Andalusia

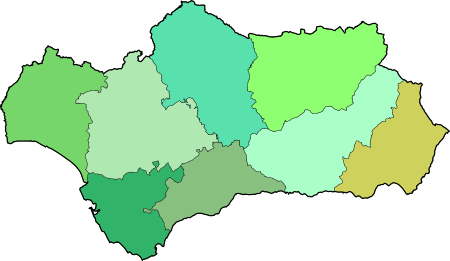

Andalusia is a Spanish autonomous community recognized as a historical nationality by its Statute of Autonomy, made up of eight provinces: Almería, Cádiz, Córdoba, Granada, Huelva, Jaén, Málaga and Seville. Its capital and most populated city is Seville, seat of the Government Council of the Junta de Andalucía, the Parliament and the Presidency of the Junta de Andalucía. The headquarters of the Superior Court of Justice of Andalusia is located in Granada.

It is the most populous autonomous community in the country (8,476,718 inhabitants in 2021) and the second largest (87,268 km²) —after Castile and Lion-. It is located in the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula; bordering to the west with Portugal, to the north with the autonomous communities of Extremadura (Badajoz) and Castilla-La Mancha (Ciudad Real) and (Albacete), to the east with the Region of Murcia, to the southwest with the Atlantic Ocean and to the south with the Mediterranean Sea and Gibraltar. Through the Strait of Gibraltar, separated by 14 km at its narrowest, are Morocco and Ceuta on the African continent. In 1981 it became an autonomous community, under the provisions of the second article of the Spanish Constitution of 1978, which recognizes and guarantees the right to autonomy of Spanish nationalities and regions. The process of political autonomy was carried out through the restrictive procedure expressed in article 151 of the Constitution, after the mass demonstrations of December 4, 1977 and the referendum of February 28, 1980, where the Andalusian people expressed their desire to position themselves at the forefront of the aspirations for self-government at the highest level in all the peoples of Spain. Andalusia was therefore the only Community that had a specific source of legitimacy in its path of access to autonomy expressed at the ballot box by means of a referendum. In the preamble of the Andalusian Statute of Autonomy of 2007 it is stated verbatim that:

The Andalusian Manifesto of Cordoba described Andalusia as a national reality in 1919, whose spirit the Andalusians fully seized through the process of self-government reflected in our Magna Carta. In 1978 the Andalusians gave broad support to the constitutional consensus. Today, the Constitution, in its article 2, recognizes Andalusia as a nationality within the framework of the indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation.

In the articles of the autonomous statute, Andalusia is granted the status of "historical nationality", reflecting the political identity of the Andalusian people as a result of its historical and cultural singularity. In the previous statute, the Autonomy Statute of 1981 or the Carmona Statute, it was defined as "nationality".

The geographical framework is one of the elements that gives Andalusia its own uniqueness and personality. From a geographical point of view, three large environmental areas can be distinguished, formed by the interaction of the different physical factors that affect the natural environment: Sierra Morena —which separates Andalusia from the Meseta—, the Betic systems and the Betic depression that individualize Upper Andalusia from Lower Andalusia.

The history of Andalusia is the result of a complex process in which different cultures and peoples merge over time, such as the Iberian, the Phoenician, the Carthaginian, the Roman, the Byzantine, the Andalusian, the Sephardic, Gypsy and Spanish, which have given rise to the formation of Andalusian identity and culture.

Currently, the Andalusian economy is marked by the region's disadvantage with respect to the Spanish and European global frameworks due to the late arrival of the industrial revolution, further hampered by the peripheral situation that Andalusia adopted in the international economic circuits. This resulted in a lower impact of the industrial sector on the economy, a great relative weight of agriculture and a hypertrophy of the service sector.

Toponymy

The place name «Andalucía» was introduced into the Spanish language during the XIII century under the form «el Andalucía». It is the Castilianization of al-Andalusiya, a name and Arabic adjective referring to al-Andalus, a name given to the territories of the Iberian Peninsula under Islamic rule since 711 to 1492. Several etymologies have been proposed for this place name. The so-called vandala thesis derives al-Ándalus from Vandalia or Vandalusia (land of the Vandals) and although it was widespread from the XVI century onwards, it currently does not enjoy any scientific credibility. The so-called Visigothic thesis finds its etymological origin in the Visigothic name of the ancient Roman province of Bética: *Landahlauts. The Visigoths, upon occupying these lands, divided them up by lottery; the prizes that fell to each one of them and the corresponding lands were called sortes Gothica, appearing in the written sources, all in Latin, as Gothica sors (singular) as designation of the Gothic kingdom as a whole. The corresponding Gothic designation, *Landahlauts ("land of lottery"), would be transformed according to this thesis into al-Andalus. A third thesis, the Atlantic thesis explains the appearance of the place name al-Andalus as a corruption of the Latin Atlanticum. Several sources such as the English Encyclopedia and scholars such as Dietrich Schwanitz and Heinz Halm, reaffirm theories of a place name formed even before the Arab occupation.

Regarding its use, the word "Andalusia" has not always exactly referred to the territory known today as such. During the last phases of the Christian Reconquest, this name was granted exclusively to the south of the peninsula under Muslim rule, later remaining as the name of the last territory to be reconquered. In the First General Chronicle of Alfonso X the Wise, written in the second half of the XIII century, the term Andalusia is used in three different meanings:

- As a simple translation of al-Andalus. The name of al-Ándalus already appears in Arabic traditions and poetry of the first era of Islam before the conquest. It appears in these eastern sources and in the first ones that narrate the conquest of Hispania as the name of an island, Chazirat al-Andalus, or of a sea, Bahr al-Andalus.

- To designate the territories conquered by Christians in the Guadalquivir valley and in the kingdoms of Granada and Murcia. In fact Alfonso X was titled King of Castile, Lion and all of Andalusia in a 1253 document.

- To name the lands conquered by Christians in the Guadalquivir valley (Reinos de Jaén, Córdoba and Seville). This third meaning would be the most common during the Lower Middle Ages and the Modern Ages. From the administrative point of view, the kingdom of Granada maintained its name and singularity within the Andalusian context, due, above all, to its emblematic character as the culmination of the Reconquista and to being the headquarters of the important Real Chancillería de Granada. However, the fact that the conquest and repopulation of the kingdom was made mostly by Andalusians, made during the Modern Age the notion of Andalusia extend, in fact, to the whole of the four kingdoms, often called the "four kingdoms of Andalusia", at least since the mid-centuryXVIII.

Sometimes and unofficially this territory has been called "Castilla la Novísima" following the chronological order of the Reconquest, after Castilla la Vieja and Castilla la Nueva.

Symbols

Shield

The coat of arms of Andalusia shows the figure of a young Hercules between the two Pillars of Hercules that tradition places in the Strait of Gibraltar, with an inscription at the foot of a legend that says: «Andalusia itself, for Spain and Humanity", on the background of an Andalusian flag. The two columns are closed by a semicircular arch with the Latin words Dominator Hercules Fundator, also on the background of the Andalusian flag.

Flag

The official flag of Andalusia is made up of three horizontal bands green, white and green, of equal size; His shield is located on the central white band. It was created by Blas Infante and approved in the Ronda Assembly of 1918. Infante chose green as a symbol of hope and union and white as a symbol of peace and dialogue. The choice of these colors is due to the fact that Blas Infante considered that they had been the most used throughout the history of the Andalusian territory. According to him, the banner of the Andalusian Umayyad dynasty was green and represented the call of the people. White, on the other hand, symbolized forgiveness among the Almohads, which in European heraldry is interpreted as parliament or peace. Other historical news justify the choice of the colors of the flag. Andalusian nationalists call it the Arbonaida, which means “white and green” in the Mozarabic language.

Anthem

The Andalusian anthem is a musical composition by José del Castillo Díaz, director of the Seville Municipal Band and commonly known as Maestro Castillo with lyrics by Blas Infante. The music is inspired by Santo Dios, a popular religious song that peasants and day laborers from some Andalusian regions sang during the harvest in the provinces of Malaga, Seville and Huelva.[ citation required] Blas Infante reported this song to Maestro Castillo, who adapted and harmonized the melody. The lyrics of the anthem appeal to the Andalusians to mobilize and ask for "land and freedom", through a process of agrarian reform and a statute of political autonomy for Andalusia, within the framework of Spain.

