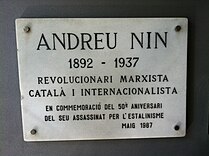

Andres Nin

Andrés Nin Pérez (Vendrell, February 4, 1892-Alcalá de Henares, June 22, 1937?), more commonly cited by his Catalan name Andreu Nin, was a Spanish politician, trade unionist and translator, known for his role in some Spanish leftist movements of the first third of the 20th century XX and, later, for his role in the Spanish civil war; Less known is his work as a good translator from Russian to Catalan of classics such as Ana Karénina , Crime and Punishment and some works by Anton Chekhov, among other works.

A teacher and journalist, during his youth he went through various political movements until joining the National Confederation of Labor (CNT), with an anarchist tendency. During his stay in Russia he witnessed the Russian revolution, a fact that would mark his conversion to Marxism. Upon his return to Spain, he would later become one of the founders of the small but active Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM). Over time he became a relevant figure of Spanish revolutionary Marxism in the first half of the 20th century. He disappeared during the course of the Spanish Civil War, after having been arrested by the Republican authorities as a result of the so-called "May Days".

Biography

Early Years

Born on February 4, 1892 in the Tarragona town of Vendrell, despite his modest origins —he was the son of a shoemaker and a peasant woman—, he managed, thanks to the efforts of his parents and his intelligence, to become a teacher and move to Barcelona shortly before the First World War. Although he taught for a time, in a secular and libertarian school, he soon dedicated himself to journalism and politics.

In 1911 he joined the ranks of the Catalan federalist movement, joining the Unió Federal Nacionalista Republicana, but the social conflict existing then made him evolve rapidly towards class approaches. The year 1917 was key to his life: events such as the August general strike, the Russian Revolution or the struggles between the Barcelona employers and the unions, especially the National Confederation of Labor (CNT), marked him deeply. Although he first joined the ranks of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), he soon embraced the cause of revolutionary syndicalism and joined the CNT, where after attending the second congress in 1919, he defended his entry into the Communist International and replaced as secretary of the National Committee to Evelio Boal, who had been assassinated. In November 1920, Nin himself would suffer an attack at the hands of the Free Unions that almost cost him his life.

Political activity

In the national plenary session of the CNT held in Lleida on April 28, 1921, he was chosen as one of the delegates that would be sent to Moscow to the Comintern congress and the founding congress of the Red Syndical International (Profintern) together Joaquín Maurín, Hilario Arlandis and Jesús Ibáñez; becoming a key figure in both internationals (the CNT had abandoned the Communist International in 1922). However, during his trip to Moscow he came to admire the Russian Revolution, after which he abandoned anarchism and became a communist. Nin, who would also attend the second Profintern congress, lived for a time in Moscow, at a time when the one who first worked for Nikolai Bukharin and later became the secretary of Leon Trotsky, one of the Bolshevik leaders during the revolution. Thanks to a job at the Profintern, Nin was able to visit France, Italy and Germany. In 1925 he received a visit in Moscow from the writer and journalist Josep Pla, whose trip was paid by the newspaper La Publicidad along with Eugenio Xammar and his wife. From 1926, he belonged to the so-called «Opposition of Left» led by Trotsky, who opposed the rise of Joseph Stalin within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, for which Nin had to leave the USSR in 1930. He came to master Russian and later produced important translations into Catalan, considered classic, of Russian novelists of the XIX century.

Second Republic

On his return to Spain after the proclamation of the Second Republic, Nin was instrumental in the formation of a Trotskyist (Bolshevik-Leninist) oriented group, the Spanish Communist Left (ICE), in May 1931. ICE it soon became a group affiliated with the International Left Opposition and went on to publish the newspaper The Soviet. However, although it had some very prominent militants, the Communist Left was too small a group to have real influence in Spanish political life. Although it was considered a Trotskyist party opposed to Stalin, from his exile in Norway Trotsky himself harshly criticized his political line.

Nin found herself in a very different country from the one she had left. In January 1933, he collaborated with the anarcho-syndicalist insurrection and was arrested in Valencia on January 20. The police took him to Madrid.

