Altamira cave

The Altamira cave is a natural cavity in the rock where one of the most important pictorial and artistic cycles of prehistory is preserved. It is part of the Altamira cave and rock art group Paleolithic of the Cantabrian coast, declared a World Heritage Site by Unesco. It is located in the Spanish municipality of Santillana del Mar, in Cantabria, about two kilometers from the urban center, in a meadow from which it took its name.

Since its discovery, in 1868, by Modesto Cubillas and its subsequent study by Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, it has been excavated and studied by the main prehistorians of each era once its attribution to the Paleolithic was admitted.

The paintings and engravings in the cave belong mainly to the Magdalenian and Solutrean periods and, some others, to the Gravettian and early Aurignacian, the latter according to tests using uranium series. In this way, it can be ensured that the cave was used during various periods, totaling 22,000 years of occupation, from about 36,500 to 13,000 years ago, when the main entrance to the cave was sealed by a landslide, all within the Paleolithic. top.

The style of a large part of his works falls within the so-called «Franco-Cantabrian school», characterized by the realism of the figures represented. It contains polychrome paintings, engravings, black, red and ocher paintings that represent animals, anthropomorphic figures, abstract and non-figurative drawings.

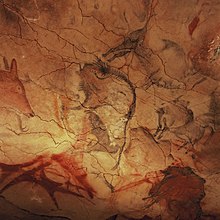

As for its polychrome ceiling, it has received qualifications such as the "Sistine Chapel" of rock art; "...the most extraordinary manifestation of this Paleolithic art...", "...the first decorated cave that was discovered and that continues to be the most splendid" and "...if [Paleolithic] cave painting is an example of great artistic ability, the Altamira cave represents its most outstanding work" indicate the great quality and beauty of the work of the Magdalenian man in this enclosure.

It was declared a World Heritage Site by Unesco in 1985. In 2008, the nomination was extended to 17 other caves in the Basque Country, Asturias and Cantabria itself, renaming the complex "Cueva de Altamira" and Paleolithic rock art from northern Spain".

History of discovery and recognition

The Altamira cave was discovered in 1868 by an Asturian weaver named Modesto Cubillas (Modesto Cobielles Pérez) who, while hunting, found the entrance while trying to free his dog, which was trapped between the cracks in some rocks for chasing a dam. At that time, the news of the discovery of a cave did not have the slightest significance among the neighborhood in the area, since it is a karstic terrain, characterized by already having thousands of caves, so the discovery of one more it was nothing new.

Cubillas told Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, a wealthy local owner and "mere fan" of paleontology, whose farm he was a sharecropper; however, he did not visit it until at least 1875, and most likely in 1876. He toured it in its entirety and recognized some abstract signs, such as repeated black stripes, to which he did not attach any importance because he did not consider them the work of man. Three or four years later, in the summer of 1879, Sautuola returned to Altamira for the second time, this time accompanied by his five-year-old daughter María Sanz de Sautuola y Escalante. He was interested in excavating the entrance to the cave. with the aim of finding some remains of bones and flint, like the objects he had seen at the World's Fair in Paris in 1878.

The discovery of the cave paintings was actually made by the girl. While her father remained at the mouth of the cave, she went inside until she reached a side room. There she saw some paintings on the ceiling and ran to tell her father. Sautuola was surprised to see the magnificent set of paintings of those strange animals that covered almost the entire vault.

The following year, 1880, Sautuola published a brief booklet entitled Brief notes on some prehistoric objects from the province of Santander. In it he supported the prehistoric origin of the paintings and included a graphic reproduction. He presented his thesis to the professor of Geology at the University of Madrid, Juan Vilanova, who adopted it as his own. Despite everything, Sautuola's opinion was not accepted by the French Cartailhac, Mortillet and Harlé, the most expert scientists in prehistoric and paleontological studies in Europe.

The Altamira paintings were the first large-scale prehistoric pictorial group known at the time, but such discovery determined that the study of the cave and its recognition raised a whole controversy regarding the accepted approaches in the prehistoric science of the moment. The novelty of the discovery was so surprising that it provoked the logical mistrust of scholars. It was even suggested that Sautuola himself must have painted them between the two visits he made to the cave, thus denying their Paleolithic origin, or even attributing the work to a French painter who had been staying at the cave guide's house, although most French experts considered Sautuola to be one of the dupes. The realism of his scenes sparked, at first, a debate about their authenticity. Evolutionism, applied to human culture, led to the deduction that ancient and savage tribes should not have art and that from then until now there would have been a continuum of progress. Logically if art is a symbol of civilization it should have appeared in the last human stages and not in savage peoples of the Stone Age. Its recognition as an artistic work carried out by men of the Paleolithic era was a long process in which studies on prehistory were also defined.

Neither Vilanova's ardent defense at the International Congress of Anthropology and Archeology, held in Lisbon in 1880, nor Sautuola's eagerness prevented Altamira's disqualification. But a renowned Sevillian liberal humanist and politician, Miguel Rodríguez Ferrer, published an article in the prestigious magazine La Ilustración Española y Americana (1880), endorsing the authenticity of the paintings and highlighting their immense value. Giner de los Ríos, as director of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza, commissioned a study to the geographer Rafael Torres Campos and the geologist Francisco Quiroga, who issued an unfavorable report, which they published in the institution's bulletin.

