Altarpiece

The altarpiece is the architectural, pictorial and sculptural structure that is located behind the altar in Catholic churches of the Latin rite; in oriental churches in communion with Rome or not, there is no similar function, given the presence of the iconostasis, and in Protestants a great reduction in decoration is usually chosen. The word derives from the Latin expression retro tabula (lit., 'after the altar'). To designate the same term, the expression " altar piece" (more typical of the English language –altarpiece–, where retable is distinguished from reredos) or the Italian pala d'altare (or ancóna).

Introduction

The name of high altarpiece refers particularly to the one that presides over the main altar of a church; given that the churches can have other altarpieces located after the altars of each one of the chapels. The term "table" refers to the support of the paintings (which can also be the canvas), and its structure is indicated with the terms diptych, triptych or polyptych (a layout that can also have smaller-format devotional works not intended for an altar, such as The Garden of Earthly Delights).

The altarpieces have been made with all kinds of materials (all kinds of wood, all kinds of stones, all kinds of metals, enamel, terracotta, stucco, etc.) and can be sculptural (in different degrees of relief or with round figures), or pictorial; It is also very frequent that they are mixed, combining paintings and carvings.

Since the end of the XIII century they were the most relevant elements in the interior decoration of churches, both in Northern Europe (Germany and Flanders; a specific typology is called the "Antwerp altarpieces") as well as in the south (Italy, and especially in the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula, where altarpieces achieved extraordinary development, later spreading throughout the Spanish-Portuguese colonies in America and Asia). The preference for this artistic form meant that in many cases they were hidden behind earlier Romanesque frescoes.

Architects, sculptors, potters, gilders, carpenters and carvers collaborated in those of great complexity, so their production was an expensive and slow process, especially in the largest specimens. Its state of conservation has depended on multiple factors, among which are the well-intentioned attacks to which they have been subjected for centuries (inadequate cleaning and "beautification"), looting or destruction in contexts of war or conflict of a very different kind, and deterioration due to adverse physical conditions. Consequently, its restoration is equally problematic and specialized.

Altarpieces usually adopt a geometric layout, divided into «bodies» (horizontal sections, separated by moldings) and «streets» (vertical sections, separated by pilasters or columns). The units formed by this grid of bodies and streets are called "encasamentos", and usually house sculptural representations or paintings. The set of architectural elements that frame and divide the altarpiece is called "mazonería". There are also examples that are organized in a simpler way, with a single scene focusing the attention.

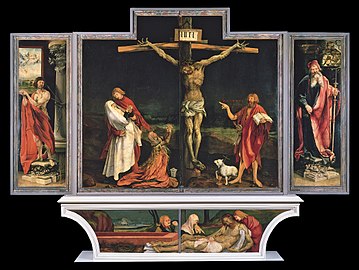

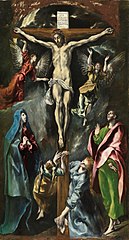

The altarpiece is usually raised on a plinth to avoid moisture from the ground. The lower part that rests on the plinth is called a bench or predella, and it is arranged as a horizontal section as a frieze that in turn can be divided into compartments and decorated. The element that finishes off the entire structure can be a semicircular lunette or a "thorn" or attic; as corresponds to its dominant position, it is usually reserved for the representation of the Eternal Father or a Calvary. The whole set is sometimes protected with a molding called dust cover, very common in Gothic altarpieces. The articulated altarpieces (a common characteristic in the notable Flemish altarpieces that achieved great influence in Italy —Portinari triptych— and in Spain —Hispanic-Flemish style—) allowed to present two arrangements: open and closed, although sometimes the complexity is greater (altar of Isenheim). The "closed" position of Flemish altarpieces used to contain grisailles (a pictorial representation that simulates stone sculptures using a trompe l'oeil). The articulation of the altarpieces gave rise to the German name flügelaltar (literally "altar of wings").

From the XV century, the tabernacle or tabernacle (place where the sacred forms are kept) became relevant, gradually centralized the space of the altarpiece to become, on occasions, its main element, even adopting free-standing and independent forms.

The Protestant Reformation of the XVI century, characterized by a marked aniconism, which in some cases led to iconoclasm (with greater intensity in Anabaptism and Calvinism, less in Lutheranism, minimal in Anglicanism, where the use of altarpieces is explicitly authorized), practically eliminated the use of altarpieces and sacred images in the territories that led the movement (North Germany, Switzerland, Holland, England, Scandinavia). In some cases magnificent examples of earlier times have disappeared; while the imagery and altarpiece tradition was substantially limited to Catholic countries, where it even intensified as a consequence of the Counter-Reformation.

Altarpiece as a serialized narrative representation and as a stage

In the performing arts, "retablo" is the small stage on which the puppet theater is performed. Significantly, the DRAE derives this use ("small stage in which an action was represented using figurines or puppets", meaning 3) from its peculiar way of defining pictorial-sculptural altarpieces, where it emphasizes its capacity for narrative representation. serialized ("set or collection of painted or carved figures, which serially represent a story or event", meaning 1) rather than in its decorative capacity ("work of architecture, made of stone, wood or other material, which makes up the decoration of an altar", meaning 2). The so-called "hallelujahs" were also a similar literary form, associated with popular representations (such as their recitation by the blind or other kinds of beggars, while pointing to the drawings that illustrate what was recited in the form of vignettes, a precedent of the comic).

Cervantes refers to this theatrical form on two occasions: in El retablo de las maravillas (entremés from 1615) and in chapters XXV and XXVI of the second part of Don Quixote de la Mancha (published the same year).

Manuel de Falla composed El retablo de Maese Pedro (1923) about the Quixotic episode.

With the name «Spanish theatrical altarpiece», reference is made not so much to a dramatic genre but to the way of conceiving the theater itself by the authors of the Spanish classical theater of the Golden Age (particularly Calderón, La vida es dream, The great theater of the world).

The component of «pretending reality» that the theatrical altarpieces have in Cervantes or Calderonian works («to deceive with the truth» and «to teach with deceit») is also present in the role that is expected of the altarpieces ecclesiastics (defined as "illusory machines") in the "control over the sensibility of the faithful", configuring "the theatrical stage of the liturgy, dogma, piety and Catholic devotion". Such a condition makes them particularly useful not only for iconographic and iconological studies, but for the history of mentalities and anthropology.

Precedents

The altar was, from the first moments of Christianity, the central element of the liturgy. At first its layout in the temple was free-standing and central, with the faithful located around it, thus recalling the banquet of the Last Supper. However, with the strengthening of the authority of the clergy, the altars gradually moved to the presbytery, a high place inaccessible to the faithful, close to the wall at the head of the church (apse), and which in certain types of church remained even hidden with curtains, bars, or with the iconostasis. The officiant performed most of the ritual with his back to the faithful.

The early Christian temples decorated their interiors with mural paintings (Dura Europos chapel) and certain objects for liturgical use, such as reliquaries, chests, ivory diptychs or small statues. Its primitive austerity was compensated with the lavish donations offered by the potentates (Guarrazar's treasury). In the Pre-Romanesque, images of the crucified Christ began to spread, which were placed hanging from the walls or the ceiling, and which could be pictorial or sculptural (Crucified of Gero, Cologne Cathedral), or dispensing with the occasions for figuration to take the form of a jewel (crux gemmata, such as the Victory Cross of the Holy Chamber of Oviedo). The decoration of the antependium (pallium altaris, frontal or front of altar) also took on a lot of relevance, derived from the curtains that covered the urns with relics arranged under the altar table (whose color had to vary to correspond to the liturgical color of the feast or office of the day) and which were enriched with all kinds of ornaments in precious materials. The hypothesis has been proposed that, evolutionarily, the altarpiece derived from the antependium .

Some structures derived from the classic aedicula (aedicules -"templates" or "small buildings"-), also seem to prefigure the shapes of the later altarpiece, especially the ciborium or ciborium (a fixed canopy or canopy supported by four columns, later called a canopy or canopy), a common element in early Christian churches, which protected and gave visual relevance to the altars, reliquaries and tombs of saints and martyrs, which usually coincided in the same place.