In 1934 he was part of the Alianza Obrera and intervened in the events of October 1934 in Catalonia. After the criticism received earlier for his political line, he ended up breaking with Trotsky after not accepting his claim to adopt an entrista tactic in the PSOE. When his group merged with Joaquín Maurín's Bloque Obrero y Campesino to found the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM) in 1935, Nin was appointed a member of the executive committee of the new party and director of its publication, La Nueva Era ; the following year he was elected general secretary of the POUM.

In May 1936 he was also elected general secretary of the Workers' Federation of Union Unity (FOUS), which had a strong union presence in the provinces of Lérida, Girona and also in Tarragona.

Spanish Civil War

After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Andrés Nin became the top leader of the POUM. Until July 1936 the party had had a very limited presence in the Catalan political arena and even less in the rest of Spain. However, from that moment on, Nin and other POUM leaders began to become known outside their traditional strongholds and used to speak in public. On August 2, in statements to the newspaper La Vanguardia, Nin stated:

The working class has solved the problem of the Church simply, leaving not even one standing.

After forming part of the Consell d'Economia de Catalunya between August and September 1936, on September 26 Nin was appointed Minister of Justice of the Generalitat. On October 14, 1936, he established the Popular Courts by decree. However, Nin's management as Minister of Justice was quite controversial. During those months, extrajudicial executions continued to take place, without Nin taking action on the matter. As the historian Hugh Thomas records, "Nin had not been characterized by humanitarian scruples regarding the "bourgeoisie"". The POUM militias also contributed to the repression of "fascists" and "enemies of the In the autumn, Nin had raised with the President of the Generalitat, Lluís Companys, the possibility of hosting Leon Trotsky as a refugee, who at that time had had to leave Norway due to Soviet pressure. This idea was not to the liking of the communists of the PSUC, who also participated in the government of the Generalitat. On November 24, the PSUC delivered to the CNT a proposal on the establishment of a new Generalitat government, which included the departure of Nin as Justice Counselor. Many anarchist members and leaders did not have much appreciation for Nin, whom they considered a renegade from the CNT, so they decided that it was more a conflict between Marxists. Andrés Nin continued to hold the position until December 16, when he was removed after the remodeling of the council. When explaining the reasons, According to what Nin later recounted during his interrogation, Josep Tarradellas also warned him of the danger that both the POUM and its leaders were running.

During the spring of 1937, the Republican police located an alleged letter written by Nin addressed to Francisco Franco, in which the Trotskyist leader would support an uprising plan by the fifth column in Madrid; the letter, actually a forgery made by the NKVD, was one of the main pieces of evidence indicting Nin. After the May Events, the communist campaign against the POUM intensified. Its leaders were openly accused of being fascists and conspiring with Franco. As early as May 28, communist pressure caused the authorities to suspend circulation of the party's newspaper, La Batalla.

On June 14, the General Director of Security, Colonel Antonio Ortega Gutiérrez, informed the Minister of Education and Health that the head of the NKVD in Spain, Alexander Orlov, had told him that all the leaders of the POUM should be arrested. The minister, who was the communist Jesús Hernández, went to speak directly with Orlov about this matter. The head of the NKVD alleged that there was evidence linking the Trotskyist party to Francoist espionage and that it was necessary for the government not to be aware of this plan because the interior minister, Julián Zugazagoitia, was a friend of some of the POUM leaders. On June 16, the Republican authorities closed the POUM headquarters in the Hotel Falcón and the party leadership was arrested by the police. According to the testimony of Julián Gorkin, the Republican police were accompanied by two foreigners, whom Gorkin suspected were agents of the Soviet secret service. Andrés Nin was separated from the rest of the party leadership, like Julián Gorkin and José Escuder, who was confined in prisons in Madrid and Barcelona. After being separated from the rest, Nin disappeared. The last POUM militant to see him alive was Teresa Carbó.