Opposition became more and more widespread. In Spain, at the session of the Spanish Society of Natural History on December 1, 1886, the director of the National Chalcography ruled that:

(...) such paintings have no characters of the art of the Stone Age, no archaic, no Assyrian, no Phoenician, and only the expression that would give a medium disciple of the modern school (...).Eugenio Lemus and Olmo

Sautuola and his few followers fought against that sentence. The death of Sautuola in 1888 and that of Vilanova in 1893, plunged into discredit for their defense, seemed to definitively condemn Altamira's paintings to be a modern fraud.

However, its value was confirmed by the frequent finds of other similar pieces of furniture art in numerous European caves. At the end of the 19th century, mainly in France, cave paintings undeniably associated with the figurines, reliefs and engraved bones found in Paleolithic archaeological levels, together with the remains of animals that have disappeared from the peninsular fauna or are extinct, such as mammoth, reindeer, bison and others. In this recognition, Henri Breuil highlighted his works on the theme "parietal art", very positively. Presented at the congress of the French Association for the Advancement of Sciences in 1902, they caused substantial changes in the mentality of the researchers of the time.

Émile Cartailhac had been one of the biggest opponents of the authenticity of Altamira, but the discovery of engravings and paintings from 1895 in the French caves of La Mouthe, Combarelles and Font-de-Gaume, made him reconsider. his position. After visiting the cave, he wrote in the magazine L'Anthropologie (1902) an article entitled La grotte d' Altamira. Mea culpa d'un sceptique (The cave of Altamira. Mea culpa de un sceptique). This article led to universal recognition of the Paleolithic nature of the Altamira paintings.

Once the authenticity of the paintings was established, the debate about the work itself began. The divergence between the researchers centered around the chronological precision, the mysterious purpose of the same and its artistic and archaeological values. These issues affected not only the Altamira cave, but all the Quaternary rock art discovered.

Physical description of the cave

Located on the side of a small calcareous hill of Pliocene origin, with the entrance at 156 m s. no. m. and at an elevation of about 120 meters above the Saja River, which passes about two kilometers away. km, since the Bay of Biscay had a lower level. This situation must have been privileged for hunters since it allowed them to dominate an extensive terrain and have refuge simultaneously.

About 13,000 years ago, in the late Magdalenian, the cave entrance collapsed, sealing the entrance, allowing the preservation of its paintings and engravings, and of the archaeological site itself.

Altamira cave is relatively small, only 270 meters long. It presents a simple structure formed by a gallery with few ramifications and ends in a long, narrow gallery that is difficult to navigate.

The temperature and humidity of the air in the Great Hall of the cave remain more or less constant throughout the year, as Breuil and Obermaier were able to verify with their measurements with value ranges of 13.5-14, 5°C and 94-97% respectively.

The study of the composition of the rock was carried out thanks to the fact that the Spanish authorities provided a piece of the ceiling of the cave in the 1960s to Dr. Pietsch for analysis and in this way he was able to reproduce it for the replicas that would later be housed in the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid and in the Deutsches Museum in Munich. The analysis indicated:

It is a consistent compact and finely crystallized limestone, of uniform yellow colour; some irregular areas of intense yellow color that look like stains are composed of calcite that contains siderite. In addition, other areas appear...Pietsch, 1964, pp. 61-62

Other details were also offered, and it was concluded that the limestone was almost pure, with a minimal dolomitic component —with a proportion of Mg no greater than 1.3%—

Seeing its current plan, it is difficult to understand how the living area and the room of the polychromes were used, so it must be imagined as an almost continuum in the period of the paintings. In the excavations, at least, five important collapses of the cave: one pre-Solutrean, prior to the Solutrean occupation, when the next one occurred, prior to one that coincides with the Magdalenian site, and two more that left blocks on the stalagmitic layer, which had been found on said site, and that they were, most likely, before the end of the Pleistocene (about 12,000 years ago). Minor cave-ins have continued, one nearly injuring Obermaier during his excavations in the 1920s.

Several areas are currently defined, which, although not all of them have their own agreed names, are usually mentioned as: lobby, «Great room of the polychromes», great room of the tectiformes, gallery, room of the black bison, «Room of the hole" (room prior to the horse's tail), and the "Cola de caballo". Or, on other occasions, by means of a numbering based on a plan, especially the one made by Obermaier and Breuil.

Lobby

It is a large hallway, illuminated by natural light before the cave entrance collapsed. It was especially part of the place inhabited for generations since the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic, or at least they are the remains that remain of the shelter that, more probably, was the habitual place of residence of the inhabitants of the cave. Pieces have been found in it of interest that have helped to date and to understand the way of life.

The main archaeological excavations carried out throughout history have been in this room, as indicated below.

Great Room

"Great room", "Great hall", "Great room of polychromes", "Hall of animals", "Great Ceiling", "Hall of frescoes" and many other names are those that it has received the second room and is the one that houses the large group of polychrome paintings, nicknamed by Déchelette the "Sistine Chapel of Quaternary Art". Its vault continues to maintain its 18 m length by 9 m width, but its original height (between 190 and 110 cm) has been increased by lowering the floor to facilitate the comfortable contemplation of the paintings, although a central witness of the original height has been maintained.

In prehistoric times it must have received some natural lighting from the opening through the vestibule, although it would be insufficient to carry out the polychrome and ensemble work.

Other rooms

In the other rooms and corridors, in which there are also less important artistic manifestations, they are out of reach of sunlight, so all activity was carried out with artificial lighting, although no remains of habitual occupation have been found., only sporadic access.