The internal decoration of the churches was adapted to their modest dimensions in most cases, and the accent was placed on wall decoration, either through brightly colored frescoes, or with mosaics enriched with gold tesserae (very common in Byzantine art), so that the images would stand out in generally dark and reduced interiors. The elements that were located on the altar were almost always furniture (chests, diptychs, icons) and their sumptuousness in terms of materials also meant a small size. The Romanesque did not bring about a great change in this simple system of interior decoration of the temples, with a predominance of frescoes in the apses (Romanesque churches of the Bohí Valley, Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe abbey), the figures of Christ in Majesty and Virgin in Majesty and the altar frontals, which became painted, carved or embossed decorative supports, often enriched with enamels or gold work. Although the shapes and materials were already very similar to those of later altarpieces, the The arrangement of the piece was exactly the opposite (in front of the altar and under it, instead of behind and in an elevated position). In fact, some have been reused as altarpieces, such as the one in the sanctuary of San Miguel de Aralar.

Gothic altarpiece

The splendor of monasticism, the strength of cities and the population and economic growth that occurred in Europe from the XIth century made temples have to adapt in order to accommodate a larger number of faithful, satisfy the desires of elite patronage and show the wealth of a society in which religion governed all aspects of life. From the XII century, Gothic art arose; architecture acquires colossal dimensions and great constructive complexity, and both painting and sculpture, at the request of a society that loves luxury and ostentation, are greatly developed. Another factor of change was the appearance of the mendicant orders, which advocated a more emotional religiosity close to the faithful, while at the same time being concerned with teaching and doctrine.

As in the Romanesque, great narrative cycles continued to be carved on the portals of churches and cathedrals; but the interior decoration will undergo a major transformation: the stained glass windows, which occupy the large openings in the walls thanks to the new construction techniques, are illustrated with sacred representations; and the new amplitude and luminosity of the temples allows the better contemplation of the images distributed by the numerous naves and chapels, which fulfilled the function of corporate spaces for the institutions that commissioned them (guilds, brotherhoods and aristocratic families), converted into artistic patrons.

New pious practices required an increasing number of increasingly sumptuous and visible sacred objects. The cult of relics and images of saints, considered a valuable instrument for evangelization, intensified.

It is in this context that the first altarpieces arose, first as rectangular tables with images of modest size (such as the Westminster altarpiece, 1x3 meters, or the Barnabas altarpiece, 1x1.5 meters), sometimes matching with an altar front (as in one of the oldest preserved examples: that of the church of the monastery of Santa María de Mave, Palencia), later articulated and folding, in an increasingly complex way (diptychs, triptychs, polyptychs such as the so-called Polyptych of Ghent), or made with precious materials (those of the cathedral of Girona, the altare argenteo di San Jacopo of the cathedral of Pistoia or the Pala d'Oro of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice).

At first, the altarpieces did not completely abandon their movable or folding character, and it is possible that many were used in processions and other types of public events that required their transfer outside the temple area, as was the case with the diptychs devotional or icons of a domestic and private nature. However, little by little the altarpieces became larger and more stable, since they almost always had to stand out in the colossal dimensions of abbeys or cathedrals. Altarpieces were consolidated throughout Latin Christianity in the Late Middle Ages (a vast space —from Iceland to Cyprus— covered by multiple connections and mutual influences and local variants, from the Italian pala to the flügelaltar central Europe) as a thriving and creative artistic genre, which had important artists specialized in the different specialties necessary for its design and execution.

The most common material used was wood, almost always gilded and polychrome, although there are plenty of examples in exposed wood or other materials (silver or all kinds of stones). Regional variants make uniform classification difficult; For example, in Aragon, from the XIV century they took on a peculiar form of Eucharistic display, almost always made of alabaster. The Gothic altarpiece usually presents a markedly geometric appearance, with the encasamentos linearly arranged and occupied by paintings or sculptures. Many of them take the shape of the apse in which they are located (such as the largest in the Old Cathedral of Salamanca), although the quadrangular scheme with a projection at the top as a finish (the thorn or attic) is more common. which initially took the form of one or more gables. The outline of the altarpiece used to be traversed by a very prominent molding (the dust cover). The decorative elements of Gothic architecture were abundantly used, framing the figures (whether they were paintings, reliefs or bulk images) by means of canopies or chambranas, and pinnacles, crests, rosettes and other elements occupying the rest of the space, as a result of the horror vacui. The introduction of heraldic elements or even portraits of the principals (usually in a praying position) was also common. Over time, the separation between the body of the altarpiece itself and the bench or predella on which it rests was established; and within that, the configuration in bodies and streets. The altarpieces gained in size, complexity and luxury, until they became huge, profusely decorated structures. They were ideal for the narration of the cycles of the life of Christ, the Virgin or the saint to whom the altar was dedicated. The presence of numerous images, dedications or relics within the same temple justified the multiplication of chapels, altars and altarpieces. The one in the main chapel or presbytery, the main focus of attraction, is called the "high altarpiece", while those located along the side walls, transept and ambulatory are called "lateral altarpieces" or "minor altarpieces".

Altarpiece-facades

The altarpiece of the XV and XVI reached an extraordinary development in the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula, where the general characteristics of the Gothic style were added to those specific to both Flemish Gothic (commercial and political relations with Flanders were especially intense) and Italian Gothic on the other, and the local influences of Mudejar art. The architecture itself reflects the importance that the altarpieces had reached, by projecting the conventions of their design on the main facades of the temples (and even other types of buildings), with the typology called «facade-altarpiece» (not to be confused with a confluent concept, that of façade-curtain), which lasted in the Spanish architecture of the Renaissance and the Baroque and the colonial architecture of America. For the new conception of the portals, the key moment was the overcoming of the classical Romanesque and Gothic conception of flared portals with archivolts and tympanums with sculptural decoration, which was substantially altered in the Hispano-Flemish architecture of the second half of the century XV.

Gothic altarpieces in the Iberian Peninsula

Among the surviving examples, few remain in their original location. Much of it has been transferred to diocesan and provincial museums, and some of the most important have become part of the collections of the National Sculpture Museum (Valladolid), the National Art Museum of Catalonia (Barcelona) or the Prado Museum. (Madrid). Very notable have been the temporary exhibitions of the cycle The Ages of Man. As a result of the plundering of Spanish artistic heritage (very intense between 1808 and the mid-XX century) many Gothic altarpieces have ended up in collections individuals and in foreign museums. In the past, it is common for them to have suffered all kinds of alterations when they were disassembled for different reasons, frequently as a consequence of their replacement by Renaissance or Baroque altarpieces, and for their reuse in environments other than those for which they were initially designed. All this has produced that most of them are dispersed or have been totally or partially lost. The documentary sources written for these times (relatively abundant in the Spanish archives compared to other cases) make it possible to reconstruct the history of a good number of altarpieces, but it is most likely that for the vast majority there will not even be any news. of its existence. They stand out, in chronological order:

- The main altarpiece of the cathedral of Gerona, made in silver, forming twenty-six compartments with relief figures, of the centuryXIV.

- The old altarpiece of the cathedral of Barcelona, of fundamentally architectural structure (1356-1367, modified in the centuries XV and XVI His central image, an apostle James, was added when the altarpiece was moved to the church of San Jaume in the same city, in 1971-).

- The altarpiece of San CristobalXIV), coming from a Rioja monastery.

- The altarpiece of Santo Domingo de Tamarite de Litera (second third of the century)XIV).

- Due to the Master of Estimariu or of Estopiñán (at the Crown of Aragon between 1360 and 1380, whose identity and origin is subject to debate), such as the altarpiece of Saint Vincent and the tables of Saint Lucia.

- The dues to Andrés Marzal de Sax (Marçal de Sas, probably from Saxony), introduction of the international Gothic Central European in Spain (active in Valencia between 1393 and 1410). He is traditionally attributed to the Great altarpiece of St. George painted for the Brotherhood of the Centenary of the Ploma, although at present the attribution is discussed, having to be assigned to a Master of Centenar.

- Due to Pere Serra, as the altarpiece of the Holy Spirit of the Seu of Manresa (ca. 1394) and the altarpiece of All Saints of the Monastery of Sant Cugat (1375).

- The Quejana altarpiece (1397).

