Almoravids

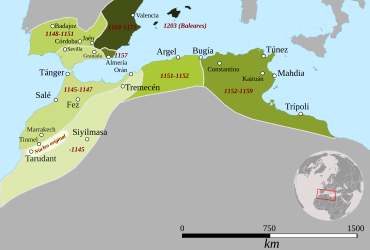

They are known as Almoravids (in Arabic, المرابطون [al-murābiṭūn], and this from the singular مرابط [murābiṭ], that is, «the marabout», species from hermit and Muslim soldier, 'Marabout' in French) to some monk-soldiers who emerged from nomadic groups from the Sahara. The Almoravids embraced a rigorous interpretation of Islam and subjected large swaths of the Muslim West to their authority, forming an empire centered on Morocco, between the 11th and 12th centuries, which came to extend mainly through present-day Western Sahara, Mauritania, Algeria, Morocco and the southern half of the Iberian Peninsula.

Religious and political movement that emerged among the Cenhegi Berbers of Western Sahara, nomadic tribes and camel drivers, managed to spread through the western Maghreb, unify the territory of modern Morocco for the first time, spread through al-Andalus and implant a unique variant of Islam in the region, Maliki Sunnism. Its expansion through the Maghreb meant the end of the supremacy of the traditional rivals of the Cenhegi, the Cenete Berbers, who had dominated the region until then, and the victory of the nomads over the sedentary inhabitants of the area. The defense of religious orthodoxy, which satisfied the influential Islamic jurists, and the abolition of non-canonical taxes, welcomed by the general population, facilitated Almoravid expansion.

With his arrival in the Iberian Peninsula in 1086, a long period of Andalusian history began, characterized by the intervention of three Maghrebi dynasties (those of the Almoravids, the Almohads and the Benimerines), between whose successive hegemonies there were periods of peninsular reaction (the kingdoms of taifas). The Maghrebis, until then in a position of inferiority compared to the Andalusians, came to dominate the region, thanks to their ability to form a centralized state that could resist the attacks of the Christian states of the north peninsular. These Maghrebi interventions in the Iberian Peninsula that began with the Almoravids gave rise to almost a century and a half of union between Iberian and Maghrebi Islam.

The rapid expansion was followed by a rapid decline, due to the lack of solidity of the new empire. The heyday and the beginning of the decline, due to the Almoravid inability to stop the expansion of the Iberian Christian states, to the The rise of Andalusian discontent and the unstoppable expansion of the Almohads occurred during the long reign of the third emir, Ali ibn Yúsuf. While the campaigns in al-Andalus against the Christian states absorbed a large part of the military power of the Almoravid Empire, in the Maghreb arose a rebel focus in the mountain population, Masmudí, the Almohad movement, which ended up destroying it. The discontent of the population due to the great power of the Maliki alfaquíes, the abuses of the soldiers and the increase in taxes also contributed to the fall to maintain armies.

Etymology

The term «Almoravid» comes from the Arabic al-murabitun (المرابطون), the plural form of al-murabit meaning literally "the one who binds himself" and figuratively "he who is ready for battle in the fortress". The term is related to the notion of ribat, a border fortress-monastery, from the root r-b-t (ربط [rabat]: «atar»; or رابط [raʔabat]: "to camp").

It is uncertain when or why the Almoravids acquired this name. Al-Bakri, in a writing from the year 1068 prior to his peak, already called them al-Murabitun, but he did not clarify the reasons for it. Writing three centuries later, Ibn Abi Zar suggested that it would have been previously chosen by Abdallah ibn Yasin because, finding resistance among the Gudala Berbers of Adrar (Mauritania) to his teachings, it took a handful of followers to erect a makeshift ribat (monastery-fortress) on an offshore island, possibly Tidra, in the Bay of Arguin. Ibn Idhari wrote that the name would have been suggested by Ibn Yasin to mean "to persevere in the fight", to encourage morale to fight a particularly difficult battle in the Draa valley around 1054, in which many casualties took place. Whatever the correct explanation, it seems certain that the name was chosen by the Almoravids themselves, partly with the conscious aim of preventing any tribal or ethnic identification.

It has also been suggested that the name could be related to the ribat of Waggag ibn Zallu in the town of Aglú (near present-day Tiznit), where the future Almoravid spiritual leader Abdallah ibn Yasin received their initial training. Moroccan biographer of the 13th century Ibn al-Zayyat al-Tadili and Qadi Ayyad before him in the XII pointed out that the Waggag educational center would be called Dar al-Murabitin ("The House of the Almoravids"), and which may have inspired Ibn Yasin's choice of the movement's name.