Dating and periodization

In general, the art of the Franco-Cantabrian region is framed within the Upper Paleolithic, although we must differentiate between the Iberian Upper Paleolithic and the Cantabrian Upper Paleolithic as indicated, for example, by Fullola Pericot quoting Barandiarán Maestu.

There is no agreement on the dating of the different archaeological pieces found nor on the dating of the paintings, as shown below, where there are results from different methods and scholars. In the list of dates that are offered in the specialized literature, not only must the different values be taken into account, but also the different measured variables: the dates of the general and local artistic periods, the dates of occupation of the caves, the dates of realization of the paintings according to the different methods, the dating of archaeological pieces, etc.

Another factor that could have led to confusion has been that a large number of scholars have considered that the paintings, not absolutely datable to the end of the century, XX and more precisely in the XXI, should be assigned to the occupation periods found and that these have been classically considered only Solutrean and Magdalenian. However, when the red paintings they have been studied from the stylistic point of view, they have been included in the Gravettian, delaying the first occupation date by some 4000 years, in fact in the archaeological studies carried out in the first decade of the 21st century this trend was confirmed by finding a level of Gravettian occupation.

In 2012 a study was published dating several paintings in some northern caves, including one of the clavate signs in the Great Room, which delayed the first works to the Aurignacian, in the case of Altamira to 35,600 before present, just at the beginning of the settlement of the north of the peninsula by modern humans, which casts doubt, for the first time, on the possible sapiens origin of the drawings and introduces the possibility of a Neanderthal authorship.

Periodization of paleolithic art (cultures)

The different authors perform their own divisions and dates according to different criteria, so those shown in this graph are indicative.

Dating of the site

The dating of archaeological pieces found in the Altamira cave place, at least, Magdalenian man from 14,530 to 11,180 B.C. C. and the Solutrean around 16,590 B.C. C. But the absolute radiocarbon dating offers only dates, a position in time, so when we are talking about the lithic industry, paintings, etc., we refer to cultures, hence the discrepancy between authors when it comes to refers to terms such as Solutrean or Magdalenian. We even have to take into account the possibility of using different styles in a contemporary way, although other authors advocate evolutionary linearity. If the variation of dates of a certain style or culture according to the geographical area seems to be demonstrated, for example we should distinguish between Cantabrian Solutrense and Iberian Solutrense —in the rest of the Iberian Peninsula. In addition, to understand Paleolithic art it is necessary to study for a specific time and space, the different "schools" and their corresponding teachers with their particularities, which they influenced others. Édouard Piette said that "there has not only been a true art, but art schools". Therefore, schools should not be equated to temporal periods, since they are even recognized as contemporaneous:

Dates and periods related to Altamira... we accept the existence of plural times in which several graphic “traditions” develop in a way, more or less parallel, with tendencies in different aspects and even with the same thread for certain regions and attributes.Gárate Maidagán, 2008, p. 44.

Dates related to Altamira according to the different authors and according to the different methods.

Absolute dating of the paintings

The usual dating methods are not efficient for the majority of cave paintings since these, on the one hand, are not found in most cases in an archaeological context to which relative chronology techniques can be applied as would be the case. to a piece within a stratified deposit, and on the other, they do not allow the use of techniques such as C14 in non-organic materials. In the case of Altamira, there are two circumstances that have facilitated data collection: on the one hand, the black of the polychrome paintings, which is made of charcoal, and on the other, the fact that the cave was closed and inaccessible due to a landslide., which prevented subsequent work, and which, when dated to the Lower Cantabrian Magdalenian, makes all the engravings and paintings prior to it.

The carbon 14 method led researchers Laming and Leroi-Gourhan to propose a date between 15,000 and 12,000 years BC for the paintings in the Great Room of Altamira. C. Given that the Magdalenian of the Iberian Peninsula began 17,000 years BP (about 15,000 BC) and that until between 1,000 and 2,000 years later it did not become homogeneous throughout the territory, the paintings therefore belonged to the Magdalenian III period, according to authors framed in the lower Magdalenian and according to others in the upper one. Leroi-Gourhan includes the Altamira polychromes in period IV of his own taxonomy. The latest datings carried out have delimited the interval and indicate that the most probable date of the main set is from c. 13,540 BCE C., framed within the Magdalenian (between 15,000 and 10,000 BC), although the first representations are from the Gravettian and others from an intermediate time, the Solutrean (between 18,000 and 15,000 BC.). Subsequent to the archaeological work at Sautoula, sporadic collections and some planned campaigns have confirmed the existence of two levels of occupation, Upper Solutrean and Lower Magdalenian.

Bernaldo de Quirós and Cabrera gave fairly limited collected data in 1994:

"The data obtained have an average of 14 000 years BP [12 050 B.C.] for coal and 14 450 years BP [12 500 B.C.] for the humic fraction. For the tectiform figures of the “Cola de Caballo” attributed by A. Leroi-Gourhan to the Hl Style we have a dating of 15 440+200 (Gil’ A 91185) [13 490+200 a. C.]. Although the dates corresponding to the “Great Panel” are more recent than those that were possessed for the archaeological level of the entrance of the cave, 15 910+230 BP (1-12012) [13 960 a. C.] and 15 500+700 BP (M-829) [13 550+700 a. C.], these (sic) correspond with the dates corresponding to the tectiforms of the “Cola”. »Bernaldo de Quirós Guidoltí y Cabrera Valdés, 1994, p. 270.

Environment settings

Aurignacian

- Climate

It developed along the end of Isotopic Stage 3 (O.I.S. 3), around 40,000 years ago.

