Animism

Animism (from the Latin anima, 'soul') is a concept that encompasses various beliefs in which both objects (utilities for daily use or those reserved for special occasions) like any element of the natural world (mountains, rivers, the sky, the earth, certain places, spirits, rocks, plants, animals, trees, etc.) are endowed with movement, life, soul or consciousness of their own.

Although within this conception multiple variants of the phenomenon would fit, such as the belief in spiritual beings, including human souls, in practice the definition extends to personified supernatural beings, endowed with reason, intelligence and will, inhabiting the inanimate objects and govern their existence. This can simply be expressed as everything is alive, conscious, or has a soul.

Although each culture has its own different mythologies and rituals, it is said that "animism" describes the most common underlying thread of "spiritual" or "supernatural" of the indigenous peoples. The animist perspective is so extensive and inherent to most indigenous peoples that they often do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to "animism" (or even "religion"); the term is an anthropological construct.

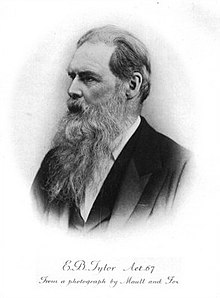

In large part because of such ethnolinguistic and cultural discrepancies, there has been debate over whether "animism" it refers to an ancestral mode of experience common to indigenous peoples around the world, or to a full-blown religion. The currently accepted definition of animism was developed in the late 19th century (1871) by Sir Edward Tylor, who created it as & #34;one of the first concepts in anthropology, if not the first".

Animism encompasses the belief that all material phenomena have agency, relating to and forming a universal anima ("Anima mundi"), and that there is no hard and fast distinction between fast; even traditions like those present in Japan, go further, and for example we can find the belief of soul in the created objects, mainly in the ancient (Tsukumogami); or even in the acts performed, such as the words of speech through the concept of Kotodama (the power of the word).

In America we can find, for example, the belief in the Ngen (spirits of nature).

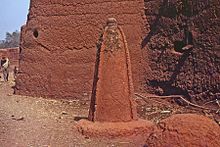

In Africa, animism is found in its most complex and finished version, thus it includes the concept of magara or universal vital force, which connects all animated beings, as well as the belief in a close relationship between the souls of the living and the dead.

Neopagans sometimes describe their belief system as animistic; an example of this idea is that the mother goddess and the horned god coexist in all things. Likewise, pantheists equate God with existence.

The term is also the name of a theory of religion proposed in 1871 by anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor in his book Primitive Culture.

Origins and geographic location

Traces of animism are found in sub-Saharan Africa, Australia, Oceania, Southeast and Central Asia, and throughout the Americas. Archeology and anthropology study the animism currently present in indigenous cultures. Some ancient concepts about the soul can be analyzed from the terms with which it was called. For example, readers of Dante are familiar with the idea that the dead have no shadow (ombra). This was not an invention of the poet but a notion that comes from pre-Christian folklore.

In the Canary Islands, the Canarian aborigines professed an animistic religion (Guanche mythology).

In South America, the Mapuche people profess animism through their belief in the Ngen, nature spirits; which maintain the balance and order between nature (Ñuke Mapu) and human beings. The Ngen being one of the main beliefs together with the cult of the ancestors (called rogue spirits).

In Africa, the Basutos maintain that a person who walks along the bank of a river can lose his life if his shadow touches the water, since a crocodile could swallow it and drag the person into the water.

In the East, the Bön tradition and Shinto stand out.

In some tribes of North and South America, Tasmania and classical Europe, there is the concept that the soul —σκιά, skiá, umbra— is identified with the shadow of a person

On the other hand, in western culture there is a connection between the soul and the breath. This identification is found in both the Indo-European languages and the Semitic languages. Air in Latin is said spiritus; in Greek, pneuma and in Hebrew, ruach. This idea is also found in Australia, various points in pre-Columbian America and Asia.

For some Native American cultures and early Roman religions, the custom of receiving the last breath of a dying man was not only a pious duty but a means of ensuring that his soul would be reincarnated in the womb of a new mother, and would not remain as a wandering ghost. Other known concepts identify the soul with the liver, with the heart, with the figure that is reflected in the pupil of the eye, and with blood.