Contemporaries often refer to them as the al-mulathimun ("the veiled ones", from litham, Arabic for "veil"). The Almoravid veiled below the eyes, a custom adapted from Cenhegi Berbers that can still be found among modern-day Tuaregs, but unusual further north. Although practical for desert sand, the Almoravids insisted on wearing the veil in anywhere, as an emblem of difference in urban settings, partly as a way of displaying their Puritan credentials. It served as the uniform of the Almoravids, and under their tenure, sumptuary law forbade anyone else to wear the veil, making it the distinctive garment of the ruling class.

Rise of the Almoravid movement

The Cenhegies

The Almoravid movement arose in the inhospitable territories that stretch between the last cultivated areas of southern Morocco and the plains of the Senegal and Niger rivers. The region was inhabited only by groups of Berber nomads who did not practice agriculture. Their only wealth came from the herds they kept and the income they earned from offering protection to the caravans that crossed the territory.

In the southern lands corresponding to the current states of Mauritania and Mali, from the Senegal River to the Niger River, bordering the former black kingdom of Ghana, a people of nomadic Berber herders had settled with their cattle, belonging to the Zanhaga confederation (the Cenhegíes), whose main tribes were the Lamtuna and the Masufa (other Cenhegí tribes, these sedentary, inhabited the valleys near the Atlas, such as the Draa river; among these were the Lamta and the Gasula). The Cenhegi of this area were related to the Zirids of Ifriqiya, and distinguished themselves from other Berber groups, such as the Masmuda of the Atlas and the Cenetes of northern Morocco.

These desert cenhegis had become slightly Islamized by the X century, through contact with Muslim merchants who, since Siyilmasa, traveled the caravan routes across the desert to Audagost and the Ghana Empire to barter their goods for gold. Between the 9th century span> and the XI, three of the region's distinct Cenhegi tribes—Lamtuna, Masufa, and Gudala—formed a confederation, which dominated the Lamtuna tribe, the southernmost of them, which covered a wide area between the Draa and the Niger. The objective of this league was to stop the advance of the black peoples of the south, keep the city of Audagost, dominating a large grazing area and controlling the main caravan routes that crossed the region from north to south. In the XI, the tribal league, which had been in disarray during the previous century, was remade. the Gudala related by marriage to the Lamtuna, Yahya ibn Ibrahim, architect of the rise of the Almoravid movement. By then the Cenetes of the Magrawa tribe, traditional rivals of the Cenetes, had wrested control of the caravan routes that stopped at Siyilmasa and Audagost and the important pastures of the Draa Valley.

Religious awareness: foundation of the Almoravid movement

Possibly around 1035-1036, the chief of the Cenhegi Berber tribe of the Gudala Yahya ibn Ibrahim made the pilgrimage to Mecca. Back home, he crossed Egypt and Ifriqiya, where he met a renowned alfaqi (fqih 'learned in Islamic law') from Kairouan, Abu Imran al-Fasi, a native of Fez and a follower of Malikism. Thanks to He became aware of his religious ignorance and the superficial knowledge that his tribe had of religion, and asked the teacher to send one of his disciples with him to instruct his Gudalí compatriots. Convinced that his disciples of the city would not wish to settle with the caravan tribes of the desert, Abu Imran proposed that he consult a former pupil who preached in a territory dependent on Siyilmasa. Abu Imran proposed for this task Uaggaq ben Zellu al-Lemtí, of the tribe of the Lemta, who in turn recommended Abdallah ben Yasin al-Gazulí, of the Cenhe tribe gí of the Gazula. The latter, who left with Ibn Ibrahim, fell the role of preacher within the Cenhegi tribes. His mission was to instruct them in the prescriptions of Islamic law according to the Sunna and the Maliki legal school. This entailed complicated social reform and local customs, which proved difficult.

The Maliki school was rigorist and defended the literal interpretation of the Quran. also to the caliphate. This religious reform was oriented to the benefit of Sunnism and Malequismo, of which the new preacher and spiritual guide Abdalá Ben Yasin was a staunch defender, endowed with exceptional vigor. His intellectual baggage was, in reality, little, but his religious knowledge stood out from the low level of the members of the tribes, superficially Islamized. The doctrine he preached would soon take on a political color, with a return to Sunni orthodoxy and a rigorist look. with a group of some sixty or seventy volunteers, who submitted to his inflexible ascetic rigor, very different from the relaxed traditions of camel-driver life. The reform, too radical, and certain theological contradictions allowed his local rivals to wrest control of the tribe's assets, which he had had since his arrival in the region, and to discredit him. Ibn Ibrahim's death had deprived him of his protector and left him at the mercy of his followers. opponents in the tribe, who criticized his greed - he seized a third of the converts' possessions as a "purification" of the rest of the goods - and his brutality in the application of punishments. Ben Yasin then withdrew with a handful of followers of a rabid that he founded on a coastal island —Tidra or Targuin— close to the tribe's territory.