The Aurignacian climatology tends towards glacial conditions, with cold «peaks» of great climatic rigidity, and considerable instability (the climatology improves and worsens in relatively short intervals, up to less than a hundred years).

- Fauna

In the Aurignacian there was a more varied set of animals than in later times, since fauna from forest environments and “open environments” were combined, which were limited when the subsequent climate change left the Cantabrian area with a exclusively open landscape, conducive to deer and goats, main prey.

Solutrean and Magdalenian

- Climate

The Cantabrian Solutrean corresponds to the end of the French Würm III and the beginning of the Würm IV, with a sequence of temperate and humid climate, followed by cold and dry and ending with cool and humid.

The climate at the time would be very similar to today's Scottish climate —Cfb following Köppen's climate classification. For example, remains of limpets and periwinkles have been found inside the cave, which They were used as food and indicate a cold climate, in addition to the fact that the waters of the Cantabrian Sea were colder than today.

The Magdalenian, which extended along the Würm IV, had an alternating sequence of cold and dry and cool and humid climates. Climate change that occurred about 12,000 years ago modified hunting and eating habits, ending the Magdalenian with the transition to the Azilian.

- Flora

What is known is based on analysis of pollens, since there are no direct representations of the flora or remains of any of the parts of the plants at the time. From the studies it can be deduced that the landscape was open, really similar to the current one, with pines, birches, hazelnuts, oaks, ash trees and herbaceous trees.

- Fauna

The open environment was conducive to deer and goats, which were the main prey for the Altamira man of this time.

Due to the type of climate and geographical location, throughout the Würm a uniformity of species was maintained, although with variations in populations, which does not help with dating based on their remains, unlike what happened in other places where the weather changed more radically. For example, the deer and the ibex are the hunting species par excellence in the Cantabrian region, but since they can live from warm coastal climates to cold mountain climates, they are for them some very bad indicators.

Both the animals represented and those found in archaeological sites, with human occupation, are not indicative of abundance, since they could be due to a food, hunting or religious preference, although in the case of bone remains they must be related to a certain abundance for them to have been chosen as prey, especially those that have been detected as habitual. Through their remains, footprints or pictorial representations, direct evidence of a fox has been found, cave lion, lynx, deer, horse, wild boar, cave bear, ibex, chamois, roe deer, aurochs, bison, and at the coldest time, reindeer or seal. There are even mammoth remains. Of all these remains, the deer was the animal par excellence for hunting.

The Altamira man also extracted part of his food from the beaches, for example, limpet, periwinkle and scallop shells have been found. As for fishing, it was limited to river or estuary fish, such as trout, sea bass and, sporadically, salmon.

- Hominid

It was modern man, Homo sapiens, who painted the Altamira caves and made all the paintings and engravings found on the Cantabrian coast. The other inhabitant of the Iberian Peninsula, man of Neanderthal, it had been extinct for more than 13,000 years (c. 28,000 AP). Although the evidence collected at level 18 of the archaeological site of the El Castillo cave seems to demonstrate the coexistence of both Homo about 30,000 years ago, millennia before the first paintings in that cave and those of Altamira.

Prehistoric society and technology

The inhabitants of the Altamira area were nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes, made up of between 20 and 30 individuals, who used the natural shelters or entrances to the caves as their dwelling, but not their interior, and made use of fire for lighting and cooking. Excavations have led archaeologists to believe that during the Upper Paleolithic the fires were periodically cleaned and renewed, unlike the Middle Paleolithic where the fires were constantly maintained. In addition, there must have been a hierarchical social structure that allowed organizing hunting parties of large animals, since otherwise said prey would have been inaccessible without organization.

In the Solutrean, about 21,000 years ago, a new carving technique appeared, “flat retouching”, which allowed the creation of highly detailed instruments, such as projectile points. This technique, for totally unknown reasons, stopped being used at the beginning of the next period, the Magdalenian, and would not be resumed until 10,000 years later.

Among the tools produced during the Magdalenian, in addition to an improved lithic industry, are objects from the great revolution of about 17,000 years ago, such as bone industry, works in reindeer antler and bone, and an abundance of harpoons and needles sewing, an abundance that surely constitutes the most significant Magdalenian characteristic, although we must also highlight the manufacture of multiple tools such as the burin, the scraper, the firing pin, the perforated cane and the decoration of the thrusters, throwing weapons of spears and assegayas, known for millennia.

Prehistoric man hunted and consumed part of it at the hunting site, while the meatiest pieces, such as the limbs, were carried; in the Magdalenian period, caprids and deer were the preferred pieces. But on the other hand, they made objects that can be identified as ornaments, such as teeth or perforated shells.

The social structure is taken for granted to be able to organize work that must have been highly complex for the media that existed. As an example, one can imagine the Lascaux room with scaffolding and dozens of lamps illuminating it, in addition to maintaining the artist or artists at the expense of the labor of others until the creation of the temple and shrines is completed. From the studies of the living spaces, it has been possible to conclude that it was structured by functions: flint workshop, dismembering of game, skin treatment, kitchen, etc. And in the vestibule of Altamira, two wells were found that, most likely, were used to cook deer meat or other animals. It has not been possible to be sure if it was roasted or cooked since, although there are burned bones, they could have been thrown into the fire after eating it. elevated in society."

Archaeological site

The cave was inhabited for 22,000 years, some 4,000 before the main figures were painted. These data have been made possible by the study of notes and discoveries made by Breuil, Obermaier and others in the early XX century.