- The dues to Gherardo Starnina (the altarpiece of the chapel of the Saviour of the Cathedral of Toledo of 1395, and the altarpiece of Fray Bonifacio Ferrer, Valencia of 1398-1401).

- Gothic altarpieces on the Iberian peninsula (s.XIV)

- The altarpiece of Archbishop Don Sancho de Rojas (1415-1420), from the Monastery of St Benito de Valladolid, attributed to Juan Rodríguez de Toledo (who probably received the influence of Italian painters such as Starnina).

- The main altarpiece of the Old Cathedral of Salamanca, Nicolás Florentino and Dello Delli (1430-1450).

- The old altarpiece of the cathedral of León, today dismantled, by Nicholas French (ca. 1434).

- El retablo mayor de la Seo (Zaragoza, 1434-1480), by Pere Johan and Hans de Suabia, carved in alabaster.

- Due to Bernat Martorell, who developed extensive retablistic work in the mid-centuryXV (Transfiguration altarpiece of Barcelona Cathedral, Retablo of the Saint Johns Vinaixa, Retablo de San Miguel of the Pobla de Cervoles, Retablo de San Pedro Púbol, altarpiece of Saint Mary Magdalene Perella, Retablo de San Vicente of Menàrguens, etc.)

- The altarpiece of the chapel of the House of Barcelona City, the painter Lluis Dalmau and the carpenter Francesc Gomar (1443-1445). Only the main panel, called Virgen dels Consellers.

- The altarpiece of Peralta de la Sal (1450-1456), by Jaume Ferrer II and Pedro García de Benavarre, interpreted as a transition between the international Gothic and the influence of the Flemish primitives (in particular Robert Campin).

- Gothic altarpieces on the Iberian peninsula (1.a half s.XV)

- Due to Nuno Gonçalves ("paneles de Avis" or "de San Vicente de Fora", ca. 1470) and so-called "Portuguese primaries" (see also Portuguese Gothic#Pintura).

- The altarpiece of the church of Santo Domingo de Silos de Daroca, with central board of Bartolomé Bermejo and the rest of Martin Bernat (1474-1477). Currently dismantled, the Bermejo table is one of the most outstanding works of the Museo del Prado.

- The dues of Fernando Gallego, who developed extensive retablistic work at the end of the centuryXV (restalls of Zamora Cathedral -the altarpiece of San Ildefonso and the main altarpiece, today distributed in the "tablas de Arcenillas"-, altarpiece of the Cathedral of Ciudad Rodrigo, altarpiece of Santa María la Mayor de Trujillo, altarpiece of the church of the Asunción de El Campo de Peñaranda, etc.)

- The main altarpiece of the cathedral of Seville, considered one of the greatest of Christianity, made in a dilated period (between 1482 and 1564) by Pedro Dancart, Master Marco, Pedro Millán, Jorge Fernández, Roque Balduque, Juan Bautista Vázquez el Viejo and Pedro de Heredia.

- The altarpiece, oratory or polyptic of Isabella the Catholic (ca. 1496-1504), by Juan de Flandes and Michael Sittow (ca.Melchior German), a portable devotional altarpiece, today dismantled, of which twenty-eight tables of the original forty-seven were preserved, where the cycle of the lives of the Virgin and Christ was developed.

- The main altarpiece of the Miraflores Carthus (Burgos) by Gil de Siloé (1496-1499).

- Gothic altarpieces on the Iberian peninsula (2.a half s.XV)

- The main altarpiece of the cathedral of Toledo, where Felipe Bigarny, Sebastián de Almonacid, Petit Juan or Juan de Borgoña (1497-1504). The new incorporation of the transparent or camarin, formula of great subsequent success.* The main altarpiece of the cathedral of Ávila (1499-1508), where Pedro Berruguete, Juan de Borgoña or the then young Vasco de Zarza intervened. Curiously, years later, in 1525, Zarza held together with the young Alonso Berruguete (son of Peter) the main altarpiece of the monastery of the Improving of Olmedo, already with Renaissance criteria.

- The main altarpiece of Oviedo Cathedral, performed by a team of artists led by Giralte in Brussels (1512-1517).

- The main altarpiece of the Basilica of Lequeitio, of unknown sculptor (probably of the Spanish-Plamenic circle of Gil de Siloé and Alejo de Vahía), gold and polychrome of Juan García Crisal (1514).

- The main altarpiece of the Cathedral of Orense, by Cornelis of the Netherlands (the beginning of the centuryXVI).

- Gothic altarpieces on the Iberian peninsula (s.XVI)

Gothic altarpieces in Central-Western Europe

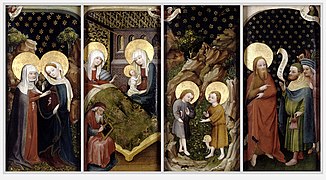

The areas politically divided between the kingdom of France, the Burgundian State and the principalities of the Holy German Empire developed an important production of Gothic altarpieces in the last centuries of the Middle Ages, stylistically labeled with the different denominations of late Gothic; Outstandingly the International Gothic, characterized by refinement, elegance and sentimentality, slender proportions, sinuous lines and colorful nuances that allow shading and volume to be given to the figures (painters such as Conrad Soest, Master Francke, Stefan Lochner, Henri Bellechose, Jean Malouel, Jean de Beaumetz, etc.), with influence also in areas further away from Central Europe, such as Italy or Spain.

Within this style, in the Bohemia of the XIV century, the work of two anonymous masters stood out, respectively authors of the Altarpiece from Vyšší Brod or Hohenfurth, which represents the childhood of Christ (Cistercian convent of Vyšší Brod or Hohenfurth, of the so-called Master of Vyšší Brod or Hohenfurth, ca. 1350 -now dismantled-) and the Třeboň or Wittingau Altarpiece (convent of the Augustinians in Prague, of the so-called Master of Třeboň or Wittingau, c.1380-1390). In the same area, in the XV century, the so-called Master of the Garden of Paradise in Frankfurt or Master of the Upper Rhine stood out.

From the mid-15th century century, the evolution of art forms was marked by the development of Flemish and Italian painting in the new context of the Renaissance, but Gothic survived well into the 16th century.

- French Gothic altarpieces

- Třeboň or Wittingau altarpiece (ca. 1380)

Italian altarpiece from Gothic to Renaissance

Since the beginning of the XV century, a new aesthetic current that takes Greco-Roman Antiquity as its source of inspiration triumphs in Europe: the Renaissance. After initially prevailing on the Italian peninsula, the new artistic style spread rapidly, reaching its peak in the mid-XVI century. The Renaissance brought with it a revision of the Gothic forms, which will be replaced by elements of a classicist nature.

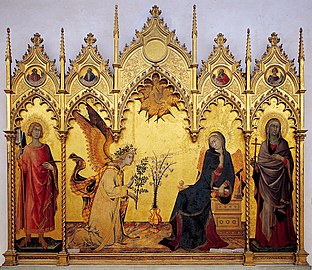

In Italy, the altarpiece (called there pala) had never acquired great proportions, since the tradition of fresco paintings in churches was maintained; although Giotto or Simone Martini, renowned fresco painters, also made outstanding polyptychs for altars. Almost all of Duccio's work is done in pale. Also noteworthy is L'altare di argento, the silver altarpiece from the Florence Baptistery (central compartments, by Betto di Geri and Leonardo di Giovanni, 1366 - the four lateral reliefs are by sculptors of the Quattrocento: Pollaiuolo, Verrocchio and two other goldsmiths-).

With the irruption of the new style, the architectural structure of the altarpiece becomes clearer and simpler (you can see how some altarpieces by Fra Angelico exemplify the evolution from one structure to another).

- Retablos de Fra Angelico

New techniques emerge, such as enameled terracotta (Della Robbia brothers), at the same time the use of marble, bronze or granite is generalized as opposed to polychrome wood. The typically Renaissance decorative elements, such as the grotesque, candelieri, the vegetable scrolls, the putti, the tondo or clypeus, or the flameros, come to decorate the new structures, formed by pilasters, columns or semi-columns, friezes and cornices, all clearly inspired by classical antiquity. Some altarpieces are integrated into the architectural space for which they have been designed, with trompe l'oeil effects. The pagan or profane influence ends up also transferring to religious images. All these elements will soon go beyond the Italian peninsula and will be exported to the rest of the European territories.