This rábida —a kind of military convent— was considered a place of purification and training for the exemplary Muslim. This exemplary character was achieved on the basis of iron discipline. Its members acquired a proselytizing and bellicose spirit due to the religious ardor that was fostered. This exemplary character, along with the propaganda made by his followers, made the reputation of Abdalá ben Yasin and his rabida grow along with the number of monk-soldiers who came to the place to be purged. The doctrine inculcated by Ben Yasin, not very subtle in theological terms, was that of a simple Malikism, adapted to the mood of the disciples.

The movement's first push was due to the success of its raids into Lamtuna territory, which allowed it to gain significant loot. A decisive moment in the expansion of the movement was the accession of Yahya ibn Umar al-Lamtuni, head of the powerful Cenhegí tribe of the Lamtuna (tifawat, lemtuna or lemtana means veiled men), and his brother Abu Bakr. The tribe's support for Ben Yasin later allowed him to dominate the Almoravid movement, having formed its initial nucleus. Men had the custom of wearing a double veil—the upper one, the niqab, the head and forehead, and the lower one, litam, for the neck and face. This separation of powers between the military and the religious chief persisted until Yusuf ibn Tašufin's seizure of power. The pious and submissive Ibn Omar, a military veteran, was the instrument that Ben Yasin used to achieve territorial expansion by arms. This began when the religious community reached a sufficient size to try to force its religious beliefs on tribes who had initially rejected Ben Yasin's reforms. The Almoravid conquest, sustained by the religious impulse of the community founded by Ben Yasin —with Puritanism as its main characteristic—, also had economic motives —aspiration to improve the economic situation and control richer territories— and cultural ones, since it confronted the nomads of the Sahara with the sedentary populations of the north, to the Zanhaga tribe with its traditional rival, the Zeneta. Resisting tribes lost a third of their possessions when they were subjugated.

Conquest of the desert and bordering regions

Situation in the Western Maghreb

During the X century, the Umayyads of Córdoba had challenged the Fatimids for control of the western Maghreb, and with it, that of the trans-Saharan routes and the gold that came through them to the north of the continent. In general, this fight was carried out indirectly, through Berber groups that were clients of the two enemy caliphates: normally the Cenetes were allied with the Umayyads and Cenhegis Zirids linked to the Fatimids. The disintegration of the Cordovan caliphate did not end the conflict, but rather caused a series of Cenete principalities to take its place. These clashed with each other and with the Zirids to the east. the continuous struggles affected the economy of the region, which entered into crisis. Kharijites.

First military campaigns

The first military campaigns to forcefully impose the religious and social reform they advocated took place around 1049-1050 in the coastal areas of Senegal. They first attacked the Gudala, who roamed the regions near the sea and who had previously expelled Ben Yasin. Defeated the Gudala and joined the movement, Ibn Omar then went against the Lamtuna, his own tribe. Subdued these also in the fighting in the Adrar, the offensive continued to the southeast, against the Banu Warit, and then against the Masufa and the rest of the Cenhegi tribes located between the Saguia el Hamra and the middle Niger. Around 1052, the forced unification of the Cenhegi tribes must have been completed. They dominated the desert and Once the tribal confederation was united, the Almoravids prepared to launch themselves against Morocco, of which the Cenetes were lords at that time. Precisely the disgust of part of the population with the chaotic situation created by the pr incipientes of the Cenetes facilitated the expansion of the Almoravids.

Submission of the pre-Saharan zone

Next, the Almoravids began the conquest of the oasis area of Tafilalet and Draa, close to the desert from which they came. The conquest was not easy and the Cenhegi tribes of the region resisted valiantly. In 1052-1053, the Almoravids finally subdued the Targa and Lamta in the area, and added them to their cause. It seems that it was at this time that Ben Yasin began to call his followers Almoravids, either because the movement had been forged in the rábida (ribat, from which marabout or al-morávide derives), either from the Arabic term rabitu, uniting with others to fight.

Owners of the left bank of the Draa, the Almoravids were already threatening Siyilmasa, the main caravan center of trans-Saharan trade and oases in the area, one of the largest cities in the Maghreb and dominated by the Zeneta tribe. Called by the spokesman for The jurists of the region, who complained about the oppression of the Cenetes, the Almoravids conquered the city. To do this they counted on their fast contingent of camel drivers and the sympathies of the Cenhegi tribes subject to the Magrawa Cenetes of Siyilmasa. they defeated the emir of the town, who had refused to submit, and then, at the end of 1053, surrounded the city before taking it by storm.

