Amadeo I of Spain

Amadeo I of Spain, called “the Knight King” or “the Elect” (Turin, May 30, 1845-Turin, January 18, 1890), was King of Spain from January 2, 1871 to February 11, 1873. He was also the first Duke of Aosta and head of the Savoy-Aosta branch.

He was elected King of Spain by the Cortes Generales in 1870 after the dethronement of Elizabeth II in 1868. His reign in Spain, which lasted just over two years, was marked by political instability. The six cabinets that followed one another during this period were unable to solve the crisis, aggravated by the independence conflict in Cuba, which had begun in 1868, and a new Carlist war, which began in 1872. His abdication and his return to Italy in 1873 led to the declaration of the First Spanish Republic.

Biography

Youth

Amadeo was the third son of Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy, last King of Sardinia (1849-1861) and first King of Italy (1861-1878), and Archduchess Maria Adelaide of Habsburg-Lorraine (great-granddaughter of Charles III of Spain, therefore Amadeo's great-great-grandfather). His brother Umberto his would become King Umberto I of Italy. At his birth he obtained the title of Duke of Aosta with which he inaugurated a dynasty that continues to this day.

He entered the army with the rank of captain in 1859 and participated in the Third Italian War of Independence (1866) as a major general, leading a brigade to Monte Croce in the battle of Custoza, where he was wounded and by the who obtained the gold medal for military valor.

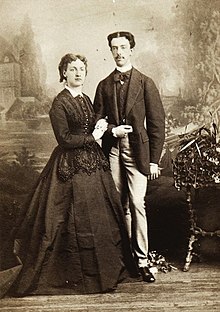

First marriage

In 1867 Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy yielded to the pleas of the deputy Francesco Cassins and, on May 30 of the same year, Amadeo married the Piedmontese noblewoman Maria Victoria dal Pozzo della Cisterna, VI Princess of La Cisterna and of Belriguardo. The king had initially been against this union, since, despite being of princely rank, the family was still too low to aspire to be related to the Savoys. In addition, for his third son Víctor Manuel II had planned a marriage with a foreign princess, perhaps German, in order to strengthen political and diplomatic ties with other states, but in the end he decided to comply with Amadeo's wish to marry with the woman he loved. The wedding day of Prince Amadeo and Doña María Victoria was marred by the death of a stationmaster who was crushed under the wheels of the honeymoon train.

In addition to the emotional value, what finally convinced Victor Emmanuel II was the rich heritage that the young princess brought as a dowry and some of her family ties that, to a small extent, could benefit the newly united Italy: the mother of Maria Victoria, Luisa de Mérode-Westerloo, was the younger sister of Antoinette de Mérode-Westerloo, wife of Prince Charles III of Monaco.

What Victor Emmanuel II could not foresee, or perhaps tried to hide, was however that his son Amadeo was an incurable lover, to the point that in March 1870 the Duchess of Aosta appealed in writing to the King to expose her complaints about her husband's marital infidelities, which caused her pain and shame in society circles. The king, in response, wrote to her that, although she understood her feelings, she was not in a position to judge her husband's behavior and that her jealousy was unworthy of a duchess of the House of Savoy.

Candidate for the throne of Spain

In 1868 Victor Emmanuel II became actively concerned with securing the vacant throne in the Spanish succession, which ended in 1870 for a member of the House of Savoy.

Ferdinand VII of Bourbon had died in 1833 without male heirs and, in anticipation of this, had abolished the Salic Law in 1830 in favor of his newborn daughter Isabel II. The succession was contested by Carlos de Borbón, brother of the deceased monarch, and by the conservative Carlists, supporters of the succession according to the traditional Salic law.

The Revolution of 1868 deposed Isabel and gave rise to a provisional government headed by Francisco Serrano, and of which the other rebel generals were also a part. The new government convened the Constituent Cortes, which with a large monarchical majority, proclaimed the Constitution of 1869, which established a constitutional monarchy as a form of government. An inherent difficulty of the regime change was finding a king who would accept the position, since Spain at that time was a country that had been led to impoverishment and a convulsed state, and a candidate was sought that would fit the constitutional form of monarchy.