Flemish Late Gothic and Nordic Renaissance altarpieces

In the area ambiguously called Flanders by historiography, the Burgundian State was the protagonist of a cultural splendor that Johan Huizinga described as Autumn of the Middle Ages; and which continued into the Modern Age under the Habsburgs. Like the highly prized Flemish tapestries, Flemish altarpieces were exported throughout Europe, both pictorial polyptychs (the Van Eyck, Van der Weyden, Van der Goes) and sculptural ones, with a complex architectural composition and motifs derived from International Gothic. they received praiseworthy names (such as "the pearl of Brabant" or "the miracle of Dortmund").

In the kingdom of France, the work of sculptors such as Antoine Le Moiturier (altarpiece of the Last Judgment in the collegiate church of Saint-Pierre in Avignon, of which only two angels remain), and painters such as Jean Fouquet (the daring diptych for the funerary chapel of Agnès Sorel in the cathedral of Melun).

In the Central European cities of Germanic culture, around the Rhine and the Danube, which witnessed the birth of the printing press, with spectacular repercussions in the spread of humanism and the transformation of culture in the final decades of the century XV and early XVI century, highlighted the work of painters such as Pacher, Dürer, Grünewald, Altdorfer, Ratgeb, Baldung, the Cranach or the Holbein, who also developed in altarpieces. Alternatively, or integrated into the altarpieces themselves, the work of sculptors such as Veit Stoss, Nikolaus Gerhaert, Tilman Riemenschneider or Nicolas de Haguenau developed. The forms evolved from fixed panels of modest dimensions to large and complex articulated structures with complex architectural ornamentation. The wings were usually dedicated to pictorial representations of the saints, while the central panel was reserved for evangelical scenes in bulk carvings.

Starting in 1517, the impact of the Protestant Reformation was very notable, and as regards the altarpieces, it caused the destruction of many religious images; although there were also prominent Lutheran artists who continued to make altar pieces, such as the Cranachs.

The so-called "Altarpieces of Antwerp N#34;

In the 15th and XVI, the fame of the so-called "Antwerp altarpieces" spread throughout Europe. The commercial boom of the city of Antwerp had taken place especially after the decline of the city of Bruges, and it suffered a terrible blow with the Antwerp sack of 1576.

- Antwerp altarpieces

Spanish Renaissance altarpiece

It is common to establish a chronological periodization of the Renaissance in Spain between the High and the Low Spanish Renaissance, although the stylistic labels are of problematic use: "plateresque" applies to productions from the first third of the XVI century, characterized by the horror vacui, which They were compared to the work of silversmiths, and in which both the latest masters of the Gothic or Hispano-Flemish tradition fit as well as the introduction of new elements of Italian Renaissance origin; "mannerist" it is applied to the central third of the century (although it is an adjective that can be applied to the disciples of the great Italian figures of the beginning of the XVI as to the post-Tridentine period and up to the beginning of the XVII century); "Romanist" it is applied to the final third of the century, characterized by the sober forms of Gaspar Becerra and the great project of El Escorial.

Plateresque altarpiece

In Spain, the Renaissance aesthetic was slow to prevail, due to the roots of Gothic or Hispano-Flemish forms. At first, the Italianate forms appear timidly in the altarpieces (as they did in architecture), in the form of decorative details. Only late in the XVI century did a novel aesthetic take shape: the Plateresque style.

The Plateresque altarpiece combines Gothic elements with others of Italian roots, characterized by its narrative character (reliefs or paintings) and the development of the tabernacle that adopts a central and prominent position. Plateresque altarpieces are generally very flat, configured by means of pilasters or semi-columns, with the novelty of the baluster as a support. The decoration is usually stylized and minute, in the form of grotesques, scallops, heads of cherubs, putti, scrolls..., appearing new formal typologies, such as circular reliefs or those made in stiacciato.

In the Crown of Castile there are outstanding examples of Plateresque altarpieces:

- the main altarpiece of the Cathedral of Palencia, considered one of the first Renaissance altarpieces in Spain (contracted in 1504), work by Felipe Vigarny, Alejo de Vahía, Pedro de Guadalupe, Juan de Flandes and Juan de Valmaseda;

- the main altarpiece of the Royal Chapel of Granada, the work of Felipe Vigarny, decorated with scenes of the conquest of Granada and statues orantes of the Catholic Kings, by Diego de Siloé;

- the main altarpiece of the church of San Pelayo de Olivares de Duero (provincia de Valladolid);

- the main altarpiece of the Convent of St. Paul of Palencia;

- the altarpiece of the chapel of the Piety of the Church of San Miguel Archangel (Oñate);

- the altarpiece of the church of the Saviour (Calzadilla de los Barros), of Antón de Madrid (first third of the centuryXVI).

In the Crown of Aragon, simultaneously with the introduction of Italian Renaissance forms by Pedro Fernández de Murcia (altarpiece of Santa Elena in the cathedral of Gerona), the Gothic tradition of the alabaster altarpiece-exhibitor continued, adapting to the new aesthetics, highlighting in this area Damián Forment, to whom we owe:

- the main altarpiece of the Basilica of the Pilar of Zaragoza (1512-1518), in alabaster, of drip structure and almost round lump reliefs;

- the main altarpiece of the cathedral of Huesca (1520), made in alabaster, his body is a great three-scenes triptych showing the passion of Christ;

- the main altarpiece of the monastery of Poblet, of a more silvery character, with the flat veneration characteristics;

- the main altarpiece of the Cathedral of Santo Domingo de la Calzada, made of gold and polychrome wood, with lush decoration.

The work of Juan de Moreto, Juan de Salas and Gabriel Yoly was also notable in the Aragonese altarpieces of this period (altarpiece of the chapel of San Miguel of the cathedral of Jaca, main altarpiece of the cathedral of Teruel); continued in the central decades of the XVI century by Cosme Damián Bas (altarpieces from the Albarracín cathedral, some in wood without polychrome).

- Spanish silver altarpieces

Mannerist altarpiece

Starting in the 1530s, Mannerism, an evolution of 15th-century classicism, invaded all European artistic spheres. In Spain, the irruption of this style put an end to the last vestiges of the Gothic and imposed the validity of the Italianate style from that decade until practically the century XVII.

In the field of the altarpiece, the Mannerist style gave brilliant interpreters, with masterpieces that would be greatly admired and imitated. The first of them was Alonso Berruguete, one of the most renowned Spanish sculptors of all time. His most ambitious work, the main altarpiece of the Monastery of San Benito de Valladolid (1527-1532), can be found today in several parts, almost all of which are preserved in the National Museum of Sculpture in the same city. Berruguete's temperamental and unclassifiable art exhibits in this work some of the typical characteristics of Hispanic Mannerism, mixing typical elements of the most orthodox Renaissance (scallops, balusters, reliefs on tondo) with a peculiar dramatic sense that is completely anti-classical, in which forms are they submit to the general effect of expressiveness and movement. Manuel Álvarez, responsible in part for the great diffusion and success of the Berruguetesque style.

The other great Mannerist master, belonging like Berruguete to the Valladolid focus, was Juan de Juni. Like the first, he cultivates the Italianate style from a very personal point of view. Many of Juni's masterpieces were in the field of the altarpiece; he succeeded in conceiving his altarpiece creations as a unitary whole and not mere framework-architectures, and he did not hesitate to alter and deform the principles of classicism for the sake of expressiveness. The fact that the images and reliefs from June seem to overflow the frame that contains them is very striking, which gives these works great visual power and greater proximity to the viewer, prefiguring certain baroque tendencies. Some of his best-known altarpieces are the largest in the cathedral of Valladolid (commissioned to the artist for the church of Santa María la Antigua), the one in the Alderete chapel in San Antolín de Tordesillas and the one in the Benavente chapel in Santa Maria de Medina de Rioseco.

- Mannerist altarpieces

Romanist altarpiece

In the middle of the XVI century, the Council of Trent marks a caesura in religious experience and art in particular. The need for greater clarity and forcefulness in the transmission of the evangelical message causes certain mannerist formal excesses to be tempered. This is how the Roman style or Romanism emerged, which would be the predominant one until the end of the century, coexisting, however, with mannerism, which retained some validity. Following the new style, the altarpieces acquire a more architectural and monumental conception; The severity in the decoration is accentuated (pediments, free-standing columns, friezes, triglyphs and metopes), while the images become expressive and gesticulating, in an attempt to be persuasive.