The Andalusian Parliament unanimously approved in 1983 that, in the preamble of the Statute of Autonomy for Andalusia, Blas Infante be recognized as "Father of the Andalusian Homeland", recognition that was revalidated in the reform of said statute, submitted popular referendum on February 18, 2007.

Official day

Andalusia Day is celebrated on February 28 and commemorates the 1980 referendum, which gave full autonomy to the Andalusian community after a long struggle through the procedure stipulated in article 151 of the Constitution for those communities that, like the Andalusian, they had not approved a statute of autonomy during the Second Republic due to the outbreak of the Civil War.

The honorary title of Favorite Son of Andalusia is granted by the Junta de Andalucía to those who recognize exceptional merits that have redounded to the benefit of Andalusia, for their work or scientific, social or political actions. It is the highest distinction of the autonomous community.

Geography

One of the elements that gives Andalusia its uniqueness and personality is its geographical setting. The Sevillian historian Domínguez Ortiz summarizes this condition stating that:

[...] we must seek the essence of Andalusia in its geographical reality, on the one hand and, on the other, in the consciousness of its inhabitants. From a geographical point of view, the whole of the southern lands is too broad and varied to encompass all in one unit. In reality there are not two, but three Andalusias: the Sierra Morena, the Valley and the Penibbean [...]

These three large environmental units are going to be the result of the conjunction of different physical factors, where relief plays a fundamental role.

Limits

Andalusia covers an area of 87,268 km², which is equivalent to 17.3% of the Spanish territory, making it comparable with many European countries, both for its surface area and for its internal complexity. To the east and west it borders the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean and Portugal respectively, while to the north it does so with the Sierra Morena, which separates it from the Meseta, and to the south with the Strait of Gibraltar, which separates it from the African continent.

Andalusia is located at a latitude between 36º and 38º44' N, in the temperate-warm zone of the Earth, giving its climate very defining characteristics such as the bonanza of its temperatures and the dryness of its summers. However, in the broad framework defined by its limits there are some great internal contrasts. In this way, it goes from the extensive coastal plains of the Guadalquivir River —at sea level— to the highest areas of the peninsula in the Sierra Nevada. The dryness of the Tabernas desert contrasts with the natural park of the Sierra de Grazalema, the rainiest in Spain. More significant, if possible, is the transit from the snowy peaks of Mulhacén to the subtropical coast of Granada, just 50 km away.

Climate

Andalusia falls entirely within the Mediterranean climatic domain, characterized by the predominance of high summer pressures —Azores anticyclone—, which result in the typical summer drought, broken at times with torrential rainfall and torrid temperatures. In winter, the tropical anticyclones move to the south and allow the polar front to penetrate the Andalusian territory. The instability increases and rainfall is concentrated in the autumn, winter and spring periods. The temperatures are very mild.

Nevertheless, there is a great diversity of climatic types in the different areas of Andalusia, causing great richness and landscape contrasts that are increased by the arrangement of the orogens and their location between two masses of water with very different characteristics.

Precipitation decreases from west to east, with the rainiest point being the Sierra de Grazalema (with the maximum historical annual rainfall recorded in the entire Iberian Peninsula and Spain, in 1963: 4346 mm) and the least rainy from continental Europe (Cabo de Gata, 117 mm per year). The "humid Andalusia" coincides with the highest points of the community, especially the area of the Serranía de Ronda and the Sierra de Grazalema. The Guadalquivir valley presents average rainfall. In the province of Almería is the Tabernas desert, the only desert in Europe. The rainy days a year are around 75, descending to 50 in the most arid areas. Thus, in a large part of Andalusia, there are more than 300 days of sunshine a year, with Malaga and Almería being the Spanish cities with the most hours of light, an average of 8.54 per day, according to data from the INE (National Statistics Institute). which in 2017, accumulated 3820 hours of sunshine in both.

The average annual temperature in Andalusia is above 16 °C, with urban values ranging between 18.5 °C in Malaga and 15.1 °C in Baeza. In a large part of the Guadalquivir valley and the Mediterranean coast, the average is around 18°. The coldest month is January (6.4 °C on average in Granada) and the hottest months are July or August (28.5 °C on average), with Córdoba being the hottest capital followed by Seville.

The highest temperatures in Spain, the peninsula and Europe are recorded in the Guadalquivir valley, with an all-time high of 46.9 °C in Córdoba and 46.8 °C in El Granado (Huelva). according to AEMET. Montoro registered the maximum temperature of 47.3 °C on July 13, 2017. Although there are data from previous records, they are very doubtful because they were measured with inadequate instruments. The mountains of Granada and Jaén are those that register the lowest temperatures in the entire south of the Iberian Peninsula. In the cold wave of January 2005, -21 °C was reached in Santiago de la Espada (Jaén) and -18 °C in Pradollano (Granada). Sierra Nevada has the lowest average annual temperature in the south of the peninsula (3.9 °C in Pradollano) and its peaks remain snow covered most of the year.

Relief

The relief is one of the main factors that configures the natural environment. The mountainous alignments and their layout have a special impact on the configuration of the climate, the fluvial network, the soils and their erosion, the bioclimatic floors and will even have an influence on the way natural resources are used.

The Andalusian relief is characterized by the strong altitudinal and slope contrast. Between its borders are the highest levels of the Iberian Peninsula and almost 15% of the territory above 1000 m; in front of the depressed zones, with less than 100 msnm of altitude in the great Bética Depression. On slopes, the same phenomenon occurs.

As for the Andalusian coasts, the Atlantic coast is characterized by an overwhelming predominance of beaches and low coasts; For its part, the Mediterranean coast has a very important presence of cliffs, especially in the Axarquía of Malaga, Granada and Almería.

The asymmetric character is such that it will configure a natural division between Upper and Lower Andalusia following the main relief units:

- Sierra Morena, (with the Bañuela peak of 1323 m) at the same time that marks a break between Andalusia and the Meseta, presents a great separation — increased by its depopulation — between the Sierra and the Campiña de Huelva, Seville, Córdoba and Jaén. However, its elevation is scarce and only Sierra Madrona manages to overcome 1300 m. n. m. at its highest point the Bañuela (out of Andalusia). Among this mountainous system is the desfiladero de Despeñaperros, which constitutes the natural border with Castilla.

- The Béticas (Penibética y Subbética) ranges parallel to the Mediterranean and are not aligned, leaving among them the Intrabetic Surco. The Subbetic is very discontinuous, so it presents numerous corridors that facilitate communication. On the contrary, the Penibbean has an isolated barrier between the Mediterranean and the interior. The highest heights of Andalusia are in Sierra Nevada, in the province of Granada; there are the highest peaks of the Iberian peninsula: the Mulhacén peak (3478 m) and the Veleta (3392 m).

- Bética Depression is between both systems. It is a plain territory almost entirely, open to the Gulf of Cadiz in the southwest. Throughout history, this has been the main population of Andalusia.

Hydrography

Atlantic and Mediterranean rivers flow through Andalusia. The Guadiana, Piedras, Odiel, Tinto, Guadalquivir, Guadalete and Barbate rivers belong to the Atlantic slope; while the Guadiaro, Guadalhorce, Guadalmedina, Guadalfeo, Andarax (or Almería river) and Almanzora correspond to the Mediterranean slope. Among them, the Guadalquivir stands out for being the longest river in Andalusia and the fifth in the Iberian Peninsula (657 km).

The rivers of the Atlantic basin are characterized by being extensive, flowing for the most part through flat terrain and irrigating extensive valleys. This character determines the estuaries and marshes that form at their mouths, such as the Doñana marshes formed by the Guadalquivir river and the Odiel marshes. The rivers of the Mediterranean basin are shorter, more seasonal and with a steeper average slope, which causes less extensive estuaries and valleys less prone to agriculture. The leeward effect caused by the Betic Systems means that their contributions are reduced.

The Andalusian rivers fall into five different hydrographic basins: the Guadalquivir basin, the Andalusian Atlantic basin, which includes the sub-basins of Guadalete-Barbate and Tinto-Odiel, and the Guadiana basin, which would make up the Atlantic slope. In the Andalusian Mediterranean basin are the rivers that flow into the Mediterranean. In addition, a small part of the Segura river basin extends in Andalusia.