The cave has had several periods of archaeological excavation, after the first ones carried out by Sautuola himself, directed by important scientists in their respective times, such as: Joaquín González Echegaray, Hugo Obermaier, Hermilio Alcalde del Río. Significant dates of the history of the archaeological study of the cave are:

- 1876 - Visit and research of Sautuola. He discovered some of the paintings, but did not give them importance;

- 1879 - Excavation of the lobby and discovery of the large polychrome painting hall by the daughter of Sautuola;

- 1880 - Giner de los Ríos and Vilanova explored the cave;

- 1880 - Miguel Rodríguez Ferrer visited the cave, where they received him Vilanova and Giner de los Ríos;

- 1881 - Prospections of Harlé in the two visits he made. It was accompanied by Sautuola;

- 1902 - Excavaciones de H. Mayor del Río, y se documentaron por primera vez dos niveles: Magdaleniense y Solutrense. He collected three kilograms of hematites;

- 1902-04 - Prospections of E. Cartailhac and H. Breuil;

- 1924 - H. Obermaier and H. Breuil;

- 1925 - H. Obermaier;

- 1980-81 - J. González Echegaray and L. Freeman, last performed, and where only the mudaleniian stratum could be found.

- 2004 - for two days the previous excavations were worked and the results obtained so far were reinterpreted.

- 2012 - A sample of speleothemes for analysis by series of uranium offers dates of more than 35 000 years for some red records.

In them, what has been found is a large amount of habitation remains and movable art: handaxes, points, assegayas, scrapers, malacological remains —shells that were useful and food remains—, remains of ichthyofauna —fish bones—, beads, pendants, mammal remains —some decorated—, needles, burins, blades, airbrushes, decorated animal shoulder blades, in addition to many other sporadic or fortuitous prospecting and collections, such as the decorated perforated cane collected by Sainz in 1902. These pieces are scattered in public and private collections in France and Spain, and some of them have even been considered lost.

Paintings and engravings of Altamira

It is not possible to separate the painting from the engraving and vice versa, sometimes united in the same work and in others in works that share the space. In the case of Altamira, there are paintings, engravings and paintings with engravings, from different schools, styles or periods and of different technical qualities, as indicated above. It is important to understand that the habitation of the Altamira cave occurred over thousands of years and in non-continuous periods of time, hence the accumulation of styles and the differences between them.

The quality of the work in Altamira, like that of many other caves, assures us that the tools used, both for engravings and for drawings and paintings, were comparable to those used by artists from historical times. Thus, for example, the flint burins offer a very high cutting quality; and paints, putties and other pigments allow adaptation to the supports used, etc.

The evolution of art is not like that of technology, since it does not accumulate its innovations as, for example, a vehicle manufacturing process would. Although Paleolithic art has 20,000 years of development, it has not undergone an evolution of continuous improvement, one only has to think of the high quality of the very old figurines from the Aurignacian and Gravettian sites, long before the Altamira polychromes. Later examples of the non-linearity of the improvement we have in the Greek classics who made in marble a few thousand years ago the works that are still models to be followed by art today, when if art had followed a continuous evolution they would have been constantly replaced and would now look like shoddy remnants.

According to Breuil, the higher mudaleniense constitutes the moment of apogee in painting with the painting of modeling, which reaches its highest triumph in the polychrome figures of Altamira, where the history of art knew with astonishment to what degree of fidelity in the reproduction of Nature and to what height of artistic feeling man could arrive, in humble natural state, towards the fifteen thousand years before Christ.Obermaier, García and Bellido and Pericot, 1957, p. 105

Certain studies, with a high degree of subjectivity given the typology, have indicated that of Paleolithic parietal art only a part of around 15% of the figures represented have a high quality, while the rest would be mere drawings and paintings without "artistic" quality. Among the paintings that exceed this subjective threshold of art is, without a doubt, the ceiling of the Great Polychrome Hall of Altamira, for many authors, the masterpiece of the Magdalenian and even the Paleolithic.

Technique

The work, in a summarized and basic way, consisted of selecting the space, marking the contour with engraving, incorporating black and finally the color. The author had a firm and determined line, he knew anatomy perfectly of the animals he painted, in fact there are no rectifications of the drawing.

There seems to be an agreement that the "masters" who did the great work in the caves, such as the Altamira complex, existed and excelled, and also gave their drawings their personality. The work of the polychromes in the Great Room It is considered by Múzquiz, the author of several of the reproductions, as the work of a single author. It has come to be sure that the Altamira master painted in other caves, such as the El Castillo cave.

The superimpositions were treated, at first by Breuil, as a kind of stratigraphy that, together with the style, would allow the dating of the different works, paintings or engravings, but later studies concluded that many of them are simultaneous in time. Detailed studies of some sets of this type of palimpsest from different periods have concluded that the simultaneous superimpositions decreased with the advancement of time, becoming unusual at the end of the Magdalenian, reaching the omission of limbs or parts of the body to avoid them, although the authors of that time had no problem superimposing their work on that of other times. At that time, bison and horses are the animals least involved —according to percentage— in overlapping. For example, in the Great Room one of the bison has its head omitted to avoid overlapping with one of the boars, assuming that it is totally intentional since there is no prior carving of the area, so it was planned without a head from the beginning. Leroi-Gourhan came to consider the superimposition as a form of composition although he also recognized that this was not always the case as there were some diachronic superimpositions, leaving this compositional use for the synchronic.

