Alteration (music)

The alterations or accidents, in music, are the signs that modify the intonation (or pitch) of natural and altered sounds. The most used accidentals are the sharp, the flat and the becuadro.

Alterations and their effects

- Sustained: raises the sound a chromatic semitone. It is represented with the sign ▪.

- The bemol: lowers the sound a chromatic semitone. It is represented with the sign ♫.

- The box: cancels the effect of the other alterations. It is represented with the sign ▪.

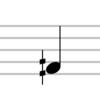

- The double held: makes the sound rise a tone. It is represented with the sign

.

. - The double bemol: makes the sound down a tone. It is represented with the sign

.

.

formerly the double becuadro was also used, but it has fallen into disuse within western music.

Some musical systems other than the Western musical system also use half-sharp, half-flat, half-sharp, and half-flat.

|

Typologies

Own accidentals

The proper accidentals are those that are placed in the key signature, after the clef and before the time signature. They are part of the key signature and are also called key signature. They alter all the sounds of the same name found in a piece of music, thus defining the tonality.

The key signature accidentals always appear in a certain order, which varies depending on whether they are flats or sharps. The order of the flats is the reverse of that of the sharps and vice versa. In the Latin system of notation they are:

- Order of the bemoles: yes - mi - la - re - sol - do - fa

- Order of the sustained: fa - do - sun - re - la - mi - yes

In alphabetic or Anglo-Saxon notation it is the same order, but when using different letters the combination has given rise to a mnemonic rule through the formation of the following acrostics:

- B - E ending - A ending - D ending - G ending - C ending - Battle Ends And Down Goes CMake them Father.

- F - C index - G destined - D destined Father Cmake them Goes Down And Ends Battle.

Accidental Alterations

An accidental is one that is placed anywhere in the score to the left of the notehead it affects.

Alters the musical note before the one written, as well as all the notes of the same name and pitch that are in the measure where it is. That is, it affects all the same sounds to the right of the accidental up to the next barline. Accidentals do not affect the same note in a different octave, unless indicated in the key signature.

If that same note should again carry an accidental beyond the barline, that accidental must be repeated in each new measure that is necessary.

This type of accidentals is not repeated for repeated notes unless one or more different pitches or rests are involved. They are also not repeated in tied notes unless the slur is moved from line to line or page to page.

Because seven of the twelve notes of the equal temperament chromatic scale are natural, (the piano's "white keys" do, re, mi, fa, sol, la and si), this system helps to significantly reduce the number of accidentals required for the musical notation of a passage.

Note that in some cases the accidental can change the pitch of the note by more than a semitone. For example, if a sharp G is followed in the same bar by a flat G, the flat symbol on the last note means that it will be two semitones lower than if it were not. there would be no change. In such a way that the effect of the alteration must be understood in relation to the "natural" intonation derived from the location of the note on the staff.

For the sake of clarity, some composers place a becuadro before the accidental. So, if in this example the composer actually wanted the note a semitone lower than the natural g , he could first put a becuadro sign to cancel the previous g sharp. and then the flat. However, in most contexts, an f sharp could be used instead.

Courtesy or Cautionary Alterations

The courtesy or precautionary accidentals are those that, although they are unnecessary, are placed to avoid reading errors. The barline is now understood to cancel the effect of an accidental (except in the case of tied notes). However, if the same note appears in the next bar, editors often use the courtesy accidental as a reminder of the correct tuning of that note. The use of courtesy accidentals varies, but is considered mandatory in some situations such as the following:

- When the first note of a compass is affected by an alteration that has been applied in the previous compass.

- When, after a ligature that carries the effect of the alteration beyond the bar of compass, the same note appears again in the next compass.

There are other possible uses but they are applied in a non-consistent way. Courtesy accidentals are sometimes enclosed in parentheses to emphasize their reminder nature. Courtesy accidentals can be used to clarify ambiguities, but they should be kept to a minimum.

While this tradition still holds true especially in tonal music, it can be cumbersome in other types of music that feature frequent accidentals, such as atonal music or jazz. Consequently, an alternative system of note-for-note accidentals has been adopted with the aim of reducing the number of accidentals that need to be notated in a bar.

Single and double accidentals

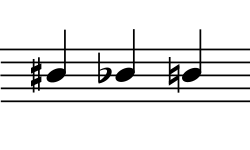

- The simple alteration is the one that alters, increasing or reducing, the sound in a chromatic semitone. They are sustained and bemol (see Figure 1).

- The double alteration is the one that alters, increasing or reducing, the sound in two chromatic semitones. («'Double Sharp'

)—raises the pitch two half steps. 'Double Flat'

)—raises the pitch two half steps. 'Double Flat' ) - lowers the pitch two half steps»). They are the double sustained and the double bemol (see Figure 2). There was also a double box, but it has fallen into disuse. This type of alteration is due to an innovation developed at the beginning of 1615.

) - lowers the pitch two half steps»). They are the double sustained and the double bemol (see Figure 2). There was also a double box, but it has fallen into disuse. This type of alteration is due to an innovation developed at the beginning of 1615.

- A Fa to which a double-held is applied raises an entire tone so it is enharmonicly equivalent to a Sun. The use of double alterations varies depending on how to score the situation in which a double-held note is followed in the same compass by a note with a simple hold. Some publications simply use a single alteration for the last note, while others use a combination of a bench and a sustained one, understanding that the bench only applies to the second supported.