Floor

Pedogenesis is a synthetic process in which the rest of the natural factors, both biotic and abiotic, intervene. Therefore, it is not surprising that, according to the predominant type of soil, Andalusia can be divided into three large landscape units.

In Sierra Morena, due to its morphology and its acid soils, mainly shallow and poor soils with forest vocation are developed. In the valleys and in limestone areas, deeper soils are found where there is poor cereal agriculture normally associated with cattle raising. Something similar occurs in the Betic Systems. Its morphostructural complexity makes it the area with the most heterogeneous soil and landscape in Andalusia. In very broad terms, it should be noted -as a difference with the other great montane space of Andalusia- the existence of a predominance of basic materials in the Subbético, which together with the ridged morphology, generate deeper soils with greater agronomic capacity, mainly used in the cultivation of olive groves. Finally, we must highlight the Depresión Bética and the Surco Intrabético, as the main spaces for the development of deep, rich soils with great agronomic capacity. It is necessary to differentiate the alluvial soils with a loamy texture and especially suitable for intensive irrigated crops, where those of the Guadalquivir valley and the plain of Granada stand out.

For its part, in the undulating areas of the countryside, there is a double dynamic: in the troughs —filled with older limestone materials— where very deep clayey soils have developed, called bujeo soils or Andalusian black lands where dryland arable crops are typical. In the hilly areas, another very typical soil has been developed —albariza— with very favorable conditions for growing vines.

The poorly consolidated sandy soils —mainly on the Huelva and Almeria coasts—, despite their marginality, in recent decades have taken on great relevance thanks to the forced cultivation under plastic of vegetables and berries —strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, among others-.

Flora

Andalusia, biogeographically speaking, is part of the Holarctic Kingdom, specifically of the Mediterranean Region, Western Mediterranean subregion and is made up of five phytogeographical sectors: the Marianico-Monchiquense sector, the Cadiz-Aljíbico and Onubense sector, the Béticos sectors, the Almeria sector and the Manchego sector. These sectors belong to as many Iberian chorological provinces or sub-provinces.

In general terms, the typical vegetation of Andalusia is the Mediterranean forest, characterized by evergreen and xerophytic vegetation, adapted throughout the summer period of drought. The climactic and dominant species is the holm oak, although there are abundant cork oaks, pines, Spanish firs, among others, and of course the olive and almond trees as cultivated species. The dominant understory is made up of thorny and aromatic woody species: species such as rosemary, thyme and cistus are very typical of Andalusia. In the most humid areas and with acid soils, the most abundant species are oak and cork oak, and eucalyptus stands out as a cultivated species. In this context is the greatest mycological biodiversity in Europe. There are also abundant gallery forests of leafy species: poplars and elms, and even poplar as a cultivated species in the Granada plain.

Wildlife

The existing biodiversity in Andalusia extends to the fauna. In this way, more than 400 species of vertebrates of the 630 existing in Spain inhabit this autonomous community. Its strategic position between the Mediterranean basin, the Atlantic Ocean and the Strait of Gibraltar makes Andalusia one of the natural passageways for thousands of migratory birds that travel between Europe and Africa. Andalusian wetlands are home to a very rich birdlife, for the combination of species of African origin, such as the horned coot, purple swine or flamingo, with birds from northern Europe, such as geese. Among the birds of prey, the imperial eagle, the griffon vulture and the kite stand out.

As for herbivores, there are deer, fallow deer, roe deer, mouflon and ibex, the latter in decline compared to the heron, an invasive species introduced from Africa for hunting purposes in the 1970s. Among the small herbivores The hare and the rabbit stand out, which constitute the basis of the diet of most of the carnivorous species of the Mediterranean forest.

Large carnivores such as the Iberian wolf and the Iberian lynx are highly threatened and are limited to Doñana, Sierra Morena and Despeñaperros. The wild boar, on the other hand, is well preserved due to its hunting importance. Smaller carnivores, such as otter, are more abundant and in different conservation situations, while foxes, badgers, polecats, weasels, wildcats, genets, and mongoose are more abundant.

Other noteworthy species are the ocellated lizard, the snouted viper and the Aphanius baeticus or Andalusian salinete, the latter highly threatened.

Invasive Species

According to the Catalog of Species included in the Andalusian Program for the Control of Invasive Alien Species, in Andalusia there are a large number of both animal and plant species that have been introduced into the Andalusian ecosystem. Among them, the invasive species are the most dangerous for the conservation of the biodiversity of Andalusian ecosystems.

Invasive species that manage to adapt to the new environment become strong in it and even decimate the population of native species. These exotic species can reach the new environment in various ways: abandonment of pets in the new ecosystem, destruction by man of their previous ecosystem, implantation by man in the new ecosystem to alleviate a problem... The reasons are diverse., but the solutions are similar in all cases, since what is being attempted is to progressively reduce the population of the invasive species.

In Andalusia, invasive species are both animal and plant, for example:

- Uña de cat: it is distributed on the coasts of western Andalusia (Huelva and Cadiz above all). It was introduced for decorative use and for the fixing of dunes and taludes on the coast. It promotes the displacement of species of coastal dunes, the decrease in the incident light in the soil and the germination of natives and is competition for native species in pollination.

- Eucalyptus: it is spread throughout the Andalusian territory as it was introduced for forest purposes and for soil fixing. It mainly causes the reduction of plant cover and the displacement of indigenous plants, overexploitation of aquifers.

- Chumbera: spread throughout the community, especially on the coastline. It was introduced with ornamental use and formation of hedges. As a secondary use it has also been given the forage plant for livestock and fruit producers for human consumption. It is a plant that invades coastal ecosystems of interest (Dunar systems, forests and coastal bushes) in which it competes with native flora species.

- American river crab: it is distributed throughout the Andalusian territory. It was the fishermen who introduced it into voluntary releases for fishing. It has many negative effects on native flora and fauna through predation. It even comes to compete with native species of other crabs for their larger size, for their reproductive rate and for their resistance to pests. Its main impact is to be the vector of the fungus Aphanomices astaci, which produces afanomicosis and which is fatal for the native crab (Austropotamobius pallipes). They also dig galleries that increase the erosion of the riverbanks.

- Common tent: it is present in rivers of all Andalusia. It is very abundant in the reservoirs and in the middle and lower sections of the rivers with the most flowing. It was voluntarily introduced by fishermen for sport fishing. The common tent is causing serious ecological imbalances. It is related to an increase in the turbidity of the water foil due to its movements and its excrements. The increase in turbidity is responsible for a lower penetration of sunlight and consequently for the disappearance of submerged macrophytes, indirectly affecting invertebrates and aquatic birds.

- Florida Galapague: was introduced in Spain in the 1980s. In Andalusia it is distributed by different coastal wetlands, although it can also be found in lakes and ponds like those of the peri-urban parks. Its introduction was due to the voluntary or involuntary release of animals raised as pets. It is a voracious predator of invertebrates, fish and amphibians as well as floating and sesile aquatic vegetation. It competes with other species of Galapagos to which it moves as the case of the European Galapagos. It has adapted very well to the medium as it is able to live in natural conditions that other species of Galapagos do not tolerate (greater pollution and human presence).

- Cotorra de Kramer: arrived in Spain in the mid-1980s and has spread through parks and gardens of Almeria, Granada, Malaga and Seville. Like other exotic birds, their introduction into the Andalusian ecosystem came from the involuntary release of pet-breededed animals. It is a great competition for nests with bats and woodpecker birds (Picidae). It is competition in the trophic chain with the common mile, the capirotada curl and other granivores and frugivores.

- Micropterus salmoides: commonly known as black bass.

Natural spaces

Andalusia has a large number of natural spaces and ecosystems of great singularity and environmental value. Its importance and the need to make the conservation of its values and its economic use compatible, have promoted the protection and management of the most representative landscapes and ecosystems of the Andalusian territory.

