Ecuador), of which only 5, more than 70 years old, still speak the Zopara language. (UNESCO/BPI)

|

| The Textile Art of Taquile |

| Good. immaterial registered in 2008 (originally proclaimed in 2005).

|

The island of Taquile is located in the Peruvian Andean highland, on Lake Titicaca, and is known for its textile craftsmanship made by men and women of all ages, whose products are used by all members of the community.

The population of Taquile lived relatively isolated from the continent until the 1950s, and the notion of community remains very strong among them. This is reflected in the organization of community life and collective decision-making. The tradition of weaving on the island of Taquile dates back to ancient inca civilizations, pukara and colla, so it keeps alive elements of the pre-Hispanic Andean cultures.

Fabrics are made by hand or in pre-Hispanic pedal looms. The most characteristic garments are the chullo, a knitted hat with orejeras, and the swab-calendary, a wide belt that represents the annual cycles associated with ritual and agricultural activities. The belt-calendar has attracted the interest of many researchers, as it represents elements of the oral tradition of the community and its history. Although Taquile's textile art design has introduced new contemporary symbols and images, traditional style and techniques are still maintained.

Taquile has a specialized school to learn local crafts, which contributes to the viability and continuity of tradition. Tourism has contributed to the development of the community economy, which is mainly based on textile trade and tourism. While tourism is regarded as an effective way of ensuring the continuity of textile tradition, growing demand also translates into significant changes in material, production and meaning. Taquile's population has grown considerably over the past few decades, resulting in a shortage of resources and the need to import more and more products from the continent. (UNESCO/BPI)

|

| The Scissors Dance |

| Good. immaterial proclaimed in 2010.

|

The dance of the scissors has been traditionally interpreted by the inhabitants of the Quechuas peoples and communities of the south of the central Andean mountain range of Peru and, for some time, by populations of the urban areas of the country. This ritual dance, which takes the form of a competition, is danced during the dry season of the year and its execution coincides with important phases of the agricultural calendar. The dance of the scissors owes its name to the two rotten metal leaves, similar to those of the scissors, that the dancers blanden on their right hand. The dance runs in squares and each one of them – formed by a dancer, an arpist and a violinist – represents a particular community or people. In order to interpret the dance, they face to face two squares at least and the dancers, at the rhythm of the melodies interpreted by the musicians who accompany them, have to mask the metal leaves and deliver a choreographic duel of dance steps, acrobatics and increasingly difficult movements. That duel among the dancers, called atipanakuy in quechua, can last up to ten hours, and the criteria to determine who the winner is: the physical capacity of the performers, the quality of the instruments and the competition of the musicians who accompany the dance. The dancers, who wear embroidered garments with golden strips, lentils and mirages, are forbidden to penetrate into the precinct of the churches with this clothing because their abilities, according to tradition, are the fruit of a covenant with the devil. This has not prevented the scissors' dance from becoming an appreciated component of Catholic festivities. The physical and spiritual knowledge implicit in dance is transmitted orally from teachers to students, and each dancer and musician group is a source of pride for the peoples of which it is native. (UNESCO/BPI)

|

| The Huaconada, ritual dance of Mito |

| Good. immaterial proclaimed in 2010.

|

The huaconada is a ritual dance that is represented in the village of Mito, belonging to the province of Concepción, located in the central Andean mountain range of Peru. The first three days of the month of January of each year, groups of masked men, called huacones, perform in the center of the village a series of choreographed dances. The huacones represent the old council of elders and become the highest authority of the people as the huacon lasts. They highlight this function both their whips, called “troners”, and their masks of prominent noses that evoke the peak of the condor, a creature that represents the spirit of the sacred mountains. Two kinds of huacones are involved in the dance: the elders, dressed in traditional costumes and carriers of finely sculpted masks that infuse respect and fear; and the younger ones, ridiculed with colored clothing and masks that express terror, sadness or mockery. During the huaconada, the latter perform a series of strictly limited dance steps around the elderly who, due to their age, enjoy greater freedom to improvise movements. An orchestra plays various rhythms in the “tinya”, an indigenous drum. The huaconada, which is a synthesis of various Andean and Spanish elements, also integrates new modern elements. Only men of good conduct and great moral integrity can be strikers. Dance is traditionally transmitted from parents to children and dresses and masks are inherited. (UNESCO/BPI)

|

| Eshuva, singing prayers of the Huachipaeri ethnic group |

| Good. immaterial registered in 2011 on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage that requires urgent safeguard measures.

|

The Huachipaeri are an indigenous ethnic group that speaks the Harakmbut language and live in the tropical jungle of southern Peru. The Eshuva prayer is part of the Huachipaire religious myths that are performed as part of traditional ceremonies. According to oral tradition the songs of Eshuva were learned directly from forest animals, and with them the spirits of nature are invoked to help relieve diseases or discomforts, and promote well-being. The song of Eshuva has no instrumentation and is sung only in Harakmbut. As such they represent a key factor in safeguarding the language and preserving the values of the group and its vision of the world. The teaching of Eshuva is done by mouth. The Eshuva is at risk of losing itself because the transmission has been interrupted due to the lack of interest of the young Huachipaeri in learning it, in addition to the strong internal migration and assimilation of external cultural elements. There are currently only 12 known singers among the Huachipaeri. (UNESCO/BPI)

|

| The pilgrimage to the shrine of the Lord of Qoyllurit’i |

| Good. immaterial proclaimed in 2011.