Lighting

In order to carry out the works in the Great Room, and of course those in the interior, natural light was insufficient, so the author or authors had to use artificial light and more specifically fire. In many paintings, broken bones have been found under them, which is, for some of the experts, proof of the use of marrow as fuel for lamps. In modern tests it has been proven that this marrow with a wick of vegetable fibers produces a large, warm light and also without smoke or odors.

Pigments and painting supplies

The paint is made with mineral pigments of red iron oxide, ochres from yellow to red, and charcoal, mixed with water or dry, although some authors thought that animal fat could have been used as a binder. The black line outline of the figures was done with charcoal, which was also applied as a mass in regards to figures such as the polychromes in the Great Room.

The red color of the Altamira polychromes was achieved by applying wet hematite —if we accept the majority opinion that water is a solvent— on the ceiling, but although this pigment tends to turn brown when it dries, in this case the high The humidity of the cave prevented this from happening. In any case, the appearance of red varies according to the time of year due to the change in the humidity of the cave and the rock. that what is used is black and ocher in different gradations.

The application of the paint presents several possibilities, such as the application with the fingers directly, with some utensil like a brush, by means of fingers covered with chamois, or with a brush with chamois on the tip that allows loading paint and could provide a continuous stroke like that shown in most strokes, with a blunt-ended stick, and sometimes by blowing on the paint like an airbrush. This last case, that of the airbrush, has been almost completely proven, since in the excavations of Alcalde del Río three tubes made of bird bone were located on the surface and that they had remains of ocher both inside and outside. they found together with pieces of the aforementioned mineral, although it has not been possible to clarify with certainty if they were dry dyes or dissolved in water; nor have it been possible to date the three tubes or the fourth specimen that was found in the 1981 excavations.

Outline

The contour engraving was most likely made with a stone burin or similar, although no specific tools are known for this work.

Perspective, volume and movement

In different spaces and times, different perspectives were used. In the case of the Great Room, most of the polychromes are represented with what Breuil called “crooked perspective”, and which Leroi-Gourhan classifies within its type C or right biangular, which shows, for example, the bison's body in profile and the antlers in front, making each part seen from where it is most easily identifiable.

The sensation of realism is achieved by taking advantage of the natural bulges of the rock, which create the illusion of volume, through the vividness of the colors, which fill the interior surfaces (red, black, yellow, brown). and also by the technique of drawing and engraving, which defines the contours of the figures. In this way, the figures take advantage of the natural relief of the rock and sometimes model it internally to give an effect of volume and mobility, to which they add the selective scraping of certain areas to refine certain details, and the use of the two predominant colors, red and black, give images great mobility and expressiveness, and give paintings more volume.

Movement is expressed with different animation techniques according to styles and periods, within Altamira you can find from the "null animation" of some of the horses in the deep rooms to the "symmetrical animation" of the wild boar running at a "gallop" steering wheel" of the Great room, according to the cataloging of Leroi-Gourhan.

Description of the works

The artist(s) of the Altamira cave provided a solution to several of the technical problems that plastic representation had since its origins in the Paleolithic, such as anatomical realism, volume, movement and polychromy.

To position the works, the nomenclature used by Breuil and Obermaier in their work La Cueva de Altamira in Santillana del Mar (1935) is literally followed, although some that were not seen have been included until later. A detailed description is not made of all the elements found, which would add up to hundreds, but of those most visible or significant due to their time, technical quality, originality, etc. It must be taken into account that due to the nature of the medium and the type of works that were produced (engravings, paintings on engravings, superimposed paintings, etc.) still in the first decade of the century XXI new works continued to be discovered. Leroi-Gourhan has carried out a catalog that tries to differentiate drawings and engravings according to content, three types of elements: animals, ideomorphs and anthropomorphs. All three are represented in the Altamira cave.

Great Room

The Great Room, numbered I by Breuil and Obermaier, has been described many times, by authors as important as these two or García Guinea, as an unconnected set of individual figures, which could have caused that for many years nobody saw them as related groups, although authors such as Múzquiz and Saura and Leroi-Gourhan described the work as a great composition, and even Leroi-Gourhan as a possible message:

«The polychrome set of Great roof suggest a family of bison as they live today in the forests between Russia and Poland: males, females and small bisones, in different positions and attitudes. Some look to the outside of the group as if they protected him, and the sense of hierarchy... »Múzquiz Pérez-Seoane and Saura, 1999, p. 90

"...the pacifiers have the main characters of a message; they respond to the needs and means that man possesses from the Upper Paleolithic to forge manually realizable oral symbols. »Leroi-Gourhan, 1983, p. 44

They also recall the need to understand painting in its environment and indicate that the Great Room must have been conceived to be seen when entering from the outside through the access that connected it with the lobby. This position regarding the ceiling dealing with a single scene is discarded by some prestigious prehistorians, such as Ripoll and Ripoll, on the grounds that it is difficult to visualize the environment globally.

The ceiling of the room can be divided into three zones:

- The background of the room, beyond the Great Deer, where there are figures in red, in black, engraved, etc.

- The right area of the ceiling, with figures of animals in red, polychromes, engravings, etc.

- On the left side of the room is the large group of polychromes, for which the Altamira cave is really known.