Finally they found their monarch in the person of the Duke of Aosta, Amadeo of Savoy, son of the King of Italy, who brought everything together for the position: coming from an old dynasty (linked to the Spanish), progressive and baptized Catholic although, according to some sources, a Freemason, reaching the 33rd degree of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite. Regarding this, the republican writer Miguel Morayta y Sagrario (1834-1917) warned of the falsehood of the document received on behalf of Italian Freemasonry, by the lodges of Madrid, in which the status of Amadeo de Saboya as a Freemason was indicated. Morayta claimed that it was a forgery made in Madrid itself by a member of the Grand Orient of Spain, coinciding with the Amadeí campaign. On the other hand, the latest investigations carried out by Alvarado Planas and gathered in his publication Masones en la nobility de España (2016) point out that, despite what has been argued, Amadeo was not a Freemason.

In 1869 Victor Emmanuel II then appointed a new ambassador in the person of his loyal general and senator Enrico Cialdini, who knew Spain well. In practice, he acted as the king's personal representative, who had been awarded the entire record of relations with Spain.

King of Spain (1871-1873)

Amadeo was the first king of Spain elected in a Parliament, which for the usual monarchists was a serious insult. On November 16, 1870, the deputies voted: 191 in favor of Amadeo de Saboya, 60 for the Federal Republic, 27 for the Duke of Montpensier, 8 for General Espartero, 2 for the unitary Republic, 2 for Alfonso de Borbón, 1 for an indefinite Republic and 1 for the Duchess of Montpensier, the Infanta María Luisa Fernanda, sister of Isabel II; there were 19 blank ballots. In this way the president of the Cortes, Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla, declared: «The Lord Duke of Aosta is elected King of the Spanish».

It had the systematic rejection of Carlists and Republicans, each for reasons inherent to their interests; but also from the Bourbon aristocracy, who saw him as an upstart foreigner, from the Church, for supporting the confiscations and for being the son of the monarch who had closed the Papal States; and also from the town, due to his lack of people skills and difficulty in learning the Spanish language.

Immediately, a parliamentary commission went to Florence to notify the duke; On December 4, he officially accepted this choice, embarking shortly after for Spain from the port of La Spezia. While Amadeo I was traveling to Madrid to take office from him, General Juan Prim, his main supporter, died on December 30 from injuries sustained in an attack three days earlier on Calle del Turco in Madrid.

Amadeo disembarked in Cartagena on December 30, to arrive in Madrid on January 2, 1871. There he went to the Basilica of Nuestra Señora de Atocha to pray before the corpse of Prim. After this bitter drink he moved to the Courts, where he took the mandatory oath: "I accept the Constitution and I swear to keep and keep the Laws of the Kingdom", ending the act with the solemn declaration by the president of the Courts: "The Courts have witnessed and heard the acceptance and oath that the King has just lent to the Constitution of the Spanish Nation and to the laws. He is proclaimed King of Spain Don Amadeo I ».

When Amadeo came to power, the only thing he achieved was to unite all the opposition, from Republicans to Carlists. As an example of this, it is enough to reproduce a few lines of the speech before the first Cortes of the new monarchy of the republican leader Emilio Castelar:

Given the state of opinion, Your Majesty must leave, as surely Leopoldo of Belgium had gone (sic, by Leopoldo of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen), lest it have an end similar to that of Maximilian I of Mexico...

Amadeo had great difficulties due to Spanish political instability. The government coalition that Juan Prim had raised had split after his death. The Liberal Union, except for Francisco Serrano and a small sector, embraced the still expectant Bourbon cause. The progressives had split into radicals, led by Ruiz Zorrilla, and constitutionalists, headed by Sagasta.There were six governments in the little more than two years that his reign lasted, with abstention growing more and more.

Assassination attempt (1872)

It was half past eleven at night on July 18 when Amadeo I and María Victoria dal Pozzo were preparing to return to the Royal Palace after one of their frequent outings through the streets of nineteenth-century Madrid. On this occasion, they were returning from take a walk through the Buen Retiro Gardens together with Brigadier Burgos, who accompanied them in the same carriage. That same day the kings and queens were already warned of the news indicating that attacks against them were going to be committed in the streets of Madrid, but the king, turning a deaf ear to the indications, said:

If I had to listen to all the threats, I couldn't go out and I would have been killed at least a dozen times. I don't want the people to say that the king is locked in his palace because he's afraid.