|

In the pilgrimage to the shrine of the Lord of Qoyllurit’i (Lord of the Star of Snow) elements from Catholicism and worship are mixed with the pre-Hispanic gods. This pilgrimage begins fifty eight days after the celebration of the Easter Sunday of Resurrection, when some 90,000 people from the surroundings of Cusco are set in motion to the sanctuary, located in the fundonada of Sinakara. The crowd of pilgrims is divided into eight “nations”, corresponding to their peoples of origin: Paucartambo, Quispicanchi, Canchis, Acomayo, Paruro, Tawantinsuyo, Anta and Urubamba. The pilgrimage includes processions with crosses that go up to the snowy summit of the mountain to then descend, and also a procession of twenty-four hours duration in which the Paucartambo nation and the Quispicanchi nation bring to the people of Tayancani the images the Dolorous Virgin and the Lord of Tayancani, in order to celebrate the appearance of the first rays of the sun. Dance plays a fundamental role in the pilgrimage and some one hundred different dances, representative of the different nations, are executed. The Council of Pilgrims Nations and the Brotherhood of the Lord of Qoyllurit’i organize the activities of the pilgrimage, establish their rules and codes of conduct, and provide the necessary food. The maintenance of the order takes care of pablites or pabluchas, characters dressed in alpaca garments that carry masks of animals woven with wool. The pilgrimage encompasses a wide variety of cultural expressions and offers a meeting place for communities settled at different heights of the Andes Mountain Range that are dedicated to different economic activities.(UNESCO/BPI)

|

| Knowledge, techniques and rituals linked to the annual renewal of the Q’eswachaka bridge |

| Good. immaterial registered in 2013.

|

The Q’eswachaka rope hanging bridge unites the two slopes of a Apurímac river cliff, located in the southern Andes of Peru. Every year it is renewed using traditional raw materials and techniques that date back to the inca times. The Quechuas peasant communities of Huinchiri, Chaupibanda, Choccayhua and Ccollana Quehue consider that this work in common is not only a means to maintain in good condition a way of communication, but it is also a way of narrowing the social ties that exist between them. The bridge is considered a sacred symbol of the bond that binds communities with nature and its history and traditions, hence its annual renewal is accompanied by the celebration of ritual ceremonies. Although the renovation of the bridge only lasts three days, it actually structure the lives of the participating communities throughout the year, as it allows them to communicate among themselves, strengthen their secular ties and reaffirm their cultural identity. The renovation begins with the work of the families of the communities, who cut straw and train it in ropes of about seventy meters long. Under the supervision of two master builders, these ropes are intertwined to form the six strings of great thickness that serve as a frame to the bridge. Then the men of the communities solidly bind them to the old stone bases located on each side of the cliff. Two master weavers then direct and perform the tissue of the rest of the bridge's lace, advancing from the two opposite ends of the bridge. Once the bridge is over, the communities celebrate the completion of the work with a party. The fabric techniques of the bridge laces are taught and learned within the families. (UNESCO/BPI)

|

| The feast of the Virgin of the Candelaria in Puno |

| Good. immaterial registered in 2014.

|

Celebrated in the month of February of each year in the city of Puno, the feast of the Virgin of the Candelaria includes acts of a religious, festive and cultural character that have its roots in Catholic traditions and symbolic elements of the Andean cosmovision. The festivities begin in the first month with the celebration of a mass at dawn, followed by an ancestral purification ceremony. The next day in the morning, after a liturgical act, an image of the Virgin of the Candelaria is transported to make her walk in procession the streets of the city with the accompaniment of traditional dances and musics. Then the festivals continue with the celebration of two contests in which some 170 groups from all over the region compete, which total approximately 40,000 dancers and musicians. The main participants in these contests are the Quechua and Aymara ethnic inhabitants of the rural and urban areas of the Puno region. Many people from Puno who emigrated from the region return to this for the feasts of the Candelaria, which contributes to strengthening in them a feeling of cultural continuity. Three regional federations of practitioners of this element of cultural heritage collaborate in the organization of festivities and in the preservation of traditional techniques and knowledge related to dance, music and the manufacture of masks. The transmission to younger generations of all such knowledge is done through the organization of musical and choreographic essays, and also through the creation of workshops for the manufacture of masks. The holidays end with a ceremony in honor of the Virgin, a concert and farewell Masses. (UNESCO/BPI)

|

| The dance of the wititi of the Colca Valley |

| Good. immaterial registered in 2015.