The new current will be led by masters such as Gaspar Becerra, author of the main altarpiece of the cathedral of Astorga (1558-1562), a paradigmatic piece that will create a whole fashion, being widely copied. Other representative artists of this moment are Pedro López de Gámiz (main altarpiece of the convent of Santa Clara, Briviesca), Rodrigo de la Haya (who with his brother Martín made the main altarpiece of Burgos Cathedral) and Juan de Ancheta.

Perhaps the culminating moment of the Romanesque style, as well as its end, was the classicism that prevailed during the reign of Felipe II and the construction of the Monastery of El Escorial. The Escorial style marks the transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque in Spain. It is an art that dispenses with accessory elements, eliminating any decorative concession and giving prominence to the architectural support, which follows the classical canons almost obsessively, although introducing a gigantism rooted in Michelangelo. Regarding the altarpiece, the main example of this current was the main altarpiece of the Basilica of the monastery. Being a commission of great symbolic importance (since it had to preside over the space where the kings of Spain were buried) made this piece a unique work; The most expensive materials were used in its preparation (jaspers, polychrome marbles, fire-gilded bronze) as well as a host of artists among the most famous of their generation: Juan de Herrera gave the general layout, Pompeyo and Leone Leoni made the sculptures and It was even thought that a painting by Titian would preside over the set, although the pictorial part was finally commissioned to Pellegrino Tibaldi and Federico Zuccaro.

This monumental work can be considered the swan song of the Renaissance in Spain in the field of the altarpiece. The impact and novelty that it entailed prevailed well into the XVII century, collecting many examples that will be made from then on. of these innovations, such as the rigid superposition of orders, the use of stone instead of polychrome wood, the clear structuring and iconographic hierarchy, and above all, the emphasis that will be given from now on to the tabernacle or tabernacle, which, as happens in El Escorial, it often comes to be exempt and almost independent from the body of the altarpiece.

Other notable examples of an altarpiece from El Escorial are the largest in the collegiate church of San Luis de Villagarcía de Campos (Valladolid), designed by Juan de Herrera and carved by Juan Sáez de Torrecilla, or the one that presides over the Valladolid church of San Miguel and San Julián, the work of Adrián Álvarez.

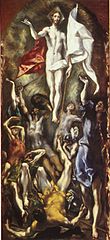

- Hypothetical reconstruction of the altarpiece of Doña María de Aragón, of El Greco (1596-1599)

Baroque altarpiece: 17th and 18th centuries

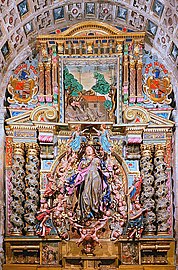

The Baroque was, perhaps, the golden age of the altarpiece, both for the large number of them that were made and for their artistic importance, their typological and formal variety, and their dimensions, which became completely monumental. At this time, moreover, with the implementation of the Counter-Reformation after the Council of Trent, the construction of altarpieces was consolidated in places where it had declined in previous centuries, such as areas of Germany, Austria, Poland, the Catholic Netherlands or Italy itself. In any case, the Iberian Peninsula continued to be the most creative and important center, with the novelty of exporting the churches and cathedrals that were being built at that time in the American colonies and elsewhere.

In the 17th and XVIII, the altarpiece took on an extraordinary role inside the churches, so that many times the architecture of the temples ends up being dependent on their placement, becoming general the flat headers with a blind front, or at most with windows open at the top so that they do not interfere with the structure of the altarpiece and adapt to it. At a time when art seeks closeness to the faithful, new typologies are generalized, such as the altarpiece with a dressing room (which had precedents in the Renaissance), the free-standing altarpiece as a ciborium or tabernacle, the transparent-altarpiece, with openings that allow light to pass through, the altarpiece-reliquary, which emerged from the resurgence of the cult of the relics of saints, etc.

Baroque altarpieces are usually conceived as an integral part of a larger decoration that extends throughout the church, and thus they sometimes match with frescoes painted on ceilings or walls, or with other altarpieces, repeating for example the so-called "collateral altarpieces" the shape and decoration of the main altarpiece or the main chapel. At this time the hierarchy of the decorative elements of the temple is strongly accentuated, while they tend to form a whole. Naturally, this is more palpable in the churches built ex-novo in the Baroque period, although old temples such as the cathedral of León suffered the influence of the new style at this time, designing decorations that were sometimes somewhat shocking with the preceding architecture.

Italian Baroque altarpieces

In the Italian Baroque, the iconography of the pale, following the theological recommendations of the Counter-Reformation, focuses on a single theme, such as the patron saint of the church or the corresponding altar, usually on canvases or in large sculptural groups.

- Italian Baroque altarpieces

Flemish Baroque altarpieces

In the Southern Netherlands, as a reaction to Protestant aniconism, the decoration of Catholic churches became extreme. Not only the altarpieces, but the pulpits and even the pillars of the naves became supports for sophisticated sculptural groups, while the large-scale creations of the Flemish school were added to the tradition of pictorial polyptychs, in much more simplified structures. of painting headed by Rubens.

- Flamenco Baroque altarpieces

- Rubens altarpieces at Antwerp Cathedral

French Baroque altarpieces

The relationship between French altarpieces and the complex baroque spirituality has been particularly studied.

- French Baroque altarpieces

Central European Baroque altarpieces

In Central Europe the Baroque was the art of the Counter-Reformation in the areas that were maintained or recovered by Catholicism (States of the Habsburgs of Vienna, South Germany, Poland); but also art in Lutheran areas. Late 17th century and early XVIII, the altarpieces merged with the architectural environment, which in turn blurred into sculptures and ornamental elements in all kinds of materials (stones, metals, and especially stucco).

- Central European Baroque altarpieces

Spanish Baroque altarpieces

Spanish Baroque altarpieces are very sophisticated, complex and varied in local schools. of the sacristy and the famous free-standing tabernacle, by Francisco Hurtado Izquierdo). In Salamanca at the end of the XVII century, the Churrigueresque style triumphed. In the Toledo of the first third of the XVIII century, Narciso Tomé achieved a highlight of the style (the famous «transparent»), which later neoclassical criticism denigrated as an example of baroque "bad taste". The granite filigrees on the Obradoiro façade of the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral (Fernando de Casas Novoa, also the author of traces of altarpieces, notably that of San Martín Pinario, along with Miguel de Romay) are often compared to the forms of these last baroque altarpieces. Throughout a century and a half, multifaceted artists (such as Alonso Cano) or specialized in one art (such as the architects Juan Gómez de Mora or José de Churriguera, the sculptors Alonso and Pedro de Mena, Gregorio Fernández, Martínez Montañés or Francisco Salzillo, or like the painters Murillo, Valdés Leal or Zurbarán) left a good part of their work in altarpieces of the time; while within baroque style altarpieces carvings or paintings from previous periods were also included (as occurs in the main altarpiece of the cathedral of Valencia).

A periodization in three phases has been proposed («extension of classicism» in the first third of the XVII century, « “castizo” or “genuinely Hispanic” altarpiece in the second half of the XVII century —phase subdivided into a first part, characterized by the Solomonic columns, and a second, due to the stipes—, and «Rococo altarpiece» in the first half of the XVIII century).

Portuguese Baroque altarpieces

The symbolism of the "eucharistic throne" in Portuguese baroque altarpieces has been investigated.

Colonial baroque altarpieces

The extraordinary decorative richness (both in the materials used and in the profusion of details) and some syncretic characteristics coming from the indigenous artistic substratum (although they basically respond to European aesthetic and religious criteria) characterize the baroque altarpieces of colonial cities of the Spanish and Portuguese empires (unified between 1580 and 1640). In addition to those of Spanish America and the Philippines, those of the Portuguese colonial cities of Goa (in India) and Salvador de Bahia (in Brazil) are particularly notable; those of the latter number in the hundreds (it was said that mass could be heard on a different day of the year -the same was said of the Mexican valley of Cholula-).