Although sometimes the soul or vital principle of the body (which animals would also possess) is distinguished as something different from the human spirit, there are cases in which a state of unconsciousness is explained as due to its absence. The indigenous people of South Australia say wilyamarraba (without a soul) to a person who has fainted.

Also, the autohypnotic trance of a shaman or a prophet is believed to be due to his visit to the afterlife, from where he brings prophecies and news of dead people. Telepathy or clairvoyance, with or without trance, can be operated to produce the conviction of the dual nature (material-spiritual) of the human being, since it made it seem possible that facts unknown to the medium could be discovered by means of a ball of Cristal.

Sickness is often explained as the absence of the soul and sometimes certain measures are taken to attract the wandering soul back. In Chinese tradition, when a person is near death and the soul is believed to have left his or her body, the patient's coat is held up on a long bamboo pole while a priest endeavors to return the spirit to the coat by means of of spells. If the bamboo begins to spin in the hands of the relative who has arranged to hold it, this is considered a sign that the soul of the dying person has returned.

Theories

The ancient views of animism, which have since been dubbed the "old animism," had to do with the knowledge of what is alive and what factors make something alive. The 'old animism' assumed that animists were individuals who could not understand the difference between people and things. Critics of the "old animism" they have accused him of preserving the "colonialist and dualist rhetoric and worldview".

Definition of Edward Tylor

The idea of animism was developed by anthropologist Edward Tylor in his 1871 book "Primitive Culture",(EB 1878) in which he defined it as "the general doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings in general". According to Tylor, animism often includes "an idea of penetrating life and will into nature"; a belief that non-human natural objects have souls. That formulation was slightly different from that proposed by Auguste Comte as "fetishism," but the terms now have different meanings.

For Tylor, animism represented the first form of religion, being situated within an evolutionary framework of religion that has developed in stages and will eventually lead humanity to reject religion altogether in favor of rationality scientific. Thus, for Tylor, animism was viewed fundamentally as an error, a basic error from which all religion arose. He did not believe that animism was inherently illogical, but suggested that it arose from the dreams and visions of early humans and, therefore, it was a rational system. However, he relied on erroneous and unscientific observations about the nature of reality.Stringer points out that his reading of "Primitive Culture"; led him to believe that Tylor was much more sympathetic to "primitive" that many of his contemporaries and that Tylor did not express any belief that there was any difference between the intellectual capacities of "savage" people; and Westerners.

Tylor had initially wanted to describe the phenomenon as "spiritualism," but realized that would cause confusion with the modern stream of spiritualism, then prevalent in Western nations. He adopted the term &# 34;animism" from the writings of the German scientist Georg Ernst Stahl, who, in 1708, had developed the term animismus as a theory biological belief that souls formed the vital principle and that the normal phenomena of life and the abnormal phenomena of disease could be traced to spiritual causes. The first known usage in English appeared in 1819.

Archaeologist Timothy Insoll has dismissed the idea that there was ever "a universal form of primitive religion" (either labeled "animism", "totemism" or "shamanism") as "unsophisticated" and "wrong". ], who stated that it "eliminates complexity, a precondition of religion now, in all its variants".

Social evolutionist conceptions

Tylor's definition of animism was part of a growing international debate about the nature of "primitive society" by lawyers, theologians and philologists. The debate defined the research field of a new science: anthropology. In the late 19th century, an orthodoxy of "primitive society" emerged, but few anthropologists would still accept that definition. The "armchair anthropologists of the 19th century" argued that "primitive society" (an evolutionary category) was ordered by kinship and divided into exogamous descent groups related by a series of marriage exchanges. Their religion was animism, the belief that species and natural objects had souls. With the development of private property, descent groups were displaced by the rise of the territorial state. These rituals and beliefs eventually evolved over time into the great variety of 'developed' religions. According to Tylor, the more scientifically advanced a society became, the fewer members of that society believed in animism. However, any remaining ideology of souls or spirits, for Tylor, represented "survivals" of the original animism of primitive humanity.