|

The wititi dance of the Colca Valley is a traditional popular dance that relates to the beginning of adulthood. It covers the form of a ritual of loving courtship and is often interpreted by young people during the religious festivities that take place throughout the rainy season. Dancers and dancers are lined up in rows and perform various steps to the music. The dancers wear finely embroidered suits with natural motifs of colorful and are touched with characteristic hats. For their part, the dancers wear two skirts of superimposed woman, a military shirt, a shawl and hats with adiments. The representation of wititi coincides with the beginning of the agricultural production cycle and symbolizes the renewing of nature and society. This dance consolidates the social ties and identity of the villages of the Colca valley, which compete to present the best dance sets, thus continually renewing it and perpetuating its traditional character. Children and young people learn wititi by direct observation, both at schools and at family parties held on the occasion of baptisms, birthdays and weddings. At the national level, there are folk dance groups that also interpret this dance because it has been integrated into their choreographic repertoires. (UNESCO/BPI)

|

| Traditional Corongo Water Judges System |

| Good. immaterial registered in 2017.

|

The Traditional System of Corongo Water Judges is an organizational structure created by the inhabitants of this city of northern Peru, which manages the water supply and cultivates historical memory at the same time. The origins of this system date back to the pre-inca period and its primary objective is to achieve equitable and sustainable water supply, as well as adequate land management, so that future generations can continue to enjoy these two essential natural resources in good condition. The main depositaries of this element of cultural heritage are the inhabitants of Corongo, as this system regulates their agricultural activities. Its highest authority is the water judge, who is responsible for the management of water resources and the organization of the most important festivals in the city. Pilar of the cultural identity and the historical memory of the chornguines, the system is based on three fundamental principles: solidarity, equity and respect for nature. The meaning, importance, functions and values of the system are transferred to the new generations within the families and public institutions, and also in the educational centers of all levels of teaching by learning the emblematic dances of Corongo, intimately linked to this element. Among the values transmitted is the knowledge of the relationship of Saint Peter, the patron of the city, with water and, therefore, with prosperity and well-being. This knowledge is acquired from childhood through oral tradition or participation in religious celebrations. (UNESCO/BPI)

|

| The ‘Hatajo de Negritos’ and ‘Las Pallitas’, dances from the south of the central coast of Peru |

| Good. immaterial registered in 2019.

|

The “Hatajo de Negritos” and “Las Pallitas” are two complementary dances, from the Department of Ica, danced in the south of the central coast of Peru. With music and songs, these cultural expressions are part of the Christmas celebrations. They are biblical representations of the visit of the shepherds to the Child Jesus and of the arrival of the Magi in which three cultural currents are mixed: the values of the pre-Hispanic Andean world, the European Catholicism and the legacy of the musical rhythms of those of Africans brought to this part of Peru in the colonial period. These two dances, representative of the identity of Afro-Peruvians and Mestizos, emerged from this complex confluence of various cultures. The “Hatajo de Negritos” is danced by men zapateando al son de un violin y de campanillas, while singing songs. Instead, the dance of “Las Pallitas” is performed by women who zap and sing to the sound of a guitar. Considered true symbols of religious devotion and spiritual contemplation, both dances are practiced in group and can gather up to half a hundred dancers. During the months of December and January, the public squares and churches of many localities, as well as some family homes, are covered. Young generations are familiar with these two expressions of living cultural heritage from the earliest childhood. Encouraged by adults, children learn in a sign of devotion to sing numerous Christmas carols, as well as to sneak and execute dance steps. (UNESCO/BPI)

|

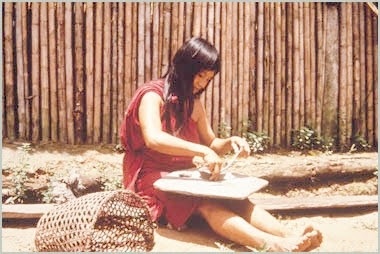

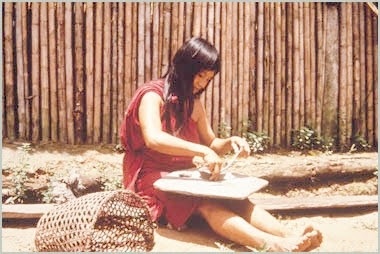

| Values, knowledge, knowledge and practices of the Hawaiian people associated with ceramic production |

| Good. immaterial registered in 2021.

|

The Awajun people of northern Peru consider that the art of pottery is a paradigm of their harmonious relationship with nature. The ceramic manufacturing process includes five phases: the collection of raw material, modelling, cooking, ornamentation and finishing. Each of these phases has a special meaning and is associated with a series of values transmitted by oral tradition. The production of ceramic objects requires special knowledge and mastering particular techniques to create and decorate them. The crafts that manufacture them use a series of specific instruments: crushing and feeding stones, wooden boards, a modeling utensil and a brush whose hair is made of human hair. Decorated with geometric shapes inspired by elements of nature such as plants, animals, mountains and stars, the containers manufactured serve to cook, eat, drink and serve meals, but are also used in the celebration of rituals and ceremonies. This millennial practice of the people of Hawaii not only expresses the personality, generosity and intimate life of those who perform it, but has also played an important social function because it has offered their women the possibility of being empowered, by assuming their manufacture and ornamentation while planting and cultivating the plants used in those tasks. The main depositaries of the knowledge, knowledge and practices of this element of immaterial cultural heritage are the “dukúg”, wise old women who transmit them from generation to generation to the other women of their families. (UNESCO/BPI)

|