The different protection figures are included within the Network of Protected Natural Spaces of Andalusia (RENPA) that integrates the natural spaces located in the Andalusian territory protected by some regulation at the regional, national, community level or international agreements. The RENPA is made up of 150 protected spaces divided into 3 National Parks, 23 Natural Parks, 21 Peri-Urban Parks, 32 Natural Areas, 2 Protected Landscapes, 37 Natural Monuments, 28 Natural Reserves and 4 Concerted Natural Reserves, all of them included in the Nature Network. 2000 at a European level. At the international level, it is worth highlighting the 9 Biosphere Reserves, 20 Ramsar Sites, 4 Specially Protected Areas of Mediterranean Importance -ZEPIM- and 2 Geoparks.

In total, practically 20% of the Andalusian territory is under the protection of some regulation in the different areas, which represents approximately 30% of the protected territory in Spain. Among the many spaces, the Sierra Natural Park stands out from Cazorla, Segura and Las Villas, the largest natural park in Spain and the second in Europe, the Sierra Nevada National Park, Doñana and the sub-desert areas of the Tabernas Desert and the Cabo de Gata-Níjar Natural Park.

History

The idea of unifying the provinces of southern Spain under the same administrative region was born in the second half of the XIX century The Andalusian movement gained more relevance during the reign of Alfonso XIII and the second Spanish Republic, and having Blas Infante as the greatest exponent of said movement. During the period of the Second Republic, an attempt was made to establish Andalusia as an autonomous region. To this end, the Assembly of Córdoba in 1933 was held, in which delegations from the eight provinces involved (Huelva Province, Seville Province, Cádiz Province, Córdoba Province, Jaén Province, Málaga Province, Granada Province and Province of Almería) met to discuss the elaboration of an autonomy statute. The assembly ended with the withdrawal of the delegations from Huelva, Jaén, Granada and Almería, and the abstention of the delegation from Malaga. The failure of the Córdoba assembly, together with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War and the subsequent victory of the national side, led to the idea of constituting Andalusia as an autonomous region being temporarily set aside. It would not be until 1981 when, after the referendum on the initiative of the autonomous process of Andalusia in 1980, Andalusia would obtain autonomy. However, it is also relevant to briefly expose the previous history of the territory currently integrated into said historical nationality.

The geostrategic position of Andalusia in the extreme south of Europe, between it and Africa, between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, as well as its mineral and agricultural wealth and its large surface area of 87,597 km² (greater than many of the countries Europeans), form a combination of factors that made Andalusia a focus of attraction for other civilizations since the beginning of the Metal Age.

In fact, its geographical situation as a link between Africa and Europe, makes some theories point to the fact that the first European hominids, after crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, were located in Andalusian territory. The first cultures developed in Andalusia (Los Millares, El Argar and Tartessos) had a clear oriental tinge, due to the fact that peoples from the eastern Mediterranean settled on the Andalusian coast in search of minerals and left their civilizing influence. The process of passing from prehistory to history, known as protohistory, was linked to the influence of these peoples, mainly Greeks and Phoenicians, a broad historical moment in which Cádiz was founded, the oldest city in Western Europe, followed in antiquity through another Andalusian city: Malaga.

Andalusia was fully incorporated into the Roman Empire with its conquest and Romanization, creating the province of Bética, a subdivision of a primitive province that dates from the Roman conquest called Hispania Ulterior. Given its status as a senatorial province due to its very high degree of Romanization, it was the only province in Hispania to hold this status, it had great economic and political importance in the Empire, to which it contributed numerous magistrates and senators, in addition to the outstanding figures of the Emperors Trajan and Hadrian.

The Germanic invasions of the Vandals and later of the Visigoths did not make the cultural and political role of Baetica disappear and for centuries V and VI the Betico-Roman landowners practically maintained independence from Toledo. Figures such as San Isidoro de Sevilla or San Hermenegildo stood out in this period.

In 711 there was an important cultural break with the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. The Andalusian territory was the main political center of the different Muslim states of al-Andalus, with Córdoba being the capital and one of the main cultural and economic centers of the world at that time. This period of flourishing culminated with the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba, where figures such as Abderramán III or Alhakén II stood out. Already in the XI century there was a period of serious crisis that was taken advantage of by the Christian kingdoms of the north of the peninsula to advance their conquests and by the different North African empires that followed one another —Almoravids and Almohads— that exerted their influence in al-Andalus and also established their centers of power on the peninsula in Granada and Seville, respectively. Between these periods of centralization of power, the political fragmentation of the peninsular territory occurred, which was divided into first, second and third kingdoms of taifas. Among the latter, the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada played a fundamental historical and emblematic role.

The Crown of Castile gradually conquered the territories in the south of the peninsula. Fernando III personalized the conquest of the entire Guadalquivir valley in the XIII century. The Andalusian territory was divided into a Christian part and a Muslim part until in 1492 the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula ended with the capture of Granada and the disappearance of the homonymous kingdom.

It was in the XVI century when Andalusia further exploited its geographical position, as it centralized trade with the New World, through the Casa de Contratación de Indias, based first in Seville, which became the most populous city in the Spanish Empire, and two centuries later in Cádiz until its disappearance in that same century. After the arrival of Christopher Columbus in America, Andalusia played a fundamental role in his discovery and colonization. However, there was no real economic development in Andalusia due to the numerous companies of the Crown in Europe. The social and economic wear and tear became widespread in the XVII century and culminated in the conspiracy of the Andalusian nobility against the government of the count- Duke of Olivares in 1641.

In the middle of the XVI century some inhabitants of Andalusia and Extremadura emigrated to New Spain, influenced by Carlos I and, later, by his son Felipe II, settling in the current states of Veracruz, Hidalgo and the State of Mexico, and in the sociocultural region of El Bajío, thus contributing to the nascent Spanish culture in Mexico.

The Bourbon reforms of the 18th century did not remedy the fact that Spain in general and Andalusia in particular were losing political and economic weight in the European and global context. Likewise, the loss of the Spanish overseas colonies will gradually remove Andalusia from the mercantilist economic circuits.

This situation improved during the following century as the Andalusian industry played an important role in the Spanish economy during the XIX century. In 1856, Andalusia was the second Spanish region in terms of degree of industrialization. A century later it was already practically at the bottom, with an industrialization index of less than 50 percent of the average Spanish level. While between 1856 and 1900 Andalusia had an industrialization index higher than the national average in the food, metallurgy, chemical and ceramic branches, from 1915 this supremacy was reduced to the food and chemical branches.

After that expansive century, through much of the 20th century and early XXI, Andalusia, and despite the fact that it was established as an autonomous community in 1981, it cannot match its development rates to the rest of Spain, being the region with the highest unemployment of the entire EU and the lowest per capita income in the country.

Government and politics

Andalusia acceded to autonomy through the so-called aggravated route or procedure, included in article 151 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978. The process required that the initiative be approved by an absolute majority of the voters in the proposed community and in each province and not by a majority of votes cast. Although the initiative obtained majority support throughout Andalusia, the required majority was lacking in the province of Almería (see Referendum on the initiative of the autonomous process of Andalusia), where although a majority of the votes was reached, the abstention did not allow a majority to be reached of voters. The situation presented a problem because the same article 151 mandates a waiting period of 5 years in case of failure, which was not finally considered and the real majority obtained was taken into account. Following this procedure, the Autonomous Community of Andalusia was constituted on February 28, 1980 after holding a referendum, declaring in the first article of its Statute of autonomy (1981) that such autonomy is justified by "historical identity, in the self-government that the Constitution allows to all nationalities, in full equality to the rest of the nationalities and regions that make up Spain, and with a power that emanates from the Constitution and the Andalusian people, reflected in its Statute of Autonomy".

In October 2006, the Constitutional Commission of the Cortes Generales approved, with the favorable votes of PSOE, IU and PP, a new Statute of autonomy, whose preamble mentions, first, that in the Andalusian Manifesto of 1919 Andalusia was described as a national reality, to continue exposing, its current status as a nationality within the indissoluble unity of the Spanish Nation. Later in its articles it defines itself, more specifically, as a historical nationality, unlike the previous statute (of 1981) where it was defined, simply, as a nationality.

On November 2, 2006, the Congress of Deputies ratified the text of the Constitutional Commission with 306 votes in favor, none against, and two abstentions, marking the first time that an Organic Law of an Autonomy Statute was approved without any votes against. It was approved by the Senate, in a plenary session held on December 20, 2006, and ratified in a referendum by the Andalusian People on February 18, 2007.