In 1869 (three years after Tylor proposed his definition of animism), the Edinburgh solicitor John Ferguson McLennan argued that the animistic thought evident in fetishism gave rise to a religion he called Totemism. He argued that primitive people believed that they were descended from the same species as their totemic animal.Later debates among "armchair anthropologists" (including J. J. Bachofen, Émile Durkheim, and Sigmund Freud) remained focused on totemism rather than animism, with few directly challenging Tylor's definition. In fact, anthropologists "have routinely avoided the topic of animism and even the term itself, instead revisiting this prevailing notion in light of their rich new ethnographies."

According to anthropologist Tim Ingold, animism shares similarities with totemism, but differs in its focus on individual spiritual beings who help perpetuate life, while totemism more typically holds that there is a primary source, such as the earth itself or the ancestors, which provide the basis of life. Certain indigenous religious groups such as the Australian Aborigines are more typically totemic, while others such as the Inuit are more typically animistic in their world view.

From his studies of child development, Jean Piaget suggested that children were born with an innate animistic worldview in which they anthropomorphized inanimate objects, and that it was later that they grew out of this belief. From her ethnographic research, Margaret Mead argued otherwise, believing that children were not born with an animistic worldview, but rather became acculturated to those beliefs as they were raised by their society. Stewart Guthrie saw animism, or "attribution" as he preferred it, as an evolutionary strategy to aid survival. He argued that both humans and other animal species view inanimate objects as potentially living as a means of constantly being on guard against possible threats.The explanation of his suggested, however, did not address the question of why such a belief it became central to religion.

In 2000, Guthrie suggested that the "more widespread" of animism was that it was the "attribution of spirits to natural phenomena such as stones and trees".

Animism today

Many anthropologists stopped using the term 'animism', considering it too close to early anthropological theory and religious polemics. However, the term had also been claimed by religious groups, namely communities indigenous and was nature worship - who felt it adequately described their own beliefs, and who in some cases actively identified themselves as "animists". It was adopted in this way by various scholars, however, they began to use the term in a different way, putting the focus on knowing how to behave around other people, some of whom are not human. As religious studies scholar Graham Harvey has stated, although the definition of "ancient animist" 3. 4; had been problematic, the term "animism" it was, however, "of considerable value as a critical scholarly term." for a religious and cultural style related to the world".

Animism is currently very popular in various regions of the world, since belief in the existence of the soul is something that occurs in the most dissimilar cultures throughout history and the world.

Animism is a fairly extensive subject and undoubtedly with a high degree of cultural personalization. Animism has always been related to try to explain what is beyond death, the existing intangible or simply the things that are inexplicable for the majority, that is, a way of thinking that links the human being with the things that surround.

The "new animism" arose largely from anthropologist Irving Hallowell's publications that were produced on the basis of his ethnographic research among Canada's Ojibwe communities in the mid-century XX. For the Ojibwe found by Hallowell, person did not require human resemblance, but humans were perceived as other people, including for example rock people and stone people. bear. For the Ojibwe, these people were voluntary beings who gained meaning and power through their interactions with others; by interacting respectfully with other people, they themselves learned to 'act like a person'. Hallowell's approach to understanding the Ojibwe personality differed greatly from earlier anthropological concepts of animism. to challenge modernist and Western perspectives of what a person is by entering into a dialogue with different world views.

Hallowell's approach influenced the work of anthropologist Nurit Bird-David, who produced a scholarly paper reassessing the idea of animism in 1999. Seven comments by other scholars were provided in the journal, discussing Bird-David's ideas. David.

More recently, postmodern anthropologists have become increasingly engaged with the concept of animism. Modernism is characterized by a Cartesian subject-object dualism that divides the subjective from the objective and culture from nature; From this point of view, animism is the inverse of scientism and is therefore inherently invalid. Drawing on the work of Bruno Latour, these anthropologists challenge these modernist assumptions and theorize that all societies continue to "encourage" the world around them, and not just as a Tylorian survival of primitive thinking. Rather, the characteristic instrumental reason of modernity is confined to our 'professional subcultures', allowing us to treat the world as a separate mechanical object in a delimited sphere of activity. We as animists also continue to create personal relationships with elements of the so-called objective world, be it pets, cars, or teddy bears, whom we recognize as subjects. As such, these entities are "approached as communicative subjects rather than inert objects perceived by modernists". These approaches are careful to avoid modernist assumptions that the environment consists dichotomously of a physical world other than humans., and of modernist conceptions of the person dualistically composed as body and soul.