Following the examination of the first gallery [...] we find the observer surprised to behold in the vault of the cave a large number of painted animals, apparently with black and red ochre, and of large size, representing mostly animals that, by their córcova, have some similarity with the bison.Sanz de Sautuola, 1880

The most represented animal is the bison. There are sixteen polychrome specimens and one in black, of various sizes, postures, and pictorial techniques, eleven of them standing, others lying down or reclining, static and moving on the left side, with sizes ranging between 1.40 and 1, 80m. Some theories indicate the possibility that the bison in a resting position really are injured or dead animals, or simply bison wallowing in the dust. In the years of study of the cave by Múzquiz in order to make copies of the cave ceiling, he discovered the existence of dozens of engravings of horses that must have been made by a single author and before the polychromes, since these are superimposed. Together with these specimens of bison and horses, there are deer, wild boars and tectiform signs. In addition there are scutiform symbols, so called because they resemble shields, which were most likely painted at the same time as the polychrome ones since they have the same ocher red as them.

As an example, three animal figures from the Great Hall are described in more detail:

The Shrinking Bison is one of the most expressive and admired paintings of the entire collection. It is painted on a bulge in the vault. The artist knew how to fit the figure of the bison, shrinking it, folding its legs and forcing the position of the head downwards, leaving only the tail and horns outside. All this highlights the spirit of naturalistic observation of its director and the enormous expressive capacity of the composition.

The Great doe, the largest of all the figures represented, is 2.25 m. It manifests masterful technical perfection and is one of the best forms of the Great Ceiling. The stylization of the extremities, the firmness of the engraved line and the chromatic modeling give it great realism. However, it accuses a certain distortion in its somewhat heavy invoice, surely caused by the close point of view of the author. Like almost all the figures in the room, it is engraved in a large part of the details and the outline. Below the neck of the doe appears a small bison in black outline, and at her feet the herd of bison is displayed.

The ochre horse, located at one end of the vault, was interpreted by Breuil as one of the oldest figures on the ceiling. The horse remains immobile and there is only a presence of black in the mane and part of the head. Inside you can see the drawing of a deer, also in red. This type of pony must have been common on the Cantabrian coast, as it is also represented in the Tito Bustillo cave, discovered in 1968 in Ribadesella.

Other rooms and galleries

Carrying out a linear route, we find gallery II and room II of the plan where there are works on the clay of the ceiling known as macarroni and also a possible bull or aurochs. Room III, a diverticulum, it is known as the "Room of the Tectiforms" because a large number of them are red on projections of the ceiling. Gallery IV is reached, with superimposed engravings of deer and hinds and highlighting a doe with unfinished legs., giving way to the long gallery V with the drawing of a black bison without legs, the engraving of a bull and a possible horse painted in black. To the left is a nook identified as room VI with an important black bison. The widening between rooms VII and VIII includes what Breuil and Obermaier called zone C, left wall as we move towards the back, with elementary drawings in black and signs and lines, and zone D, on the right, with elementary drawings in black and more signs and lines.

We arrive at a larger room, Room IX, known as the "La Hoya Room." It is the last room before reaching the Horsetail. On the left, before entering the final corridor, known as zone E, there are four animal representations, from left to right: a goat (possibly an ibex), a doe and two more ibex, executed in black and which have been assigned to the Lower Magdalenian. In addition, there is a black painting of an indeterminate quadruped. Gallery X is known as "Cola de Caballo". It is a narrow corridor about two meters wide where up to nineteen paintings and engravings are found: bison, deer's head, horses and bovids. Some are only sketches and others are complete, with sizes around 30 cm and reaching 50 cm. Tectiforms are also found.

Iconography and meaning

The cave representations of Altamira could be images of religious significance, fertility rites, ceremonies to encourage hunting, sympathetic magic, sexual symbology, totemism, or could be interpreted as the battle between two clans represented by the doe and the bison, without ruling out art for art's sake, although this last possibility has been rejected by some scholars since a large part of the paintings are found in places that are difficult to access in the caves and therefore difficult to exhibit.

The following table summarizes some of the interpretations that have been given to rock art by some of the authors who have most influenced the studies (main source Pascua Turrión, 2006):

| Ord. | Authors (date) | Explanation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lartet and Christy (1865-1875) Piette (1907) | Art by art | |

| 2 | Reinach (1903) | Magic - religion | |

| 3 | Durkheim (1912) | Magic - religion | |

| 4 | Breuil (1952) Bégouën (1958) | Magic - religion | |

| 5 | Ucko and Rosenfeld (1967) | Media: multiple cause | |

| 6 | Leroi-Gourhan and Lamming (1962-71; 1981) | Structuralism | |

| 7 | Clottes and Lorblanchet (1995) | Magic - religion | |

| 8 | Balbin and Alcolea (1999-2003) | Media: multiple cause | |

| 9 | Lewis-Williams and Dowson (1988-2002) | Chamanism by altered states of consciousness |

In any case, although the difficulty of knowing what motivated Paleolithic man to create these works of parietal art is obvious, it can be affirmed that the realization of the paintings responds to planning, which implies a cognitive process of reflection to conclude what to paint, where and how to do it, and distribute it; and there is almost agreement that they are symbols linked to hunting and fertility. The need for a social organization to be able to carry out works of this magnitude also seems clear:

"...the motive to interpret does not correspond to an individual will but to a social will. The impeccable solution of the figures makes us think about the selection of the person who performs them and the importance of it for the other members of the tribe. »Múzquiz Pérez-Seoane, 1994, p. 359

Leroi-Gourhan, based on other studies and his own, has concluded that the caves were temples —public space— that contained some sanctuaries —space intended only for certain people— and that they must be understood as a whole, with an iconography based on the types of animals and their position in the panels —groupings of figures—, and of these in the cave. Prehistoric man did not capture a collection of edible animals or common prey, rather it was a bestiary, as shown by the discrepancy between what was represented and the food remains found. In the case of Altamira, the Great Room would be the temple.