The Statute of Andalusia regulates the different institutions in charge of government and administration within the Community. The Junta de Andalucía is the main institution in which the government is organized. On the other hand, there are other self-government institutions: the Andalusian Ombudsman, the Advisory Council, the Chamber of Accounts, the Audiovisual Council of Andalusia and the Economic and Social Council.

Andalusian Government

The Junta de Andalucía is the institution that organizes the self-government of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia. It is made up of: the president of the Junta de Andalucía, who is the supreme representative of the autonomous community, and the ordinary representative of the State in it. His election takes place by the favorable vote of the absolute majority of the Plenary of the Parliament of Andalusia and his appointment corresponds to the king.The president of the Board is Juan Manuel Moreno Bonilla.

The Governing Council, which is the highest political and administrative body of the Community, to which corresponds the exercise of regulatory power and the performance of the executive function. It is made up of the president of the Junta de Andalucía, who he presides, and by the councilors appointed by him to take charge of the various Departments (Councils). This structure is established by Decree of the President 6/2019, of February 11, which modifies Decree of the President 2/2019, of January 21, of the Vice-Presidency and on the restructuring of Ministries. During the XI legislature (started in 2019) the Government of Andalusia was a sum of the coalition of the Popular Party and Ciudadanos with the external support of Vox, with a total of 11 Ministries, 6 belonging to the Popular Party and 5 to Ciudadanos.

In the XII Legislature that began in July 2022 after the absolute majority of the Popular Party, the Andalusian Government will be composed as follows:

- President: Juan Manuel Moreno Bonilla.

- Presidential, Interior, Social Dialogue and Administrative Simplification: Antonio Sanz

- Council of Social Inclusion, Youth, Families and Equality: Loles López Gabarro

- Department of Development, Land Articulation and Housing: Marifrán Carazo

- Consejería de Desarrollo Educativo y Formación Profesional: Patricia del Pozo Fernández

- Consejería de Economía, Hacienda y Fondos Europeas: Carolina España Reina

- Consejería de Susstenibilidad, Medio Ambiente y Economía Azul: Ramón Fernández-Pacheco

- Consejería de Agricultura, Pesca, Agua y Desarrollo Rural: Carmen Crespo

- Department of Justice, Local Administration and Public Service: José Antonio Nieto

- Employment, Business and Self-employed Counseling: White Rocío Eguren

- Policy advice for Industry and Energy: Jorge Paradela Gutiérrez

- Consejería de Turismo, Cultura y Deporte: Arturo Bernal Bergua

- Consejería de Salud y Consumo: Catalina García Carrasco

- Universidad, Investigación e Innovación: José Carlos Gómez Villamandos

The Parliament of Andalusia is the autonomous legislative assembly, which is responsible for the preparation and approval of Laws and the election and dismissal of the president of the Junta de Andalucía.

The elections to the Parliament of Andalusia are the democratic formula by which the citizens of Andalusia elect their 109 political representatives in the autonomous chamber. After the approval of the Andalusian Statute of Autonomy through Organic Law 6/1981 of December 30, 1981, the first elections to its autonomous Parliament were called for May 23, 1982. Subsequently, elections have been held in 1986, 1990, 1994, 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012, 2015, 2018 and 2022.

| PSOE | P | IU | PA | UCD | We can. | Citizens | Go ahead. | Vox | Total Scalls | List more voted | Gobernó | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Votes | Scalls | Var | Votes | Scalls | Var | Votes | Scalls | Var | Votes | Scalls | Var | Votes | Scalls | Var | Votes | Scalls | Var | Votes | Scalls | Var | Votes | Scalls | Var | Votes | Scalls | Var | |||||

| I | 1982 | 52.56% | 66 | 20.48% | 17 | 8.53% | 8 | 5.38% | 3 | 13.05% | 15 | 109 | PSOE | PSOE | |||||||||||||||||

| II | 1986 | 47.22% | 60 | -6 | 22.26% | 28 | +11 | 17.8% | 19 | +11 | 5.88% | 2 | -1 | 109 | PSOE | PSOE | |||||||||||||||

| III | 1990 | 50.12% | 62 | +2 | 22.40% | 26 | -2 | 12.80% | 11 | -8 | 10.86% | 10 | +8 | 109 | PSOE | PSOE | |||||||||||||||

| IV | 1994 | 38.71% | 45 | - 17 | 34.36% | 41 | +15 | 19.14% | 20 | +9 | 5.79% | 3 | -7 | 109 | PSOE | PSOE | |||||||||||||||

| V | 1996 | 44.05% | 52 | +7 | 33.96% | 40 | -1 | 13.97 per cent | 13 | -7 | 6.66% | 4 | +1 | 109 | PSOE | PSOE + PA | |||||||||||||||

| VI | 2000 | 44.32% | 52 | = | 38.02% | 46 | +6 | 8.11% | 6 | -7 | 7.43 per cent | 5 | +1 | 109 | PSOE | PSOE + PA | |||||||||||||||

| VII | 2004 | 50.36% | 61 | +9 | 31.78% | 37 | -9 | 7.51% | 6 | = | 6.16% | 5 | = | 109 | PSOE | PSOE | |||||||||||||||

| VIII | 2008 | 42.41% | 56 | -5 | 38.45% | 47 | +10 | 7.06% | 6 | = | -5 | 109 | PSOE | PSOE | |||||||||||||||||

| IX | 2012 | 39.56% | 47 | -9 | 40.67% | 50 | +3 | 11.35% | 12 | +6 | 109 | P | PSOE + IU | ||||||||||||||||||

| X | 2015 | 35.43% | 47 | = | 26.76% | 33 | - 17 | 6.89% | 5 | -7 | 14.84 per cent | 15 | +15 | 9.28% | 9 | +9 | 109 | PSOE | PSOE | ||||||||||||

| XI | 2018 | 27.95% | 33 | -14 | 20.75% | 26 | -7 | 18.27% | 21 | +12 | 16.18% | 17 | -3 | 10.97% | 12 | +12 | 109 | PSOE | PP + Citizens | ||||||||||||

| XII | 2022 | 24.09% | 30 | -3 | 43.13% | 58 | +32 | 3.29% | 0 | -21 | 13.46% | 14 | +2 | 109 | P | P | |||||||||||||||

Judicial branch

The highest jurisdictional body of the autonomous community is the Superior Court of Justice of Andalusia, based in Granada, before which the successive procedural instances are exhausted without prejudice to the jurisdiction that corresponds to the Supreme Court. However, the Superior Court of Justice of Andalusia is not a body of the autonomous community but is part of the Judicial Power, which is unique throughout the Kingdom and cannot be transferred to the autonomous communities. The Andalusian territory is divided into 88 judicial districts.

Territorial organization

- Provinces

Andalusia is divided into eight provinces, created by Javier de Burgos by Royal Decree of November 30, 1833, which are the following:

- Municipalities

In Andalusia there are 785 municipalities divided among the eight provinces. The municipal entities in Andalusia are regulated by the Andalusian Statute of Autonomy in its Title III, in articles ranging from 91 to 95, where it is established that the municipality It is the basic territorial entity of Andalusia, within which it enjoys its own legal personality and full autonomy in the field of its interests. Its representation, government and administration correspond to the respective Town Halls, which have their own powers on matters such as urban planning, community social services, water supply and treatment, waste collection and treatment and the promotion of tourism, culture and sports among others. subjects established by law.

- Local entities

The separate population centers within a municipal area agree to the administration of their own interests, constituting autonomous local entities under the name of pedanías, villas, villages, or any other recognized establishment in the place, in accordance with the principle of maximum proximity of administrative management to citizens.

- Regions

The Andalusian regions have never been officially regulated as in other autonomous communities, but they are recognized for geographical, cultural, historical or administrative reasons. This has been echoed in the new Statute of Autonomy in which the regions are mentioned in article 97 of Title III, where the meaning of region is defined and the bases are laid for future legislation on these.

The current figure that comes closest to the definition of region given by the statute is that of commonwealth, so these could possibly become the germ of future Andalusian regions. On the other hand, the development of the LEADER and PRODER groups, created with the purpose of requesting European aid for rural development, is also gaining a certain dimension. At present, practically all of the Andalusian municipalities are part of one of these groups, except for the provincial capitals and their metropolitan areas. These groups are made up of municipalities freely united by their economic interests and are endowed with funds in many cases used for the external dissemination of their identity.