Inspector Joaquín Martí, who was in charge of the news about the attack, was in charge of organizing the measures to be carried out to prevent the attack. This is how he arranged agents of the public order body dressed in civilian clothes throughout the route that went from the Royal Palace to the Jardines del Buen Retiro, as well as a tavern located in the Plaza Mayor. It was from that same tavern that a group made up of about twenty men was seen leaving, who, upon reaching Calle del Arenal, broke up into groups of three and four people, distributing themselves between the Plaza de Oriente, the steps of the Plaza Prim, the Café de Levante, the church of San Ginés and the intersection between Calle Arenal and Puerta del Sol.

Once the uncovered carriage crossed the Puerta del Sol, around midnight, it headed down the famous Arenal street. It was near the current Plaza de Ópera where several men fired three times against the couple with blunderbuss and revolvers. Brigadier Burgos covered the queen with her body, while Amadeo I's response was to stand up while the coachman galloped off towards the Royal Palace.

Of the four attackers they were able to detain, one of them died from three shots fired by public order agents who were in the vicinity of Calle Arenal. He was around fifty years old, dressed poorly and was never able to identify him.One of the horses that pulled the carriage of the consorts also died on arrival at the Royal Palace after receiving three impacts.

Once they arrived at the Royal Palace and were safe, Amadeo I wanted to go out again to the place of the attack, but the pleas of the people who were around him at that moment prevented the idea. That same night, at half past one in the morning, the king sent a telegram to his father, Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, in which he said:

I inform you that we have been subjected to an attack tonight. Thank God we're safe.

The next day the king went back to Arenal street to inspect the place. There he was received by cheers and applause from among those who were in the place. All the parties, whatever their ideology, as well as the newspapers, condemned the attack. The newspaper El Combate, of republican and federal ideology, declared:

We strongly condemn the murder, and declare with allegiance that if the Republic did not have another way in Spain to be able that the way of the murder, we would completely renounce it, because the crime will always be anathematized by the truly revolutionary consciences.

The attack made the king gain popularity at times, even if it was temporary.

Last months of reign

After the assassination attempt against him, Amadeo I declared his anguish at the complications of Spanish politics «Ah, per Bacco, io non capisco niente. Siamo una gabbia di pazzi — I don't understand anything, this is a cage of madmen». The situation did not seem to improve, due to the outbreak of the Third Carlist War and the intensification of the Ten Years' War in Cuba. In addition, at the beginning of 1873, the government coalition, gripped by strong friction between the parties that made it up, definitively separated, running separately for the elections.

The icing on the cake was a conflict between Ruiz Zorrilla and the Artillery Corps. The president had expressed his firm decision to dissolve said military body, under threat of resigning, and the Army proposed to Amadeo I that he dispense with the Cortes and govern authoritarianly.

Madrid tradition asserts that at noon on February 11, 1873, King Amadeo I was informed of his "dismissal" while he was waiting for his meal in the Fornos café restaurant; He immediately canceled the request, asked for a grappa, picked up his family, renounced the throne and, without waiting for the authorization of the deputies (as required by article 74.7 of the 1869 Constitution), took refuge in the Italian embassy.

Amadeo wrote his resignation message, which was read by his wife. He did not address it to the president of the Council of Ministers, but to the representation of the Nation. He said like this:

To Congress:Great was the honor that I deserved the Spanish Nation choosing me to occupy your Throne; honor so much more for me appreciated, for she offered me surrounded by the difficulties and dangers that the company carries with it to govern such a country deeply disturbed. Encouraged, however, by the very resolution of my race, which first seeks avoids the danger; decided to inspire me only in the good of the country, and to place me by the top of all parties; determined to carry out the oath religiously for me promised to the Constituent Courts, and soon to make every line of sacrifices that give this courageous people the peace they need, the freedom they deserve and the greatness to that his glorious history and the virtue and constancy of his children give him right, believed that short experience of my life in the art of sending would be subject to the loyalty of my and that it would find powerful help to conjure the dangers and overcome the difficulties that were not hidden in my sight in the sympathy of all Spaniards, lovers of their homeland, eager to put an end to the bloody and sterile struggles They've torn their guts so long ago. I know you cheated on me. Two long years the Crown has to baby of Spain, and Spain lives in constant struggle, seeing the age of peace and venture that I long so earnestly. If they were strangers the enemies of their bliss, then, in front of these soldiers, as brave as they suffered, would be the first to fight them; but all with the sword, with the pen, with the word aggravate and perpetuate the evils of the Nation are Spaniards, all invoke the sweet name of the Homeland, all fight and they stir up for their good; and between the fat of the battle, between the confusing, the thundering, and contradictory clamor of the parties, among so many and so opposed manifestations of the public opinion, it is impossible to grasp what is true, and more impossible Find the remedy for bad sizes. I have eagerly sought him within the law and have not found him. Out of the law He must not look for it who promised to observe it. No one's going to slack my resolution. There would be no danger of me move to dissipate the Crown if I thought I was wearing it in my temples for the sake of the Spaniards did not cause mella in my spirit that ran the life of my august wife, at this solemn moment manifests, like me, the living desire that in his day pardon the perpetrators of that attack. But today I have the firm conviction that my efforts would be sterile and unreachable my purposes. These are, deputies, the reasons that move me to return to the Nation, and in his name to you, the Crown that offered me the national vote, making her renounce for me, for my sons and successors. Be sure that as I get out of the Crown I don't learn from love to this Spain as noble as misfortune, and that I bear no other sorrow than that of I could have taken care of all the good my loyal heart attached to her. Amadeo.

Palacio de Madrid to 11 February 1873.BOLAÑOS MEJÍAS, Carmen: The reign of Amadeo de Saboya and the constitutional monarchy. Madrid, UNED, 1999, pp. 238-239.

That same day, Congress and the Senate met in joint session to deliberate (in contravention of Article 47 of the Constitution). Emilio Castelar wrote the response of the National Assembly to the message of resignation from the Crown.

Sir:The sovereign courts of the Spanish Nation have heard with religious respect the in whose knightly words of righteousness, of honesty, of loyalty, have seen a new testimony of the high garments of intelligence and character that exalt V.M. and the love of the second country, which, generously and courageous, in love with their dignity until superstition and independence heroism, can't forget, no, that V.M. has been head of the state, personification of their sovereignty, first authority within their laws, and cannot be ignored honoring and exalting V.M. is honored and exalts itself. Lord, the Courts have been faithful to the mandate they brought from their electors and guardians of the legality they found established by the will of the Nation by the Constituent Assembly. In all its acts, in all its decisions, the Courts are they held within the limits of their prerogatives, and respected the authority of V.M. and the rights that by our constitutional pact to V.M. competed. Proclaim this very high and very clear, so that the responsibility of this conflict that we accept with pain, but that we will resolve with energy, the Courts unanimously declare that V.M. has been faithful, the most loyal keeper of respects because of the Chambers; faithful, most loyal keeper of the oaths rendered in the the moment when V.M. accepted from the hands of the people the Crown of Spain. Merit glorious, glorious in this time of ambitions and dictatorships, in which the blows of State and the prerogatives of absolute authority attract the most humble not yield to their temptations from the inaccessible heights of the Throne, to which they only arrive some privileged few of the earth. You can well say in the silence of your retreat, in the bosom of your beautiful Patria, in the home of his family, that if any human were able to attack the course of events, S.M., with its constitutional education, with its respect for the constituted right would have completed and absolutely attacked them. The Cuts, penetrated with such truth, would have done, to be in their hands, the elders sacrifices to get V.M. to withdraw from its resolution and withdraw its resignation. But the knowledge they have of the unshakable character of V.M.; the justice they have make the maturity of their ideas and the perseverance of their purposes, prevent the Courts beg V.M. to return to your agreement, and decide to notify you that they have assumed in itself the supreme power and sovereignty of the Nation to provide, in circumstances so critical and as quickly as you advise the grave of danger and the supreme of the situation, to save democracy, which is the basis of our policy, freedom, which is the soul of our right, the Nation, which is our immortal and Dear Mother, for which we are all determined to sacrifice effortlessly not only our individual ideas, but also our name and our existence. In more difficult circumstances our parents were found at the beginning of the century and they knew how to overcome them by inspiring in these lines and in these feelings. Abandoned by his Kings, invaded the paternal soil by strange hosts, threatened by that genius illustrious that seemed to have in itself the secret of destruction and war, Courts on an island where the nation seemed to end, not only saved the Homeland and wrote the epic of independence, but they created the ruins scattered from old societies the new society. These Courts know the Spanish nation has not degenerated, and hope not to degenerate themselves either the austere virtues that distinguished the founders of Spanish freedom. When the dangers are conjured; when the obstacles are overcome; when we get out of the difficulties it brings with it all times of transition and crisis, the Spanish people, that as long as V.M. remains on their noble soil must give all signs of respect, loyalty, consideration, because V.M. deserves it, because his most virtuous wife deserves it, because his innocent children deserve it, He will not be able to offer V.M. a Crown in the future; but he will offer another dignity, the dignity of a citizen within an independent and free people.