Nurit Bird-David argues that "positivist ideas about the meaning of 'nature', 'life' and 'personality' they misdirected these previous attempts to understand local concepts. Classical theorists (it is argued) attributed their own modernist ideas of themselves to ' "primitive peoples" while they affirm that the "primitive peoples" they read their idea of themselves to others " She argues that animism is a" relational epistemology ", and not a failure of Tylor's primitive reasoning That is, self-identity among animists is based on their relationships with others, rather than on some distinctive characteristic of the self. Instead of focusing on the essentialized modernist self (the "individual"), people are seen as bundles of social relationships ("split"), some of which are with "superpeople" (i.e. not humans).

Guthrie expressed criticism of Bird-David's attitude towards animism, believing it promulgated the view that "the world is largely whatever our local imagination makes it out". This, he thought, would result in anthropology abandoning the "scientific project."

Tim Ingold, like Bird-David, argues that animists do not see themselves as separate from their environment:

"The hunters-gatherers, as a rule, do not approach their environment as an external world of nature that must be intellectually 'captured' and the separation of mind and nature does not take place in their thinking and practice. »

Willerslev extends the argument by noting that animists reject this Cartesian dualism, and that the animist identifies with the world, "feeling at the same time" inside "and" apart "from him so that the two slip incessantly in and out of each other in a closed circuit". The animist hunter is self-aware as a human hunter, but, through mimicry, can assume the point of view, senses, and sensitivity of its prey, in order to be one with it. Shamanism, from this point of view, is an everyday attempt to influence the spirits of ancestors and animals by mirroring their behaviors while the hunter makes his prey.

Ecologist and cultural philosopher David Abram articulates an intensely ethical and ecological understanding of animism grounded in the phenomenology of sensory experience. In his books & # 34; The Spell of the Sensuous & # 34; and "Becoming Animal", Abram suggests that material things are never completely passive in our direct perceptual experience, but actively perceived things "request our attention" or "call our focus," coaxing the perceiving body to continually engage with those things. In the absence of intervening technologies, he suggests, sensory experience is inherently animistic, revealing a material field that is animate and self-organizing from the start. Drawing on contemporary natural and cognitive science, as well as the perspective worldviews of diverse indigenous and oral cultures, Abram proposes a cosmology rich in pluralism and history in which matter is alive from beginning to end. Such a relational ontology is very much in accord, he suggests, with our spontaneous perceptual experience; it would bring us back to our senses and the primacy of the sensory terrain, by establishing a more respectful and ethical relationship with the more than human community of animals, plants, soils, mountains, waters, and weather patterns that sustain us materially.

In contrast to a long-standing trend in Western social sciences, which commonly provide rational explanations for animistic experience, Abram develops an animistic account of reason itself. He holds that civilized reason is sustained only by intense animistic involvement between human beings and their own written signs. For example, as soon as we turn our gaze to the alphabetic letters written on a page or screen, we 'see what they say', that is, the letters seem to speak to us, like spiders, trees, gushing rivers and lichen-encrusted rocks once spoke to our oral ancestors. For Abram, reading can usefully be understood as an intensely concentrated form of animism, one that effectively dwarfs all other older and more spontaneous forms of animistic participation in which we ever participated.

"To tell the story in this way, to provide an animist description of the reason, instead of the other way around, implies that animism is the broadest and most inclusive term, and that the modes of oral and mythical experience still underlie and support, all our literary and technological reflections. When the rooting of reflection in such modes of bodily and participative experience is totally unknown or unconscious, the reflexive reason becomes dysfunctional, involuntarily destroying the body and sensual world that sustains it. »

Religious studies scholar Graham Harvey defined animism as the belief "that the world is full of people, only some of whom are human, and that life is always lived in relationship with others" 34;. He added that he is therefore "concerned with learning to be a good person in respectful relationships with other people". Graham Harvey, in his 2013 Handbook of Contemporary Animism, identifies the perspective animist in line with the "I-you" of Martin Buber instead of the "I-he". In that sense, Harvey says, the Animist takes an I-you approach to relating to his world, where objects and animals are treated as a "you"; instead of an "it".