Ben Yasin imposed his rigorous religious system on the conquered city: taxes that were not provided for by Islamic law were abolished —always a very popular measure—, musical instruments were prohibited, shops that sold wine were closed, and a fifth of the booty obtained among the lawyers who had called on the Almoravids to their aid. Their religious puritanism spread in tandem with their territorial expansion. The three main urban centers controlled by the Almoravids were then Siyilmasa, Aretnena, nearby to Audagost, and Azugui, north of Atar. The latter, founded by a brother of Yahya ibn Umar al-Lamtuni in the northern part of Lamtuna territory, was the center from which the first Almoravid military expeditions departed and remained the capital southern dynasty.

Fighting in the south and Siyilmasa uprising

Once they took possession of the area of pre-Saharan oases, land of water and pastures that improved their economic situation, the Almoravids turned against the black kingdoms of the south, Takrur and Ghana, traditional enemies of the Cenhegis who at the beginning of the century Audagost had been taken from them by the 11th century. This was a prominent trading center, part of the caravan route, and a place hotly contested by the Black States to the south and the Berbers to the north. In the second half of 1054, the Almoravids attacked the city and took it by storm. By dominating Siyilmasa and Audagost, they gained control of the caravan routes of the region. Two years later, they began minting their own dinars at the Siyilmasa mints. Territorial expansion ceased when the Siyilmasa rebelled, where the bulk of the population, discontent with the rigorous Almoravid rule, passed through weapons to the unsuspecting garrison. The Magrawíes Cenetes temporarily recovered the lordship of the region.

Ben Yasin ordered the regrouping of the tribes to retake the lost city, but the Gudala, who felt neglected by the Lamtuna, ignored the call and returned to their coastal territories. In a battle between the Gudala and the Almoravids in 1056, Ibn Omar perished, at a time of grave crisis for the movement. At the same time, however, his brother, Abu Bakr ibn Omar, recaptured Siyilmasa in May 1055, with his own forces and those contributed by Ben Yasin, recruited from the Targa and Sarta tribes, subject until recently to the Cenetes. This victory caused the Almoravid military command to pass from the late Yahya to his brother Abu Bakr.

Conquest of southern Morocco

Submission of Sus

Before embarking on the conquest of the Moroccan mountains, the Almoravids took over the regions that extend to the south at their feet. They advanced towards the caravan center of Nul Lamta from Siyilmasa, through a territory that, populated by the Gazula and the Lamta, proved favorable to them. The city surrendered without resistance, in late 1056 or early 1057. They then headed towards the Sus plains, where they conquered the region's capital, Taroudant. of resistance to the conquest were those places populated by Cenetes, among which were Massa and Taroudant itself, inhabited by Magrawí Cenetes. In a year of campaigning, the Almoravids seized about ten thousand square kilometers, limited by the sea to the west, Tafilalet to the east, the Draa to the south and the Sus to the north.

Penetration into the Anti-Atlas was not difficult either, since other Cenhegi groups populated the region, who joined the Almoravids without misgivings.

Conquest of the Upper Atlas

In 1057, penetration into the Atlas region, dominated by the Masmuda, began. Advancing from Taroudant towards Agmat, easily dominating the different Masmudid groups they encountered, the Almoravids reached the Sisawa boulevard and the population of the same name, which they took by force. They then turned towards the sea, abandoning the advance towards the northwest that they had maintained until then and, subduing several more tribes, crossed the plain of Hawz in the direction of the Naftis valley. The city of the same name, controlled by the Masmudids, submitted to the Almoravids at the end of 1057 or the beginning of the following year. In a few months of campaign, they conquered the territory limited by the wadi Tensift to the north and the Sus to the south and from wadi Naftis to the sea.

Next, they headed for Agmat, populated by Masmudis, but ruled by a Magrawí who was not well liked by the Masmudí population, who sided with the Almoravids. The local Magrawís, on the contrary, they resisted the conquest, which, however, they could not prevent. The region was rich and abundant in trade, numerous palm groves and cattle, and was weakly dependent on the Banū Ifrēn lords of Salé. Ben Yasin from the hard campaign of the previous months through the western Atlas. Before attacking the Ifranis of Tadla, during the summer they carried out a raid to secure the route from Siyilmasa to Agmat in which they subdued various Masmudid groups without encountering resistance. Among the conquered towns was Ouarzazate, the main square of the Haskura Masmudids. Ben Yasin's marriage to the daughter of a Masmudid chief from Agmat also facilitated the subjugation of large areas of l Southern Morocco, populated by this tribe.