Palacio de las Cortes, 11 February 1873.FERNÁNDEZ-RÚA, José Luis: 1873. The first republic. Madrid, Thebes, 1975, pp. 231-233.

Despite Ruiz Zorrilla's attempts to ask for time to convince the monarch to return, an alliance between Republicans and part of the Radicals (majority) validated the resignation of the throne. That same afternoon of February 11, the First Spanish Republic was proclaimed.

During his brief reign, he hardly had any friends or confidants: his compatriot and personal secretary, the Marquis Giuseppe Dragonetti-Gorgoni, or his assistant, Emilio Díaz Moreu.

Return to Italy

Totally disgusted, after abdicating Amadeo moved to Lisbon accompanied by the head of the government and his last supporter, Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla, and from there he returned to Turin, his hometown, where he established his residence in the Palazzo Cisterna along with his wife and three children. There he resumed the title of Duke of Aosta, without holding any political office.

In 1876, his wife María Victoria fell ill with tuberculosis, a disease that caused her death on November 8, 1876. In the following years, the duke held representative positions under the reign of his brother, who in 1878 became King of Italy with the name of Umberto I.

After twelve years of widowhood, on September 11, 1888, he married in Turin the French princess Maria Leticia Bonaparte (Paris, November 20, 1866-Moncalieri, October 25, 1926), his niece and daughter of his sister María Clotilde de Saboya, with whom he had an only son.

Death and legacy

Two years after his second marriage, at the age of 44, Amadeo I died of pneumonia on January 18, 1890. His body rests in the royal crypt of the Basilica of Superga, in the hills outside from Turin. His friend Puccini composed in his memory the famous elegy for the string quartet Crisantemi .

Amadeo gave his name to Lake Amadeus in central Australia. Among the schools named after him, from the year of his death, and still in operation, the Amedeo di Savoia State Classical Secondary School in Tivoli is noteworthy. The city of Turin dedicated a central street and a hospital specializing in infectious diseases to him.

One of Amadeo's grandsons, Aimón, would reign briefly in Croatia between 1941 and 1943 as Tomislav II.

Offspring

Three children were born from his first marriage to Princess Maria Victoria dal Pozzo della Cisterna:

- Manuel Filiberto de Saboya-Aosta, II duke de Aosta (Genoa, 13 January 1869-Turin, 4 July 1931)

- Víctor Manuel de Saboya-Aosta, I conde de Turin (Turin, November 24, 1870-Brussels, October 19, 1946)

- Luis Amadeo de Saboya-Aosta, I duque de los Abruzos (Madrid, January 29, 1873-Jowhar, Italian Somalia, March 18, 1933)

From his second marriage to Princess María Leticia Bonaparte a boy was born:

- Humberto de Saboya-Aosta, I conde de Salemi (Turin, June 22, 1889-Crespano del Grappa, October 19, 1918).

Assessment

The Count of Romanones at the beginning of the XX century portrayed him thus:

From a spacious and somewhat prominent front, framed by curly scald; the black eyes, to look inexpressive; thick lips, dirty and white the teeth, the beard closed, concealing the prognatism of the Habsburgs... In the morals, he did not offer any outstanding traits, except for his well-tested personal value, free of ambition, fervent Catholic, having inherited from his father an impassioned inclination by the daughters of Eve.