- Double alteration with respect to a specific tonality, raises or lowers the notes containing a sustained or bemol in a semitone. For example, when in the tonality of do held minor or my greatest fa, do, sun and re contain a sustained, the addition of a double alteration (sustained dose) to fa, for example, in this case would only raise the support already contained in the note fa half tone, giving rise to a Sun natural. Conversely, if a double has been added to any other note that does not contain a supported or bemol indicated by the armor, then the note will be increased in two semitones or an integer tone regarding the chromatic scale. For example, in the armor mentioned any note that is not fa, do, sun and re will increase in two semitones instead of one, so one the double held raises the note the to its enarmonic equivalent Yeah..

Ascending and descending accidentals

- The upward alteration is the one that increases the sound in a chromatic semitone. It's sustained.

- The descending alteration is the one that reduces the sound in a chromatic semitone. It's the bemol.

The only alteration that can be both ascending and descending is the becuadro.

History of accidental notation

The three main alteration symbols are derived from variants of the lowercase letter b: the sharp signs (♯) and the becuadro (♮) of the square form of «b quadratum» or «b durum» and the flat sign (♭) of the rounded form of «b rotundum » or «b molle» (see Figure 3).

In the early days of European musical notation (with tetragram-based Gregorian chant manuscripts), only the note “b” (Si) could be altered. It could be a flat, therefore passing from the “hexachordum durum” or hard hexachord (Sol-La-Si-Do-Re-Mi) where the Si is natural, to the «hexachordum molle» or soft hexachord (Fa-G-La-Si♭-Do-Re), where the Si is flat. The note b is not present in the third hexachord “hexachordum naturale” or natural hexachord (Do-Re-Mi-Fa-Sol-La).

This prolonged use of b (Si) as the only alterable note helps explain some peculiarities of the notation:

- The bemol sign ♫ actually derives from a letter b which refers to the note b (Yeah.) of the mild hexacordo or Yes, bemol.which in origin meant exclusively Yes, bemol.;

- The sign of the box ▪ and the ▪ come from a letter b with square shape, which refers to the note b (Yeah.) of the hard hexacordo or Naturalwhich in origin meant exclusively Natural.

Many languages have maintained this etymology in the terms to designate these musical alterations. Thus, for example, it is called “Flat” in Spanish, Galician, Basque, Portuguese and Polish; «bémol» in French, «bemolle» in Italian or «bemoll» in Catalan.

“Becuadro” in Spanish and Galician; “bequadro” in Italian and Portuguese; “bécarre” in French or “becaire” in Catalan. Along the same lines, in German musical notation the letter B designates B flat while the letter H, which is actually a deformation of the b square, is used to designate B natural.

The exception is the English language which calls flat «flat», which means 'flat', 'flat', and flat «natural», which means 'natural', 'unaltered'.

As polyphony became more complex, notes other than B had to be altered in order to avoid undesirable harmonic or melodic intervals (especially the augmented fourth or tritone, to which theorists of music they referred to as "Diabolus in Musica", that is, 'the devil in music'). The sharp was first used on the note fa♯, then came the second flat on the note mi♭, later do♯, sol♯, etc.

Circa 16th century si♭, my♭, la♭, re♭, sol♭ and fa♯, do♯, sol♯, re♯ and la♯ were in use to a greater or lesser extent.

However, these accidentals were often not noted in vocal sheet music books. While in the tablatures the precise and correct heights of the notes were always noted. The notational practice of not signaling implied accidentals, letting them be played by the performer instead, is called musica ficta, which means fake music.

Strictly speaking, the medieval signs ♮ and ♭ indicate that the melody is progressing within a (fictitious) hexachord of which the affected musical note is the e or the fa respectively. This means that they refer to a group of notes "around" the pointed note, rather than indicating that the pointed note itself is necessarily an accidental. Sometimes it is possible to see an my font (♮) associated with a re for example. This could mean that the re is just a re, but the previous note mi is now a fa, it is that is, it is an A that goes down to E flat (the one we know as "alteration" in the current system).

Microtonal notation

Composers of microtonal music have developed a number of notations to indicate the various pitches outside of standard notation. One of these notation systems to reflect quarter tones is the one used by the Czech Alois Hába and other composers (see Figure 4).

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, when Turkish musicians changed their traditional notation systems - which were not based on staves - to the European system based on staves, they made an improvement on the European system of accidentals to in order for him to be able to notate Turkish musical scales that make use of intervals smaller than the tempered semitone. There are various systems of this type that vary in terms of the division of the octave that they propose or simply in the graphic form of the alterations. The most widespread method (created by Rauf Yekta Bey) uses a system of 4 sharps (about +25 cents, +75 cents, +125 cents, and +175 cents) and 4 flats (about −25 cents, −75 cents, −125 cents and −175 cents), neither of which correspond to sharp or flat tempered. They assume a Pythagorean division of the octave taking the Pythagorean comma as the basic interval (about one octave of the tempered system, actually closer to 24 cents, which is defined as the difference between 7 octaves and 12 fifths in perfect tuning). Turkish systems have also been adopted by some Arab musicians.

Ben Johnston created a system of notation for pieces in just temperament, where the just major chords of C, Fa and G (4:5:6) and the Accidentals are used to apply just the right tuning in other keys.

Between 2000 and 2003, Wolfgang von Schweinitz and Marc Sabat developed the Helmholtz-Ellis extended just intonation system JI (Just Intonation), a modern adaptation and extension from the principles of notation first used by Hermann von Helmholtz, Arthur von Oettingen, and Alexander John Ellis, which quickly began to be adopted by musicians working in the field of accidental-extended just intonation.

Notation, reading and music theory

In musical notation, accidentals are placed to the left of the oval of the figure that represents the sound being altered. On the other hand, in the reading, the accidental must be said after the name of the sound, for example: do sharp. In music theory, accidentals should not be pronounced.

Contenido relacionado

Miyamoto Musashi

Chilean coat of arms

Fito paez