However, there was already production of altarpieces in Spanish America in the XVI century; both in the first ecclesiastical foundations of the Caribbean and in the continental territories. The one considered to be the oldest on the continent is that of San Juan Cuauhtinchán (Puebla), dateable to around 1527.

Contemporary age

At the middle of the XVIII century, the altarpiece was frequently invaded by Louis XV (Rococo) style decorations. The deep The criticism to which academicism submits the "excesses" it perceives in the Baroque, leads to the greater sobriety of Neoclassicism (even in transitional late-Baroque works, such as the chapel of El Pilar by Ventura Rodríguez and José Ramírez de Arellano), which at the beginning of the XIX century brings to the altarpieces the simplest forms of Greco-Roman doorways. Since the mid-19th century, eclectic and historicist altarpieces have been produced. Already in the XX century, the renewal of ecclesial aesthetics in Catholicism was radical, opening up to the artistic avant-gardes, especially from of the Second Vatican Council.

Contenido relacionado

Ababil

Patristics

Christ

![Ciborio de San Ambrosio de Milán (las columnas, del siglo IV, el dosel, posterior (entre el IX y el XII); el altar, firmado por Vuolvino, entre el año 824 y el 860.[23]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e5/9663_-_Milano_-_S._Ambrogio_-_Ciborio_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto_25-Apr-2007.jpg/179px-9663_-_Milano_-_S._Ambrogio_-_Ciborio_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto_25-Apr-2007.jpg)

![Frontal de altar de la ermita de San Quirce de Durro[26]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bd/MNAC.Barcelona_-_Rom%C3%A0nic_Fontal_de_Durro.jpg/355px-MNAC.Barcelona_-_Rom%C3%A0nic_Fontal_de_Durro.jpg)

![Detalle del retablo de Westminster (ca. 1270).[34]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f7/Westminster_Retable.jpg)

![El retablo de Santa María de Mave (arriba -abajo, el frente de altar-), actualmente conservado en la capilla de San Nicolás de la catedral de Burgos. Su datación es muy imprecisa (siglos XIII-XIV).[35]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/82/Burgos_-_Catedral_049_-_Capilla_de_San_Nicolas.jpg/215px-Burgos_-_Catedral_049_-_Capilla_de_San_Nicolas.jpg)

![Virgen con el Niño, inicialmente parte del mismo retablo, que permanece en la iglesia del monasterio de Santa María de Mave.[36]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ce/Mave_-_Monasterio_de_Santa_Maria_la_Real_05.jpg/186px-Mave_-_Monasterio_de_Santa_Maria_la_Real_05.jpg)

![Retablo de los santos Miguel e Hipólito en Palau-del-Vidre, de Arnaud Gassies (1454), conocido como «retablo de los vidrieros» (artesanado que da nombre a esa localidad).[58]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Palau_Saint-Michel_Saint-Hippolite_%281454%29.jpg/154px-Palau_Saint-Michel_Saint-Hippolite_%281454%29.jpg)

!['Retablo de la vida de la Virgen y de san Francisco, de Nicolás Francés (1445-1460).[59]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ee/Nicolas_frances-prado.jpg/176px-Nicolas_frances-prado.jpg)

![San Antonio y San Cristóbal, detalle del retablo mayor de la iglesia de San Benito de Calatrava (Sevilla), del taller de Juan Sánchez de Castro (ca. 1470).[60]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ce/San_Antonio_Abad_y_San_Cristobal.jpg/125px-San_Antonio_Abad_y_San_Cristobal.jpg)

![Retablo mayor de la catedral de Tudela, de Pedro Díaz de Oviedo y Diego del Águila.[61]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/Catedral_de_Tudela._Retablo_mayor..TIF/lossless-page1-202px-Catedral_de_Tudela._Retablo_mayor..TIF.png)

![Retablo de la Virgen del Santísimo Sacramento en Saint-Georges de Haguenau.[72]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7b/Haguenau_StGeorges32.JPG/269px-Haguenau_StGeorges32.JPG)

![Capilla de Nuestra Señora de Saint-Sulpice de Fougères.[73]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/Bretagne_Ille_Fougeres5_tango7174.jpg/135px-Bretagne_Ille_Fougeres5_tango7174.jpg)

![Capilla de la Natividad de Saint-Vulfran de Abbeville.[74]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/55/Abbeville%2C_Coll%C3%A9giale_Saint-Vulfran_%286%29.jpg/135px-Abbeville%2C_Coll%C3%A9giale_Saint-Vulfran_%286%29.jpg)

![Retablo Grabow, del Maestro Bertram (1379).[75]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c9/Meister_Bertram_von_Minden_-_Grabow_Altarpiece_-_WGA14309.jpg/707px-Meister_Bertram_von_Minden_-_Grabow_Altarpiece_-_WGA14309.jpg)

![Retablo de la Crucifixión, de Jacques de Baerze[76] (1390), encargado por Felipe el Atrevido para la cartuja de Champmol.[77]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6c/Dijon_Salle_des_Gardes_Retable_Crucifixion1.jpg/320px-Dijon_Salle_des_Gardes_Retable_Crucifixion1.jpg)

![Retablo con escenas de la pasión en Saint-Clair-Saint-Léger de Souppes-sur-Loing.[78]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/71/Souppes_Saint-Clair-Saint-L%C3%A9ger_Retabel_691.JPG/270px-Souppes_Saint-Clair-Saint-L%C3%A9ger_Retabel_691.JPG)

![Tríptico escultórico (abierto) en la iglesia de Sogn Gieri (Suiza, siglo XIV).[79]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7f/Sogn_Gieri_Altar.jpg/485px-Sogn_Gieri_Altar.jpg)

![Retablo de la Walpurgiskirche[80] de Alsfeld.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/Walpurgiskirche_Alsfeld_Altar_276.JPG/405px-Walpurgiskirche_Alsfeld_Altar_276.JPG)

![Retablo de la Marienkirche de Gelnhausen.[81]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/68/Gelnhausen_-_Marienkirche_-_Laienaltar_-_5492-94.jpg/406px-Gelnhausen_-_Marienkirche_-_Laienaltar_-_5492-94.jpg)

![El llamado "altar Tucher", del llamado Maestro del altar Tucher[82] (Núremberg, ca. 1440-1450).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8b/Meister_des_Tucher-Altars_001.jpg/379px-Meister_des_Tucher-Altars_001.jpg)

![Retablo de los Reyes Magos (Dreikönigsaltar)[83] en la catedral de Colonia, de Stefan Lochner (1445).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/Dombild_K%C3%B6ln1.JPG/348px-Dombild_K%C3%B6ln1.JPG)

![El llamado "tríptico" o "políptico Stefaneschi",[88] de Giotto, ca. 1320 (vista anterior -recto-).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7c/Polittico_stefaneschi%2C_retro.jpg/303px-Polittico_stefaneschi%2C_retro.jpg)

![El llamado "políptico de Santa Catalina de Alejandría",[89] de Simone Martini, 1320.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cd/Simone_Martini_012.jpg/383px-Simone_Martini_012.jpg)

![Tríptico de la Virgen con el Niño y los santos Pedro y Pablo,[90] proveniente de la Pieve[91] de San Giovanni d'Asso, de Ugolino di Nerio (1320-1325).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/Ugolino_di_nerio%2C_Trittico_della_Madonna_col_Bambino_e_i_santi_Pietro_e_Paolo.jpg/283px-Ugolino_di_nerio%2C_Trittico_della_Madonna_col_Bambino_e_i_santi_Pietro_e_Paolo.jpg)

![Reconstrucción de la Pala della beata Umiltà ("retablo de la beata Humildad"),[92] de Pietro Lorenzetti, ca. 1341.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/Pietro_lorenzetti%2C_pala_della_beata_umilt%C3%A0.jpg/272px-Pietro_lorenzetti%2C_pala_della_beata_umilt%C3%A0.jpg)

![Pala della Crocifissione[93] ("retablo de la Crucifixión"), de Jacopo di Cione,[94] Nardo di Cione[95] y su taller (ca. 1368).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Cione%2C_Jacopo_di_-_Crucifixion_-_National_Gallery.jpg/242px-Cione%2C_Jacopo_di_-_Crucifixion_-_National_Gallery.jpg)