Controversy over his death

Nin was transferred to the city of Alcalá de Henares, near Madrid; the chosen place had become an important base for the Soviets in republican Spain, for which reason it offered security guarantees. detention. Hugh Thomas points out that Nin was taken by car from Barcelona and then taken to the Cathedral of Alcalá de Henares, which functioned as a private prison for the Soviet NKVD Some maintain that he died in Alcalá de Henares. However, various circumstances surrounding his death, such as whether or not he was subjected to torture before his execution, remain to be clarified. According to Paul Preston, Nin was possibly killed on June 22 by skinning, by order of Orlov and with the help of Iosif Grigulevich. There is little doubt that the order for Nin's execution came from Moscow. For his part, Thomas claims that he may have been murdered in El Pardo park, near Madrid, but the final destination of his remains remains a mystery.. Nin's biographer, Francesc Bonamusa, would comment on this:

However, the fundamental aspects of the kidnapping and consequent murder of Andrés Nin are evident. Nin was arrested by members of the police services in Madrid and Barcelona, and not by policemen from Valencia, who was the seat of the government of the Republic. He was transferred first to Valencia and later to Madrid... once in Madrid, he was surely transferred to the contraspionage services of the NKVD, and transferred to one of his barracks in Alcalá de Henares or El Pardo. For these reasons, and since Nin was not a government official, it was impossible for the Ministers of Justice, Manuel de Irujo, and of Government, Julián Zugazagoitia, to obtain information about the whereabouts of the former Minister of Justice of the Generality.

A few days after his arrest, rumors began to spread in Republican Spain that Andrés Nin had been assassinated. A campaign spread with the slogan: "Where is Nin?" The former Minister of Health, the anarchist Federica Montseny, was one of the first personalities to raise the issue in public. sure of what had happened: several socialist ministers asked the two communist ministers, who claimed to be unaware of everything related to this matter. The semi-official version that began to circulate was that Nin had been freed from the checa by "his friends from the Gestapo". This was stated by Juan Negrín, head of the Government of the Republic. Salamanca or Berlin" to the question about the true whereabouts of the Trotskyist leader. According to Ricardo Miralles and Hugh Thomas, Negrín would have been aware of the truth about what happened from the beginning despite echoing the implausible version of the Gestapo; Thomas adds that the Nin case was actually a "dirty business", but that the republican leaders decided that it was better not to bother the Soviets in order to continue receiving the precious military aid. On the other hand, the republican leaders and ministers did not feel a special appreciation for the leader of this small party, which they considered a mere "group of agitators that was harming the war effort." Julián Zugazagoitia, however, commented that this action had been carried out without the knowledge and/or consent of the Republican government. Also Manuel Azaña, see, for example, the entry in his Diary corresponding to October 18, 1937.

Works

- Les dictadures dels nostres dies (1930)

- Els moviments d'emancipació nacional (1935)

- The Spanish Revolution. (1930-1937)Pelai Pagès (2007)

- Les anarchistes et le mouvement syndical (1924)

- The Spanish proletariat before the Revolution (1931).

Translations from Russian

- 1929: Crim i càstig of Fiódor Dostoievski

- 1929: History of Russian Culture of Mikhail Pokrovski

- 1929: My Expertises in Spain of Lev Trotski

- 1931: Stepàntxikovo i els seus habitants of Fiódor Dostoievski

- 1931: Intimate letters of Lenin

- 1931: The Volga flows into the Caspian Sea of Boris Pilniak

- 1931: The Russian Revolution of Mikhail Pokrovski

- 1931: History of the Russian Revolution (The February Revolution) of Lev Trotski

- 1932: Russian literature of the revolutionary era of Vyacheslav Polonski

- 1932: History of the Russian Revolution (The October Revolution) of Lev Trotski

- 1932: The Sexual Life of Contemporary Youth of I. Helman

- 1935: The first noia: història romàntica of Nikolai Bogdanov

- 1935: What has passat? of Lev Trotski

- 1935: Bakunin of Vyacheslav Polonski

- 1935: Anna Karénina of Lev Tolstói

- 1936: A waterfall of Antón Chéjov

- 1936: Prou compassió! of Mikhail Zóschenko

- 1974: Infància, adolescència i youngtut of Lev Tolstói

- 1976: The Permanent Revolution of Lev Trotski

- 1982: L'Estepa i altres narracions of Anton Chéjov

Translations from French

- 1935: L'insurgent Jules Vallès.

Contenido relacionado

Rodrigo de Cervantes

Tartessian language

Philippine Academy of the Spanish Language