- Community

The Andalusian associations are an instrument for the socioeconomic development of the region or regions on which they act in coordination with the town halls of the municipalities that comprise it, the Junta de Andalucía, the General Administration of Spain and the European Union.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, Andalusia has traditionally been divided into two large subregions: Upper or Eastern Andalusia (provinces of Almería, Granada, Jaén and Málaga) and Lower or Western Andalusia (provinces of Huelva, Seville, Cádiz and Córdoba).

Population

Andalusia is the leading Spanish autonomous community in terms of its population, which as of January 1, 2018 stands at 8,384,408 inhabitants with 82 municipalities with more than 20,000 inhabitants. This population is concentrated, above all, in the provincial capitals and in the coastal areas, so the level of urbanization in Andalusia is quite high; Half of the Andalusian population is concentrated in the twenty-nine cities with more than fifty thousand inhabitants. The population is aging, although the immigration process is favorably altering the inversion of the population pyramid.

| Graphic of demographic evolution of Andalusia between 1787 and 2021 |

|

Source: Spanish National Statistical Institute - Graphical development by Wikipedia. |

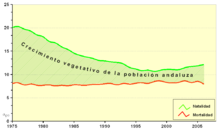

On the threshold of the XX century, Andalusia was immersed in the last phase of the demographic transition. Mortality stagnated at around 8-9 ‰, so the birth rate and migratory movements marked the evolution of the population.

In 1950 the weight of the Andalusian population with respect to the national population was 20.04%, while in 1981 it would drop to 17.09%. In these decades the slow decline in population, caused by emigration, could not be offset by the higher birth rate compared to other regions of Spain. Average year-on-year growth was much more moderate than on previous dates.

Since the 1980s, the opposite process occurred. The birth rate suffered a sharp drop, as in the rest of Spain and in developed countries. Although, in the Andalusian community the decline was slower and this transition was prolonged. Therefore, the basis of its relative demographic recovery with respect to Spain is the return of immigrants to Andalusia. During the 1990s a new immigration phenomenon that will affect both Andalusia and the rest of Spain.

At the beginning of the XXI century, there was a slight upturn in the birth rate, largely conditioned by the increase in births of children of immigrants, which together with the traditional vitality of the Andalusian population, leaves a panorama more favorable to the rejuvenation of the population than in other communities in Spain and European countries. In 2018, the weight of the Andalusian population with respect to the total of Spain is 17.98%.

Distribution

The distribution of the population is a factor of imbalance and contrast between the different areas of Andalusia. In 2018, the Andalusian population density was 96.08 inhab./km², practically 4.2% above the national figure, which is 92.21 inhab./km².

In an analysis of the provincial distribution in 2008, the concentration of large cities around the Guadalquivir-Genil axis and the Mediterranean coast is clear. The provinces of Seville, Málaga and Cádiz stand out in this imbalance compared to the rest of Andalusia. Between these three provinces they account for 57% of the total population. Regarding the percentage of population in the capitals, in 1991 it was 34.68% of the total; in 2007 the figure has fallen to 29.75% due to the increase in population in urban agglomerations and in the coastal zone. Among the six most populous cities in Spain, two of them are Andalusian, Seville with 700,000 inhabitants and Malaga with 568,000 inhabitants, in addition Córdoba exceeds 300,000 inhabitants and two other municipalities exceed 200,000 inhabitants (Granada and Jerez).

Continuing the analysis in 2018, we see how population growth stagnates, continuing the significant loss of population in the areas of the mountains (Sierra Morena and Cordilleras Béticas) while it continues to increase on the coast and the metropolitan areas, mainly in the Seville metropolitan area and the Malaga metropolitan area.

Structure

At the beginning of the XXI century, the population structure of Andalusia shows a clear demographic maturity, the result of the long process of demographic transition that lasted in Andalusia until well into the XX century.

Observing the comparison between the years 1986 and 2008, the changes in the structure of the population can be explained:

- A clear decline in the young population, due to the significant decline in birth.

- Increasing adult population, due to the entry into adult phase of the large number of population born after the economic boom of the 1960s —Baby boom- To this fact, the large contribution of immigrant population, usually in adulthood, must be joined.

- Increased adult population, due to increased life expectancy.

Regarding the structure by sex, there are two aspects to highlight: the highest proportion of the elderly female population —due to the greater life expectancy of women— and on the other hand, the highest percentage of the adult male population, largely partly due to the contribution of the immigrant population that is mostly male.

Immigration

5.35% of the Andalusian population is of foreign nationality, a percentage three points lower than the national average. However, immigrants are distributed very unevenly throughout the autonomous community: the province of Almería is the third in Spain with the highest percentage of foreign population (with 15.20%), while Jaén (with 2.07 %) and Córdoba (with 1.77%) are the two Andalusian provinces with the lowest percentage of foreigners. The predominant nationalities are Moroccan (17.79% of all foreigners) and British (15.25% and the majority in Malaga), although by geographical area of origin, Latin Americans are the most numerous. The number of Moroccans is close to 100,000.

Demographically, this group has contributed a significant number of active population to the Andalusian job market, and a rejuvenation of the population is beginning to take place, which is appreciable in the slight increase in the birth rate, the majority of which is the result of the birth of immigrants.

Main Cities

Infrastructures and services

Transportation

Transportation systems are an essential element of the structuring and functioning of the territory. The infrastructure networks are the support of the different flows that facilitate the territorial articulation, the development and distribution of economic activities, interurban displacements, among other aspects.

In urban transport, pedestrian and non-motorized transport coexist at a disadvantage with the use of private vehicles and with an insufficiently developed public transport system. This means that some of the Andalusian capitals are reinforcing their public transport systems and implementing greater advantages for the use of bicycles, in which Córdoba, Granada, Málaga and Seville stand out in recent years, in the case of Seville it has gone introducing the Metro (subway) service in its metropolitan area—2009-present project—

The conventional rail network remains similar to that of 100 years ago, with a centralized structure towards Seville and Madrid, lacking direct connections between many of the provincial capitals. Two main routes are the one that connects Algeciras with Seville and the one that unites Almería and Granada with Madrid, which connects Andalusia with the capital of the State. Through Córdoba it is done by High Speed and by Jaén by conventional way. The Andalusian High Speed was a pioneer in Spain since the first route was from Seville to Madrid in 1992. In 2008 the AVE line between Malaga and Madrid, via Córdoba, came into operation.

The main axes of the road network have been converted into highways to a large extent, forming an extensive network. The E-05 (A-4) that goes from Madrid to Seville and continues to Cádiz, enters through Despeñaperros and passes through Bailén and Córdoba. From Bailén starts the A-44 (E-902) which has a branch to Granada and Motril. The autonomous community is crossed from east to west by the A-92 motorway that connects Seville, Málaga, Granada and Almería with the A-49 Seville-Huelva motorway and which continues west to Portugal. There is also a transversal North-South axis that connects Córdoba with Málaga A-45. All in all, accessibility needs have not yet been fully resolved, congesting many sections of the road network during holiday seasons and supporting a lot of heavy traffic from the agricultural areas of the coast. Specifically, the passage of North Africans working in Europe increases the use of connections to Tarifa and Algeciras.

Among the ports of general interest in Andalusia, the Bahía de Algeciras port stands out, both for passenger and freight transport, being the port with the highest traffic in Spain with almost 70 million tons in 2009. Also with a certain Functional specialization completes the commercial port panorama: the port of Malaga with 5.3 million tons of merchandise, being the second peninsular cruise port, the port of the Bay of Cádiz with four million tons, the port of Huelva with 17.6 million tons and the port of Seville with 4.5 million tons, the only commercial river port in Spain.

Andalusia had six public airports in 2008, all classified as being of general interest and therefore international. Passenger traffic is highly concentrated, with the Málaga-Costa del Sol airport accounting for 60.67% of the total passengers in the community. The two airports with the most traffic (Málaga and Seville airport) account for 80.79% of the total and if Jerez airport is added to these, 87.96%.

The Governing Council has approved the Infrastructure Plan for Transport Sustainability in Andalusia (PISTA) 2007-2013, which will involve an investment of 30,000 million euros in transport infrastructure and services.