![El llamado "tríptico de San Pedro Mártir"[96] (1428-1429)](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Angelico%2C_pala_di_san_pier_maggiore%2C_1425_ca..jpg/202px-Angelico%2C_pala_di_san_pier_maggiore%2C_1425_ca..jpg)

![Anunciación, pintada como pala d'altare para el convento de Santo Domingo de Fiesole[97] (1430-1435).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Angelico%2C_prado.jpg/189px-Angelico%2C_prado.jpg)

![El llamado tabernacolo dei Linaioli[98] (1432-1433).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Angelico%2C_linaioli_tabernacle_02.jpg/95px-Angelico%2C_linaioli_tabernacle_02.jpg)

![El llamado "tríptico de Cortona",[99] (1436-1437).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3e/Angelico%2C_cortona_poliptych_01.jpg/206px-Angelico%2C_cortona_poliptych_01.jpg)

![La llamada pala di Perugia,[100] (1438).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/Fra_Angelico_-_Perugia_Altarpiece_%28in_modern_frame%29_-_WGA00496.jpg/217px-Fra_Angelico_-_Perugia_Altarpiece_%28in_modern_frame%29_-_WGA00496.jpg)

![Reconstrucción de la llamada pala di San Marco,[101] (1440).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/TotalPalaSanMarco.jpg/206px-TotalPalaSanMarco.jpg)

![La llamada pala di Bosco ai Frati,[102] (1450-1452).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/Angelico%2C_Bosco_ai_Frati_Altarpiece.jpg/141px-Angelico%2C_Bosco_ai_Frati_Altarpiece.jpg)

![La llamada pala di Pesaro,[106] de Giovanni Bellini (1471-1483).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/80/Pala_di_pesaro_01.jpg/184px-Pala_di_pesaro_01.jpg)

![Montaje actual del llamado "políptico de San Pedro",[107] de Perugino, ca. 1496. La disposición original era más compleja.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/97/AscensionPeruginMBALyon.jpg/175px-AscensionPeruginMBALyon.jpg)

![Reconstrucción del llamado "políptico Recanati",[108] de Lorenzo Lotto, ca. 1506](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/Lotto%2C_polittico_di_recanati.jpg/224px-Lotto%2C_polittico_di_recanati.jpg)

![El llamado "políptico de Arcevia",[109] de Luca Signorelli (1507).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/09/Luca_signorelli%2C_polittico_di_arcevia.jpg/221px-Luca_signorelli%2C_polittico_di_arcevia.jpg)

![Retablo de la iglesia de Santa Corona[110] (Vicenza), de Bartolomeo Montagna.[111]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0c/Vicenza%2C_santa_corona%2C_altare_porto-pagello_di_bartolomeo_montagna_02.JPG/202px-Vicenza%2C_santa_corona%2C_altare_porto-pagello_di_bartolomeo_montagna_02.JPG)

![El retablo llamado "la perla de Brabante", ca. 1470.[123]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bb/Dieric_Bouts_003.jpg/544px-Dieric_Bouts_003.jpg)

![El llamado Pacher-Altar,[124] retablo de St. Wolfgang im Salzkammergut de Michael Pacher(1471).[125]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3f/Alois_H%C3%A4nisch_Pacher-Altar_St_Wolfgang.jpg/192px-Alois_H%C3%A4nisch_Pacher-Altar_St_Wolfgang.jpg)

![El llamado "retablo" o "altar de la Dormición" o de Cracovia,[126] de Veit Stoss (1477-1489).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6a/Altar_of_Veit_Stoss%2C_St._Mary%27s_Church%2C_Krakow%2C_Poland.jpg/259px-Altar_of_Veit_Stoss%2C_St._Mary%27s_Church%2C_Krakow%2C_Poland.jpg)

![El llamado "retablo" o "altar Kefermarkter" (1490-1497).[127]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/Altar_1.JPG/200px-Altar_1.JPG)

![El llamado "retablo" o "altar de la Sagrada Sangre" (Heiligblutaltar),[128] de Tilman Riemenschneider (1501—1505). Del mismo autor, o de su círculo, son el retablo de la iglesia de San Pedro y San Pablo de Detwang,[129] el Zwölfbotenaltar[130] y el Marienretabel de la Herrgottskirche[131] de Creglingen.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a4/Tilman_Riemenschneider_Heilig_Blut_Altar_1.jpg/180px-Tilman_Riemenschneider_Heilig_Blut_Altar_1.jpg)

![Parte de los paneles del llamado retablo o "altar de San Sebastián" (Sebastianaltar)[132] del monasterio de San Florián[133] (Sankt Florian, Austria), de Altdorfer (1509-1519).[134]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c6/Albrecht_Altdorfer_028.png/215px-Albrecht_Altdorfer_028.png)

![El llamado "retablo" o "altar Herrenberger",[135] de Jerg Ratgeb (1518-1521).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/be/Herrenberger_Altar_BMK.jpg/175px-Herrenberger_Altar_BMK.jpg)

![El llamado "retablo" o "altar Schneeberger" (Wolfgangskirche, Schneeberg),[136] de Lucas Cranach el Viejo, 1532–1539 (vista anterior -recto-).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1f/Schneeberg_St._Wolfgangskirche_altar_piece_front_%28aka%29.jpg/335px-Schneeberg_St._Wolfgangskirche_altar_piece_front_%28aka%29.jpg)

![Retablo de San Juan Bautista de la iglesia del Salvador de Valladolid, ca. 1500 (el banco se realizó por artistas locales).[137]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/Valladolid_iglesia_Salvador_retablo_San_Juan-Bautista_ni.jpg/240px-Valladolid_iglesia_Salvador_retablo_San_Juan-Bautista_ni.jpg)

![Retablo de la Marienkirche de Lübeck, del llamado Maestro de 1518[138]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/Marienkirche_Luebeck_altar.jpg/254px-Marienkirche_Luebeck_altar.jpg)

![Retablo de la Marienkirche de Waase.[139]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8f/Waase_St._Marien_Altar_Gesamtansicht.jpg/241px-Waase_St._Marien_Altar_Gesamtansicht.jpg)

![Retablo de San Lamberto de Affeln[140] (1525).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6f/Flandrischer_Altar_in_der_St.-Lambertuskirche_zu_Affeln_%28Stadt_Neuenrade%29%2C_Sauerland%2C_NRW.jpg/208px-Flandrischer_Altar_in_der_St.-Lambertuskirche_zu_Affeln_%28Stadt_Neuenrade%29%2C_Sauerland%2C_NRW.jpg)

![Retablo de la Virgen de los mareantes en la capilla del Cuarto del Almirante de los Real Alcázar de Sevilla, de Alejo Fernández (1531-1536). El edificio tiene otras capillas con notables retablos.[148]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6f/Virgen_de_los_mareantes_Alcazar_sevilla_002.jpg/181px-Virgen_de_los_mareantes_Alcazar_sevilla_002.jpg)

![Imagen de San Benito de Nursia, talla de la hornacina central del antiguo retablo de San Benito el Real de Valladolid, de Alonso Berruguete (hoy desmontado y exhibido por piezas en el Museo Nacional de Escultura).[151]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cc/Alonso_Berruguete%2C_San_Benito_de_Nursia.jpg/135px-Alonso_Berruguete%2C_San_Benito_de_Nursia.jpg)

![Retablo mayor de Santa María Coronada (Medina Sidonia), de Roque Balduque.[152]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/IglesiaSantaMaria-Retablo.JPG/240px-IglesiaSantaMaria-Retablo.JPG)

![Retablo mayor de la iglesia de Santa Ana (Sevilla), del pintor Pedro de Campaña y el escultor Pedro Delgado (1557).[153]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/04/Main_altar_-_Iglesia_de_Santa_Ana_-_Seville_%282%29.JPG/120px-Main_altar_-_Iglesia_de_Santa_Ana_-_Seville_%282%29.JPG)

![Retablo del Hospital de Santa Cruz (Toledo), hoy en San Juan de los Reyes, de Felipe Bigarny y Francisco de Comontes (1541-1552).[154]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/86/Toledo_-_M%C2%BA_de_San_Juan_de_los_Reyes_05.jpg/215px-Toledo_-_M%C2%BA_de_San_Juan_de_los_Reyes_05.jpg)