Protection and dissemination

Since its discovery and its subsequent recognition, the cave has had different levels of national and international protection, which have become extreme, prohibiting the visit, due to the wide social diffusion, which made it a massive tourist destination.

Since the Santillana del Mar City Council created a Cave Conservation and Defense Board in 1910, the way to protect it has gone through different phases: opening to the public in 1917, now with a guide; in 1924 it was declared a Historical-Artistic Monument; a year later a Board was appointed to improve conservation conditions; 1940 was the year the Cueva de Altamira Board of Trustees was set up; in 1977 it was closed for the first time after a study and in 1982 it reopened on a limited basis, for 8,500 annual visitors; 1985 was the key year of worldwide recognition when it was named a World Heritage Site; and in 2001 the Museum and replica were opened together with the original, although the debate on visiting the original has not been closed.

World Heritage Site

The Altamira Cave was declared a World Heritage Site by Unesco in 1985. Later, in 2008, protection was extended to another 17 caves with human remains (perhaps the best preserved and representative of a larger known group as Paleolithic rock art from northern Spain).

Cave access and replicas

In 1917 the cave was opened to the general public and in 1924 it was declared a National Monument. From that moment on, visits would increase, but during the 1960s and 1970s, the many people who accessed to the cave endangered its microclimate and the conservation of the paintings, for example, in 1973 the figure of 174,000 visitors was reached. In this way, a debate was created about the advisability of closing Altamira to the public, even reaching the debate in the Congress of Deputies. In 1977 the cave was closed to the public to finally reopen in 1982 and allow access to a restricted number of visitors per day, avoiding exceeding 8,500 per year.

The large number of people who wanted to see the cave and the long waiting period to access it (more than a year) led to the need to build a replica. Since 2001, the National Museum and Research Center of Altamira has been built next to the cave, the work of the architect Juan Navarro Baldeweg. Inside, the so-called Neocueva de Altamira stands out, the most faithful reproduction of the original that exists and very similar to as it was known about 15,000 years ago. In it you can see the reproduction of the famous paintings of the Great ceiling of the cave, carried out by Pedro Saura and Matilde Múzquiz, professor of photography and tenured professor of drawing at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the Complutense University of Madrid, respectively.. The same techniques of drawing, engraving and painting used by Paleolithic painters were used in this reproduction, and the copying was carried to such an extent that new paintings and engravings were discovered during the study of the originals.

There are two other reproductions of the paintings made simultaneously from a work by Pietsch in collaboration with the Complutense University in the 1960s, one is in an artificial cave made in the garden of the National Archaeological Museum of Spain and the other in the Deutsches Museum in Munich. In Parque España in Japan—an amusement park themed on Spain—a partial copy of the paintings in the Great Room executed by Múzquiz and Saura and inaugurated in 1993 is exhibited. Teverga Prehistory Park in Asturias, there is a faithful partial reproduction of the Great Roof by the same authors.

In 2002 the cave was closed to the public pending the commissioned impact studies. In the first decade of the XXI century, there was a wide debate about whether or not to reopen the cave to the public. The Ministry of Culture commissioned a study on the state of the paintings and the advisability of scheduling visits, which was made public in 2010. In June of that same year, some news indicated that the Board of Trustees of the Altamira Cave confirmed that it would be reopened, to despite the fact that the CSIC recommended otherwise in its conclusions. Finally, it was not opened on that date and in August 2012 it was announced that a study would be carried out on the impact of the visits, while they were limited to the study itself and special permits.

The caves were reopened to the public on an experimental basis from February 26, 2014 until August of the same year, with entry limited to just five visitors per day and 37 minutes to assess the impact.

Social impact

The Paleolithic art of the Altamira cave has had an influence in the social field, beyond what it has had for prehistoric studies. For example, in the world of painting, it gave rise to the creation of the Altamira School of modern painting; and Picasso, after a visit, exclaimed: "After Altamira, everything seems decadent." Although other artists from branches several also understood the importance, so Rafael Alberti wrote a poem describing the sensation of the visit he made; in 1965 the character Altamiro de la Cueva was created, which gave its name to the comic of the same name, where the adventures of a group were narrated of prehistoric cavemen, shown as modern people but dressed in loincloths; rock band Steely Dan composed a song titled "The Caves of Altamira" on their album The royal scam (1976).

Some of the polychrome paintings in the cave are well-known prints in Spain. The logo used by the autonomous government of Cantabria is based on one of the bison in the cave as a tourist promotion. The bison has also been used by the cigarette brand Bisonte, and since 2007, it is one of the 12 Treasures of Spain. In 2015, the National Currency and Stamp Factory of Spain issued a commemorative coin euro coin from its UNESCO World Heritage series with the figure of an Altamira bison.

On April 1, 2016, the film Altamira was released, directed by the British Hugh Hudson and starring the Spanish actor Antonio Banderas, which tells the story of the discovery of the cave and the problems for its acceptance. Despite the ambition of the project, and its public support and promotion, the critics were not very favorable, and in fact the collection in its first week of exhibition was not what was expected.

On September 24, 2018, the Google search engine honored the Altamira cave with a Google Doodle, visible from Spain and some Latin American countries.

Contenido relacionado

Convent of San Marcos (León)

Frederick William IV of Prussia

27th century BC c.