Energy

The scarcity of fossil fuel resources, or their low calorific value, causes a strong dependence on imported oil, in the Andalusian energy sector, although Andalusia has great potential for the development of renewable energies, especially of solar and wind energy. The Andalusian Energy Agency, created in 2005, is the government body in charge of developing regional policy in relation to the community's energy supply.

The infrastructure for the production of electricity is made up of eight large thermal power plants; more than sixty small hydraulic power stations; two wind farms; and fourteen thermal cogeneration plants. The largest company in this sector was the Compañía Sevillana de Electricidad, founded in 1894, today absorbed by Endesa.

Since March 2007, Andalusia has housed the first concentrated solar power plant in Europe: the PS10 solar plant, located in Sanlúcar la Mayor and carried out by an Andalusian company, Abengoa. There are also other smaller plants, such as those of Cúllar and Galera (Granada), recently inaugurated by Geosol and Caja Granada. Also in the province of Granada, specifically in Hoya de Guadix, two large solar thermal power plants are planned (Andasol I and II) that will supply electricity to nearly half a million homes. Apart from solar thermal, solar energy has also been developed photovoltaic, highlighting the plant installed in El Coronil that produces more than 20 MW in part with single-pole double-axis trackers. In the field of research and development of solar energy, an important center is the Plataforma Solar de Almería, one of the most important in Europe.

The largest company in the wind power sector is Sociedad Eólica de Andalucía, which emerged from the merger of the companies Planta Eólica del Sur S.A. and Energía Eólica del Estrecho S.A.

Education

As in the rest of the State, basic education is compulsory and free for everyone. Basic education comprises ten years of schooling and takes place between the ages of six and sixteen, after which the student can access the baccalaureate, intermediate vocational training, intermediate visual arts cycles and design, middle school sports education or the world of work. In addition, there are other adult training centers, as well as additional resources (it is the Spanish autonomous community with the most public libraries).

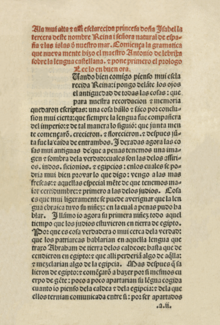

The first universities in Andalusia were created at the end of the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance. The oldest was the Granada Madraza, founded in 1349 by the Nasrid king Yusuf I and destroyed in 1499 by Cardinal Cisneros. In 1531, at the initiative of Carlos I, the University of Granada was created. The other historical universities in Andalusia are the University of Seville, dating from the early XVI century, and the now-defunct universities of Baeza, founded in 1538 and suppressed in 1824, and that of Osuna, with the same dates of creation and suppression.

University studies are structured in cycles and take credit as a measure of the study load, as established in the Declaration of Bologna, to which the Andalusian universities are adapting together with the other universities of the European Higher Education Area. In the 2008-2009 academic year, Andalusia had ten public universities and one private one.

Health

Health care is universal and free, comparable to the health average in Spain. Andalusia achieved ownership of the health powers with the promulgation of its Statute of Autonomy, which was developed through a process of transfers of health powers from the State to the autonomous community. In this way, the Andalusian Health Service currently manages practically all of the public health resources of the Community, with exceptions such as those of the health resources dependent on the Ministry of Justice (Penitentiary Institutions) and the Ministry of Defense (military hospitals)., among other.

Science and technology

Andalusia contributes 14% of Spanish scientific production, preceded only by Madrid and Catalonia, although internal investment in R+D+i, as a proportion of the Gross Domestic Product, is lower than the Spanish average. The limited capacity for research and innovation in the company and the low participation of the private sector in research spending results in an ostensible concentration of research in the public sector.

The Ministry of Innovation, Science and Business is the regional body that covers the competences of the university, research, technological development, industry and energy. This Ministry coordinates and promotes scientific and technical research through specialized centers and initiatives such as the Andalusian Center for Marine Science and Technology or the Andalusian Technology Corporation, among others.

In the field of private companies, although they have also been promoted by the public administration, the technological spaces distributed throughout the community have been of fundamental importance, among which the Technological Park of Andalusia and Cartuja 93 stand out. Some of these parks They specialize in a specific sector such as Aerópolis in the aerospace sector or Geolit in the agri-food sector.

Economy

The economic capital of Andalusia is Seville, as it has a higher GDP, brings together more companies and has a more diversified, seasonally adjusted and stable economy.

General features

The main features of the Andalusian economy are:

- According to Eurostat, with data from 2012, Andalusia has the highest unemployment rate in the entire EU. In 2013, this negative data continued to increase to 36,87 % in the first quarter (the average of Spain is 25.02 %).

- In 2013, Andalusia stood as the autonomous community with the poorest of Spain, one in four poor Spanish is Andalusian and one in three Andalusians is poor. About 3.5 million Andalusians live on the threshold of misery, which accounts for more than 40% of the population according to the Arope rate. According to the National Statistical Institute (INE) Living Conditions Survey (ECV), 31 per cent of Andalusians living below the poverty line and placing 55 per cent of households at serious risk.

- According to the Regional Accounting developed by the National Statistical Institute, the per capita income of the community was located in 2008 at 18 155 €, which is the second lowest in Spain.

- Andalusia is the autonomous community with the highest number of officials, with 499 974 people (2010). However, it is around the national average of staff for every 1000 inhabitants (60.93 per thousand in Andalusia and 58.78 per national average) and below autonomous communities such as the Canary Islands, Madrid, Castilla-La Mancha, Aragon, Castilla y León and Extremadura. For provinces, Seville, is the largest number with 120 806. The province of Seville accumulates more staff than 9 CC. AA. and 47 Spanish provinces, and concentrates 24.16 % of officials in the region. The rest of the officials of the region would be distributed in Cadiz with 80 502; Malaga, with 76 127; Granada, with 61 450; Cordoba, with 48 550; Jaén, with 41 102; Almeria, with 37 806; and Huelva, with 33 631.

- Negative trade balance, worsening in recent years due to the weight of oil imports and consumer goods (imports 14 261 million euros, exports 17 535 million euros).

- The stagnation of the industry (12 % of the VAB), within which the agro-food industry remains of great importance.

- Excessive construction weight, principal responsible for the growth of the Andalusian VAB in the first decade of 2000, with a contribution of 13 % to the VAB in 2005.

- The services sector is approximately 62 % of the VAB. With a special relevance of the tourist sector, with more than 21.8 million tourists received in the autonomous community in 2011.

Tertiary sector

The tertiary or service sector, both in terms of production and employment, has experienced very significant growth in its share of the economy in recent decades. From being a minority sector, it has become a vast majority as in most Western economies.

This process, which has been called tertiarization of the economy, has manifested itself in Andalusia in a peculiar way. In this way, in 1975 the services sector produced 51.1% of the Andalusian Gross Value Added (VAB) and gave employment to 40.8%, while in 2007, it produced 67.9% of the GVA and the 66.42% of jobs. However, this growth in the tertiary sector occurred earlier than in other developed economies and was independent of the industrial sector.

In Andalusia the anachronistic development of the tertiary is due to two main reasons:

- The Andalusian capital in the face of the impossibility of competing with the industry in the developed regions is forced to undertake activities of easier access.

- The absence of a strong industrial sector that can absorb the surplus of labour from agriculture and the one created by the disappearance of the craft leads to the proliferation of certain types of services with low productivity. It is therefore the role that the Andalusian economy plays, within the process of uneven development, which results in a hypertrophied and unproductive tertiary, which contributes to the reproduction of the conditions of little dynamism, hindering the accumulation of capital.

Tourism sector

In 2011, with 7,218,291 foreign visitors, it was established as the fourth Spanish community in terms of international tourism, (not counting national tourists, with whom it ranks first) whose main destinations within the region They are: Seville, the Costa del Sol and Sierra Nevada. The situation of Andalusia, in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, makes it one of the warmest places in Europe. The Mediterranean climate predominates throughout the territory, which provides a large number of hours of sunshine, which, together with its beaches, sets the conditions for the development of "sun and beach" tourism.

The coast is presented as the most important asset from the tourist point of view, although it is also true that it is where its intensive nature causes a greater environmental impact, since it is also where most visitors are concentrated.