Animism beliefs

The general principle of animism is the belief in the existence of a substantial vital force present in all animated beings, and supports the interrelationship between the world of the living and that of the dead, recognizing the existence of multiple gods with whom that can be interacted with, or of a unique but inaccessible God in a modern adaptation. Its origins cannot be specified, unlike the prophetic religions, being together with shamanism one of the oldest beliefs of Humanity. The religion of Ancient Egypt was founded on animistic bases.

General characteristics

- Life continues after death.

- You can interact directly with spirits and nature.

- The existence of a wide variety of spirits, gods and entities is recognized.

- The soul can leave the body during meditation, trances, dreams or natural substances.

- It is believed in the mediation of sacred persons: shamans, sorcerers, sorcerers, mediums, etc.

- There are spiritual beings who live in the soul or spirit of the human being, or of any other being.

- Concepts are merged: individual-community, past-present-future, object-symbol, time-time, among other concepts.

- Atonement offerings or sacrifices are made at discretion.

- Everything is alive, the existence of a universal consciousness and universal connection.

- It is part of a whole being only one in all.

- Things are loaded with energy and affect the believer.

- The good and positive always prevails above all.

- Natural substances or plants are used as means of learning, healing, or revealing.

- It is always open to any new idea or thought.

- It all influences, but you decide.

- Respect, humility, knowledge, understanding and sharing.

Life after death

Most animistic belief systems hold that there is a soul that survives the death of the body. They believe that the soul passes into a more comfortable world, of abundant games and continuous agricultural crops. Other systems, such as that of the Navajo of North America, ensure that the soul remains on Earth as a ghost, sometimes evil.

Other cultures combine these two beliefs, stating that the soul must escape from this plane and not get lost on the way, otherwise it would become a ghost and wander for a long time. For success in this task, the survivors of the deceased consider it necessary to carry out mourning funerals and ancestor worship. In animistic cultures, rituals are sometimes not performed by individuals but by priests or shamans who are supposed to possess spiritual powers greater than or different from normal human experience.

The practice of head-shrinking practiced by some South American cultures stems from the animistic belief that an enemy's soul can escape if it is not trapped inside its skull. The enemy would then transmigrate into the womb of a female predatory animal, where she would be born to take revenge on the murderer. [citation required]

Animism and death

In many parts of the world it is held that the human body is the seat of more than one soul. On the island of Nías, four are distinguished: the shadow and the intelligence that die with the body, a tutelary spirit, and a second spirit that is carried on the head. Similar ideas are found among the Euahlayi of south-eastern Australia, the Dakotas, and many other tribes. Just as in Europe the ghost of a dead person usually haunts the cemetery or the place of death, other cultures assign different dwellings to the multiple souls that they attribute to man. Of the four souls of a Dakota, one stays with the corpse, another in the town, a third mixes with the air, while the fourth goes to the land of souls where the part it occupies may depend on its path in this life., their gender, manner of death or burial, in due observance of the burial ritual, or many other factors.

From the belief in the survival of the dead comes the practice of offering food, while lighting fires, etc., at the grave; at first, perhaps, as an act of friendship or filial piety, then as an act of worship towards the ancestor. The simple offering of food or bloodshed at the grave later evolves into a detailed sacrificial system. Even where ancestor worship does not exist, the desire to comfort the dead in the afterlife can lead to the sacrifice of wives, slaves, animals, etc. Thus, successively, until reaching the breaking or burning of objects in the grave, or the provision of the ferryman's toll: a coin placed over the mouth or eyes of the corpse to pay the expenses of the soul's journey. But everything does not end with the payment of the passage of the soul to the land of the dead. The soul can return to avenge his death by helping to discover the murderer, or to wreak vengeance on him. There is a widespread belief that those who suffer a violent death become evil spirits and endanger the lives of those who come near the haunted spot. The woman who dies in childbirth becomes a pontianak, and threatens the lives of human beings. People resort to magical or religious means to ward off their spiritual dangers.