![Retablo mayor de la iglesia de San Pedro de Zumaya, de Juan de Ancheta. En la misma iglesia hay otros notables retablos.[160]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Zumaia_-_Iglesia_de_San_Pedro_08.JPG/202px-Zumaia_-_Iglesia_de_San_Pedro_08.JPG)

![Retablo de las Ánimas del Juicio Final, de Nicolás Borrás (1574).[161]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b5/Borras-retablo-de-animas.jpg/172px-Borras-retablo-de-animas.jpg)

![Pala de la cappella Panciatichi de la catedral de Florencia, pintada por Domenico Pugliani.[163]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/48/Cappella_panciatichi%2C_01_pala_di_domenico_pugliani.JPG/135px-Cappella_panciatichi%2C_01_pala_di_domenico_pugliani.JPG)

![Retablo de traza barroca de la capilla de la Madonna de Brujas (que exhibe en su centro una talla de Miguel Ángel de comienzos del siglo XVI) en la iglesia de Nuestra Señora de Brujas.[164]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/10/Michelangelo%27s_Madonna_and_Child_in_Brugge.jpg/277px-Michelangelo%27s_Madonna_and_Child_in_Brugge.jpg)

![Retablo de la Asunción de la Virgen en la iglesia de San Nicolás de los Campos de París,[167] de Simon Vouet y Jacques Sarrazin (1629).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/%C3%89glise_Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs_%C3%A0_Paris_2.jpg/135px-%C3%89glise_Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs_%C3%A0_Paris_2.jpg)

![Retablo mayor de la iglesia de Saint-Jean-du-Marché de Troyes,[168] de traza de François Girardon y pintura de Pierre Mignard (Bautismo de Cristo).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e8/Troyes_%2810%29_%C3%89glise_Saint-Jean_07.JPG/135px-Troyes_%2810%29_%C3%89glise_Saint-Jean_07.JPG)

![Retablo mayor de la catedral de Cavaillon,[169] de Pierre Mignard.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a0/Cavaillon-cath%C3%A9drale.jpg/115px-Cavaillon-cath%C3%A9drale.jpg)

![Retablo de la cartuja de Vauclair.[170]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/19/Gilt_and_Polychrome_Wood_Altarpiece%2C_Siorac-de-Rib%C3%A9rac%2C_Dordogne%2C_France.jpg/240px-Gilt_and_Polychrome_Wood_Altarpiece%2C_Siorac-de-Rib%C3%A9rac%2C_Dordogne%2C_France.jpg)

![Altar mayor de la Michaelerkirche de Viena.[171]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fb/Wien_Michaelerkirche_Hochaltar_1.jpg/135px-Wien_Michaelerkirche_Hochaltar_1.jpg)

![Retablos de la Wallfahrtskirche de Maria Plain[172] en Salzburgo.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9e/Maria_Plain_Altar.jpg/240px-Maria_Plain_Altar.jpg)

![Retablo mayor de la iglesia de San Nicolás de Malá Strana[173] en Praga.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fd/Chram_sv_Mikulase_interier_oltar.jpg/135px-Chram_sv_Mikulase_interier_oltar.jpg)

![Retablos de la iglesia de San Nicolás (Bernbeuren).[174]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e5/Bernbeuren_Pfarrkirche_2.jpg/240px-Bernbeuren_Pfarrkirche_2.jpg)

![Retablo de la iglesia de San Cosme y San Damián en Stade, de Christian Precht[175] (1677), una iglesia luterana.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/42/Stade-StCosmae_01_Ausschnitt.jpg/128px-Stade-StCosmae_01_Ausschnitt.jpg)

![Altar de la Schloßkirche de Weesenstein,[176] una iglesia luterana.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/46/Weesenstein-Altar_LC0033.jpg/117px-Weesenstein-Altar_LC0033.jpg)

![Retablo mayor de la Gertrudenkirche de Osnabrück, de Thomas Simon Jöllemann[177] (1717-1729).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/63/Osnabr%C3%BCck_Gertrudenkirche_Hochaltar_oben.jpg/215px-Osnabr%C3%BCck_Gertrudenkirche_Hochaltar_oben.jpg)

![Retablo mayor de la Asamkirche[178] de Múnich, de los hermanos Asam (1733-1746).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/Asamkirche_%28HDR%29_%288419358438%29.jpg/120px-Asamkirche_%28HDR%29_%288419358438%29.jpg)

![Tablas del "retablo Portaceli",[183] de Ribalta.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2d/Museu_de_Belles_Arts_de_Val%C3%A8ncia%2C_sala_dels_Ribalta.JPG/360px-Museu_de_Belles_Arts_de_Val%C3%A8ncia%2C_sala_dels_Ribalta.JPG)

![Retablo mayor de la iglesia del convento de las Descalzas Reales (Valladolid), de Juan de Muniátegui,[184] Gregorio Fernández y Santiago Morán, 1612.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/37/Valladolid_-_M%C2%BA_Descalzas_Reales_4.jpg/202px-Valladolid_-_M%C2%BA_Descalzas_Reales_4.jpg)

![Retablo mayor de la iglesia del monasterio de las Huelgas Reales (Valladolid), de Francisco de Praves, Gregorio Fernández y Tomás de Prado,[185] 1613.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Retablo-Huelgas-Reales-Valladolid.jpg/196px-Retablo-Huelgas-Reales-Valladolid.jpg)

![Monasterio de San Salvador (Celanova), de Francisco de Castro Canseco.[187]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e8/Celanova_-_Monasterio_de_San_Salvador_06.JPG/180px-Celanova_-_Monasterio_de_San_Salvador_06.JPG)

![Retablo de la capilla de Nossa Senhora da Doutrina en la iglesia de San Roque (Lisboa).[191] El mismo templo contiene otros notables retablos, y el museo del que forma parte, una excepcional colección de arte sacro, incluyendo retablos de otras procedencias.[192]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8f/Capela_de_Nossa_Senhora_da_Doutrina_-_Igreja_de_S%C3%A3o_Roque_-_Lisbon_%282%29.JPG/405px-Capela_de_Nossa_Senhora_da_Doutrina_-_Igreja_de_S%C3%A3o_Roque_-_Lisbon_%282%29.JPG)

![Retablo mayor y laterales de la iglesia del convento de Santa Clara-a-Nova.[193]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e0/IsabPorCoimbraClaranova.jpg/179px-IsabPorCoimbraClaranova.jpg)

![Retablo mayor de la catedral Basílica de San Salvador (Salvador de Bahía, Brasil), antigua iglesia de los jesuitas, de João Correia (1665-1670).[198]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5f/Salvador-JesuitChurch1.jpg/405px-Salvador-JesuitChurch1.jpg)

![Retablo mayor y laterales de la iglesia del convento de San Francisco (Salvador de Bahía).[199]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2a/StFranciscoChurch2-CCBY.jpg/360px-StFranciscoChurch2-CCBY.jpg)

![Tras el altar mayor de la iglesia de la Magdalena se dispone a modo de retablo[203] un grupo escultórico de Carlo Marochetti.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e4/%D0%90%D0%BB%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%8C_%D1%86%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%BA%D0%B2%D0%B8_%D0%9C%D0%B0%D0%B4%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD.%D0%9F%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%B6.jpg/291px-%D0%90%D0%BB%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%8C_%D1%86%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%BA%D0%B2%D0%B8_%D0%9C%D0%B0%D0%B4%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD.%D0%9F%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%B6.jpg)

![Tras el altar mayor de la basílica del Sacré Cœur se dispone un retablo neorrománico.[204]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9c/Sacre_Coeur_-_Choeur%2C_Abside_et_Mosaique.jpg/179px-Sacre_Coeur_-_Choeur%2C_Abside_et_Mosaique.jpg)

![El altar de la iglesia de San Engelberto (Colonia)[205] muestra la simplicidad decorativa de las iglesias del siglo XX.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/St._Engelbert_K%C3%B6ln_Innenraum.jpg/270px-St._Engelbert_K%C3%B6ln_Innenraum.jpg)

![Retablo de Torreciudad, de Joan Mayné.[206]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Santuario_de_Torreciudad._Iglesia.jpg/478px-Santuario_de_Torreciudad._Iglesia.jpg)