Its coast is bathed by the Atlantic Ocean, to the west, where the Costa de la Luz is located, and by the Mediterranean Sea, where the eastern coast is divided into the Costa del Sol, Costa Tropical and Costa de Almería. Although the granting of private awards such as the 84 blue flags awarded in 2004 (66 beaches, 18 marinas) may indicate a good state of conservation, in terms of sustainability, accessibility and quality, other organizations such as Ecologistas en Acción or Greenpeace, however, they manifest themselves in the opposite direction.

Regarding cultural tourism, the community has a great patrimonial and historical wealth. Andalusia has monuments such as the Mosque of Córdoba, the Alhambra in Granada and the Giralda in Seville. Also notable are the cathedrals, castles or fortresses, monasteries and historic quarters of monumental cities, such as the declared World Heritage sites of Úbeda and Baeza (Jaén).

Each of the provinces displays a wide variety of architectural styles (from Islamic to Renaissance to Baroque architecture). Another of the cultural attractions is the Columbian Places (Palos de la Frontera, La Rábida and Moguer) in Huelva, places especially linked to Columbus's first voyage that resulted in the discovery of America. Regarding archaeological tourism, Andalusia has archaeological sites of great interest, such as Itálica, the Roman city where the emperors Trajan and Adriano originated, Baelo Claudia or Medina Azahara, a city-palace ordered to be built by the Cordovan caliph Abderramán III, in which, even though there is a lot that can be visited, the proportion of what has already been excavated with respect to the total number of sites is minimal.

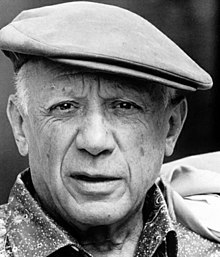

On the other hand, Andalusia saw the birth of great painters, such as Picasso (Málaga), or Murillo and Velázquez (Seville), an important circumstance also from the tourist point of view, since as a result of it institutions such as the Fundación Picasso Museo Casa Natal or the Museo Picasso Málaga itself, as well as the Museo Casa de Murillo in Seville, designed to make these artists known. It also has a range of museums spread throughout its geography, which show not only paintings, but also archaeological remains and pieces of goldsmithing, ceramics, pottery, artistic works that try to show the traditions and typical crafts of the region.

The Governing Council declared Tourist Municipalities in Almería: Roquetas de Mar; in Cádiz: Chiclana de la Frontera, Chipiona, Conil de la Frontera, Grazalema, Rota and Tarifa; in Granada: Almunecar; in Huelva: Aracena; in Jaén: Cazorla; in Malaga: Benalmádena, Fuengirola, Nerja, Rincón de la Victoria, Ronda and Torremolinos; in Seville: Santiponce.

Secondary sector

The Andalusian industrial sector has traditionally had little weight in the economy and has been characterized by its weakness. However, in absolute values the industry contributed 11,979 million euros in 2007 and paid more than 290,000 workers. The contribution of production represents 9.15%, below the 15.08% of the Spanish economy, a situation increased with the decrease in the weight of the industrial sector with respect to the Andalusian economy, despite the slight increase in the weight of the community in the last five years.

When analyzing the different subsectors of the Andalusian industry, the agri-food sector accounts for more than 16% of total production. In a comparison with the Spanish economy, this agri-food subsector is practically the only one that has a certain weight in the national economy with 16.16%. Far behind is the transport materials manufacturing sector, which accounts for just over 10% of the Spanish economy. Companies such as Cruzcampo (Heineken Group), Puleva, Domecq, Renault Andalucía, Santana Motor or Valeo are exponents of these two subsectors. It is worth noting the Andalusian aeronautical sector, which is the second nationally only behind Madrid and represents approximately 21% of the total in terms of turnover and employment, highlighting companies such as Airbus, Airbus Military, or the recently created Alestis Aerospace. In the opposite direction, the low weight of the Andalusian economy in sectors as important as textiles or electronics at the national level is very symptomatic.

Another characteristic of Andalusian industry is its majority specialization in industrial activities involving the transformation of agricultural raw materials and minerals. The vast majority of companies are very small and only companies with public participation or external capital are capable of developing large business structures.

Exports of high and medium technology products from Andalusia reached 7,628 million euros between January and October 2022, which represents its historical record for this period since comparable records exist (1995), thanks to growth in the 21.6% year-on-year. An increase higher than the average for Spain (+20.9% to 138,644 million). Seville is the main technological hub of Andalusia, exporting 33% of all high and medium technology products.

Primary sector

The primary sector, despite being the one that contributes the least GVA to the economy, still represents a certain relative importance with respect to the rest of the productive sectors. This importance becomes greater if we compare it with the primary sector of other Western economies, where it has been reduced to a minimum. The primary sector, with a long Andalusian tradition, produces 8.26% of the total and employs 8.19% of the active population. In monetary terms, it can be considered a sector of growing competitiveness in recent years.

The primary sector can be divided into a number of subsectors: agriculture, fishing, livestock, hunting, forestry, and mining.

Agriculture, livestock, hunting and forestry

Until a few decades ago, Andalusian society was mostly agrarian, which explains why 45.74% of the Andalusian territory is cultivated land. Dry-land herbaceous crops -cereals and sunflower-, spread over a large part of the territory, stand out above all in the large countryside of the Guadalquivir valley and the highlands of Granada and Almería -with a significantly lower yield and focused on barley and oats-. Among the irrigated herbaceous crops, corn, cotton and rice stand out, preferably located in the valley of the Guadalquivir and Genil.

The woody crops are led by the olive tree, preferably located in the subbético of Cordoba and Jaen, where the irrigated olive grove reaches a high yield providing a significant percentage to the final agricultural production. The vine is widely cultivated in various areas such as the Marco de Jerez, the Condado de Huelva, Montilla-Moriles and in Malaga. On the other hand, the fruit trees, mainly citrus, are located in the plain of the Guadalquivir due to its water requirements; while the almond tree, a rainfed crop, extends across the highlands of Granada and Almería.

In monetary terms, the most productive and competitive agriculture in Andalusia is intensive, linked to coastal fertile plains or sandy areas -forced cultivation in Almería and Huelva-. This agriculture contributes the largest proportion to the final Andalusian agricultural product with products such as vegetables, flowers or strawberries.

Andalusian organic farming is also undergoing extensive development, mainly oriented towards exports to European markets, with an incipient development of internal demand.

Livestock farming is an activity with a long tradition, although it is currently mostly restricted to pastures in montane areas, with less pressure from different land uses. Thus, the livestock sector occupies a semi-marginal place in the Andalusian economy, contributing only 15% to final agricultural production, compared to 30% in Spain, while the agricultural sector contributes 30%.

The extensive cattle ranching is based on the use of natural or cultivated mountain pastures for grazing cattle herds. This livestock subsector includes a large part of beef cattle, all sheep and goats, as well as free-range pigs - products derived from Iberian pigs stand out. The autochthonous sheep and goat herds present great potential in a Europe with a surplus of many livestock products, but a deficit in sheep and goat derivatives: meat, milk, leather, among others.

The intensive livestock farming is located mainly in the countryside and is based on the cultivation of fodder species to feed livestock. Although their productivity is much higher than that of extensive livestock, compared to other Spanish and European regions, they have not managed to match their productions and consolidate themselves in the market.

Modern intensive industrial livestock farming is adapted to today's economy. Its facilities have been located in the immediate vicinity of the points of demand. It is based on the use of industrial feed.

The hunting activity maintains a relative importance. At present, it has lost its character of activity for obtaining food. And it has become a leisure activity linked to mountainous spaces, where it is a complementary activity, not insignificant, to forestry and livestock. The community has 270,000 federated hunters and more than 25,000 hunting grounds.

Forest areas in Andalusia are of great importance due to their extension (50% of the Andalusian territory) and due to other aspects that are difficult to quantify economically such as soil fixation, water regulation, maintenance of flora and fauna, which are of great interest environment, which must be strengthened and regulated to safeguard these spaces of great environmental importance.

The production value of forest spaces barely accounts for 2% of agricultural production. Logging, mainly cultivated species -eucalyptus in Huelva and poplar in Granada- and cork in Sierra Morena and Los Alcornocales are the main productive activities.

Fishing