Soul in inanimate objects

Some cultures make no distinction between animate and inanimate objects. Natural phenomena, geographic features, everyday objects, and manufactured items may also be endowed with souls and/or spiritual energy (prana, pneuma, qi, etc.) that would grant it a spiritual existence.

In northern Europe, ancient Greece, and China, the spirit of the water or river is the horse or a figure shaped like a bull. The snake-like water monster is more common, but it's not strictly a water spirit.

In Japan, the belief stands out in Tsukumogami, ordinary household items that have come to life on their hundredth birthday.

Syncretism is also manifested in this section of animism, changing the immanent spirit for the local god of recent times or the one that is in force. [citation required]

Animism and dreams

Dreams are sometimes narrated in towns as astral journeys made by the sleeper, or by animals or objects in their environment. Hallucinations, or lucid dreams, may have contributed to fortify this interpretation, as well as the animistic theory in general. Even more important than all these phenomena, since it is more regular and normal, was the daily period of sleep with its frequently irregular and incoherent ideas and images. The mere immobility of the body was enough to show that its state was not identical to that of wakefulness. When, moreover, the sleeper awoke to give an account of a series of visits to distant places, of which, as modern psychical investigations suggest, he could even throw out or bring back truthful details, the irresistible conclusion must have been that, in the dream, something that was not the body traveled to the afterlife.

If the phenomenon of dreams was of great importance in the prehistoric development of animism, this belief must have rapidly expanded into a philosophy of the nature of reality. From the reappearance in dreams of dead people, primitive man was inevitably led to the belief that there existed a disembodied part of man, a subtle body that survived the dissolution of the body. The soul was conceived to be a facsimile, a kind of double of the body, sometimes no less material, sometimes more subtle, sometimes totally impalpable and intangible.

Since not only human beings but also animals and inanimate objects are seen in dreams, the conclusion must have been that they too had spirits, although early religions may have reached this conclusion by another line of argument.

Evolution from animism to monotheism

Humanity, in its 150,000 years of having evolved Homo sapiens, saw beliefs in gods until about 30,000 years ago; being these polytheists. According to many scholars, monotheism evolved from polytheism only about 5,000 years ago.

Auguste Comte showed that the belief in monotheism had its evolution from polytheism and this in turn evolved from fetishism.

Religion and animism

Animism is often described as a religion. As interpreted by modern religions to try to make a difference, many animistic belief systems are not a religion at all, as religion involves some form of emotion. But in reality, animism is a philosophy that permeates multiple religions, that proposes an explanation of phenomena, that implies an attitude (and therefore a set of emotions) towards the cause of such phenomena.

However, the term is often used to describe an early stage of religion, in which people try to establish a relationship with invisible powers, conceived as spirits, and which can form various hierarchies, as in the multiple gods of polytheism.

There is ongoing disagreement (and no general consensus) as to whether animism is simply a singular, broadly encompassing religious belief, or a worldview in its own right, encompassing many diverse mythologies found throughout the world in many diverse cultures. This also raises controversy regarding the ethical claims that animism may or may not make: whether animism ignores questions of ethics altogether, or, by endowing various non-human elements of life with spirituality or personality nature, in fact promotes a complex ecological ethic. Two theories are known that suppose that animism was the origin of current religions. The first, called the ghost theory, relates the beginnings of human religions to the cult of the dead. It is primarily associated with the name Herbert Spencer, although it was also retained by Grant Allen.

The other theory, presented by Edward Burnett Tylor, maintains that the basis of all religion is animistic, but recognizes the non-human character of the gods of polytheism. Although the adoration of the ancestors or, more broadly speaking, the cult of the dead, in some cases overlapped with other cults or even made them disappear, its importance cannot be assured, rather the opposite (other cults ended up overlapping the ancestor worship). In most cases, the pantheon of gods is made up of a multitude of spirits, sometimes human, sometimes animal, with no sign of ever incarnating. The sun and moon gods, the fire, wind and water gods, the ocean gods, and above all the sky gods, show no sign of having been ghosts at any period of their history. It is true that some can be associated with ghost gods. For example, some natives of Australia do not say at any time that the gods are spirits, much less spirits of the dead; their gods are simply magnified wizards, super-men who never died. It can be said in general that ancestor worship and the cult of the dead never existed in Australia.