The writer Eslava Galán in her 1995 Historia de España contada para scepticos describes the figure of Amadeo as follows:

Presence had Amazed, and bewildered in his uniform, with embroidery and charreteras, seemed like a figurine, but apart from the presence he was a man of scarce lights and, worst of all, dangerously gafe.Short space dedicated to the tragedy of a man who was called to be king of a country in which none of his subjects wanted to give him the least opportunity.

What can't be objected to is that he wasn't about to please. On a chariot ride in Madrid, the secretary and cicerone accompanying him told him that they were passing by the house of Cervantes and he answered without immuting: “Even though I have not come to see me, I will soon greet him.” To see the evil of the people, based on this fact, some detractors propose that he was a man of few letters. It could be replicated that almost all the kings of Spain have been and this has not prevented them from reigning, but in the case of Amadeo, it is false, since he was very fond of French pornographic novels.Eslava Galán (1995, p. 337)

In fiction

- In 2014 the director Luis Miñarro released his film entitled Stella cadente (Missing Star), based on the life of the kings Amadeo and Maria Victoria of Spain. The role of Amadeo was played by the actor Àlex Brendemühl.

Honorary Distinctions

Military

- Gold Medal to Military Value (Italy)

- Medal commemorative of the Italian Unification (Italy)

- Conmemorative Medal of the War of Independence Campaign (Italy)

Orders

- Grand Master of the Insigne Order of the Golden Toy "de facto" (Spain, 1870)

- Grand Master of the Royal and Distinguished Order of Carlos III (Spain, 1870)

- Grand Master of the Royal Order of Isabel la Católica (Spain, 1870)

- Grand Master of the Order of Military Merit (Spain, 1870)

- Grand Master of the Royal Military Order of San Fernando (Spain, 1870)

- Grand Master of the Order of San Hermenegildo (Spain, 1870)

- Master of the Order of Montesa (Spain, 1870)

- Master of the Order of Alcántara (Spain, 1870)

- Master of the Order of Calatrava (Spain, 1870)

- Master of the Order of Santiago (Spain, 1870)

- Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation (Italy, 1862)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Mauritius and Lazarus (Italy, 1862)

- Knight of the Order of the Elephant (Denmark, 1863)

- Knight of the Most Noble Order of the Jarretera (United Kingdom)

- Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle (Prussia)

- Knight of the Order of St. Huberto (Baviera)

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Amadeo I of Spain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Patrilineal Descent

- Humberto I, I count of Saboya (hacia 980-1047)

- Oton I, III count of Saboya (1023-1057)

- Amadeo II, V count of Saboya (1046-1080)

- Humberto II, VI count of Saboya (1065-1103)

- Amadeo III, VII count of Saboya (1087-1148)

- Humberto III, VIII count of Saboya (1136-1189)

- Thomas I, IX count of Saboya (1177-1233)

- Thomas II, XI count of Saboya (1199-1259)

- Amadeo V, XV count of Saboya (1249-1323)

- Aimón, XVII count of Saboya (1291-1343)

- Amadeo VI, XVIII count of Saboya (1334-1383)

- Amadeo VII, XIX count of Saboya (1360-1391)

- Amadeo VIII (antipa Félix V), XX count of Saboya, I duke of Saboya, Prince of Piedmont (1383-1451)

- Louis, II Duke of Saboya, Prince of Piedmont (1413-1465)

- Philip II, VII Duke of Savoy, Prince of Piedmont (1443-1497)

- Charles II, IX Duke of Saboya, Prince of Piedmont (1486-1553)

- Manuel Filiberto I, X duke de Saboya, Prince of Piedmont (1528-1580)

- Carlos Manuel I, XI Duke of Saboya, Prince of Piedmont (1562-1630)

- Tomás Francisco, I Prince of Carignano (1596-1656)

- Manuel Filiberto II, II Prince of Carignano (1628-1709)

- Victor Amadeo I, III Prince of Carignano (1690-1741)

- Luis Víctor, IV Prince of Carignano (1721-1778)

- Victor Amadeo II, V Prince of Carignano (1743-1780)

- Carlos Manuel, VI Prince of Carignano (1770-1800)

- Charles Alberto, VII Prince of Carignano and King of Sardinia (1798-1849)

- Victor Manuel II, King of Sardinia and King of Italy (1820-1878)

- Amadeo I, King of Spain and Duke of Aosta (1845-1890)