Fetishism / totemism

In many animistic worldviews, humans are often considered on an equal footing with other animals, plants, and natural forces.

Shamanism

A shaman is a person who is considered to have access to and influence in the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits, who usually enters a trance state during a ritual, and practices divination and healing. According to Mircea Eliade, shamanism encompasses The premise that shamans are intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds. Shamans are said to treat ailments/diseases by repairing the soul. Alleviating traumas affecting the soul/spirit restores the individual's physical body to balance and wholeness. The shaman also enters supernatural realms or dimensions to obtain solutions to problems affecting the community. Shamans can visit other worlds/dimensions to guide wrong souls and ameliorate human soul diseases caused by foreign elements. The shaman operates primarily within the spirit world, which in turn affects the human world. Restoration of balance results in removal of ailment.

However, Abram articulates a less supernatural and much more ecological understanding of the shaman's role than that proposed by Eliade. Drawing on his own field research in Indonesia, Nepal, and the Americas, Abram suggests that in animistic cultures, the shaman functions primarily as an intermediary between the human community and the more-than-human community of active agencies: local animals, plants and landforms (mountains, rivers, forests, winds, and weather patterns, all of which have their own specific sentience). Thus, the shaman's ability to heal individual instances of disease (or imbalance) within the human community is a by-product of his more ongoing practice of balancing reciprocity between the human community and the larger collective of animate beings in which he lives. that community is embedded.

Distinction from pantheism

Animism is not the same as pantheism, although the two are sometimes confused. Some religions are pantheistic and animistic. One of the main differences is that while animists believe that everything is spiritual in nature, they do not necessarily see the spiritual nature of everything that exists as united (monism), as pantheists do. As a result, animism places more emphasis on the uniqueness of each individual soul. In pantheism, everything shares the same spiritual essence, rather than having separate spirits or souls.

Animism in philosophy

The term "animism" it has been applied to many different philosophical systems. For example, to describe Aristotle's vision of the relationship between the soul and the body, also held by the Stoics and Scholastics. Leibniz's monadology has also been designated as animistic. The term has most commonly been applied to vitalism, a position primarily associated with Georg Ernst Stahl and revived by F. Bouillier (1813-1899), who held that life and mind are the guiding principles of evolution and growth, and that these did not originate in chemical or mechanical processes, but that there is a directing force that seems to guide the energy without altering its quantity. Another completely different class of ideas, also called animists, is the belief in the soul of the world, held by the Greek Plato, the German Schelling and the supporters of Gaia (the soul of the Earth).

Animism in anthropology

The vision of Edward Burnett Tylor

Edward Burnett Tylor argued that non-Western societies used animism to explain why things happened. Animism would thus be the oldest form of religion, which would explain why human beings developed religions to explain reality. At the time that Tylor presented his theories ( Primitive Culture , 1871), they were politically revolutionary.

Since the publication of Primitive Culture, however, Tylor's theories have been challenged from various angles:

- The beliefs of different peoples who live in different places of the globe and without communication among them cannot be incorporated as a single type of religion.

- The basic function of religion might not be the "explanation" of the universe. Critics like Marrett and Émile Durkheim argued that religious beliefs have emotional and social functions more than intellectuals.

- Tylor's theories are now seen as ethnocentric (centered in his own European race).

- His vision of religion (such as that which explains the inexplicable) was both contemporary and Western; and he was imposing it on non-Western cultures.

- It arbitrarily presents a progression that goes from religion (whose explanations about reality are subjective) to science (which provides explanations that satisfy certain groups) (See cultural evolution.)

Phenomena believed to have led to animism

Several researchers—including Edward Burnett Tylor, Herbert Spencer, Andrew Lang, and others—believed that the "savage" he began to believe in animism due to the contemplation of certain phenomena. A lively controversy ensued between the first two about the order of their respective lists of phenomena. Among these are trance, unconsciousness, illness, death, clairvoyance, dreams, apparitions of the dead, ghosts, hallucinations, echoes, shadows, and reflections.

Further reading

- Thomas, Northcote Whitbridge, "Animism," Encyclopædia Britannica1911.

Contenido relacionado

Ad hominem argument

Armenian diaspora

Aram (son of Hezron)