Subjugation of the coastal plains

At the end of the year, the campaign began to seize the high alluvial plains of Tadla, dependent on the lordship of Salé and where the defeated Magrawi lord of Agmat had taken refuge. After overcoming some resistance, the Almoravids penetrated into the region, advancing in a northeasterly direction. There they fought with the Ifranis and the Magrawis, whom they defeated, taking control of the territory.

After taming the Tadla, the Almoravids launched themselves to fight the Barghawata Masmudis, who were considered heretics. They ruled the Atlantic plains at the foot of the Middle Atlas up to the mouth of the Bu Regreg and some Cenete groups of the region and they had large forces - some twenty-two thousand horsemen - to face the invading hosts of Ben Yasin. The Almoravid invasion began in the spring of 1059, after crossing the Umm Rabi, a river that bordered the Tadla on the north and the domains of the Barghawata to the south. Overwhelming the different Cenete groups with whom they crossed paths, they reached the coast. The fighting with the Barghawata was fierce and both sides suffered numerous losses. The Barghawata resistance It was fierce, but the Almoravids managed to progress northward. In one of the battles fought during June or July 1059, however, Ben Yasin was killed. It was a significant loss for the Almoravids. ravids for being the spiritual leader and founder of the movement and he was succeeded in office by a trivial figure of whom only his name is known: Sulayman ibn Addu. He died shortly after, also in the fight against the Barghawata who, after Despite everything, they were finally defeated.

Reorganization, Masufa rebellion and brake to the conquest

With the almost simultaneous disappearance of the religious leaders, the political element of territorial expansion and subjugation of the cenetes within the Almoravid movement was accentuated, and the religious one lost strength.

In the winter of 1059-1060, the Barghawata having been defeated but the Almoravids weakened by hard fighting, Abu Bakr returned to Agmat, the first Moroccan capital of the Almoravid state —since approximately 1067. In the following spring, his hosts attacked the cenetes of the central Atlas, in the Fazaz region, and took possession of it ephemerally.

After this campaign, the advance through Morocco was interrupted by the rebellion of the Masufa, jealous of the supremacy of the rival Lamtuna, who held command of the Cenhegi confederation. Abu Bakr ceded the government of the territories conquered in Morocco to his cousin Yúsuf ibn Tašufín and left Agmat to the south to face the rebels in 1071.

Abu Bakr managed to bring the rebels back to obedience, but his activities halted the advance in the north for two years, as the forces he had left to his relative were meager to continue the conquests in the face of increasing resistance from the rebels. enemies. Upon Abu Bakr's return to Agmat, Ibn Tašufin refused to return him to power and managed to make him resign and go to the desert, to fight the black kingdoms of the south, instead of unleashing a new fight within of the Almoravids such as the one that had just faced the Masufa and the Lamtuna. Abu Bakr remained nominal head of the movement until his death in 1087, and coins were minted in his name, although power had passed to Ibn Tašufin.

Unlike the Cordovan Umayyads and later Almohads, neither Ibn Tašufin nor his successors at the head of the Almoravid State proclaimed themselves caliphs, but were content to arrogate to themselves a lesser title, that of "prince of the believers" (amir al-muslimin).

Military System

Although it is claimed that the Almoravids could muster up to 30,000 soldiers, their armies generally constituted much smaller forces. The sources mention a host led by Abu Bakr in 1058 consisting of 400 knights, 800 camels and 2,000 peons. The bulk of the forces came from the Lamtuna, Masufa, Gudala, Gazula, Lamta and Masmuda tribes from the plains.

Most of the Almoravid soldiers were infantrymen who fought in ranks, the first with long lances —to avoid cavalry charges—, the next, armed with javelins —which could pierce armor— Both the cavalry and the the infantry carried shields - made from the skin of a desert antelope and famous for their resistance - and sabers. The knights also wore cuirasses. The standard bearers always went before the first lines, to encourage the troops; Drums were used for the same purpose, which also served to communicate between the different units and to intimidate the enemy. The source of their weapons were the artisans of the Adrar and Draa regions, whom they had subjugated. His armies were very effective in the open field, but they lacked experience in polyorcetics, which was a disadvantage when they had to face the conquest of well-defended places, such as Aledo, Toledo or others in al-Andalus. Ibn Tasufín, in addition to Being the first to hire mercenary forces, such as Turkish archers, and buy slaves for his units, introduced another important change: the substitution of the camel for the horse as the main mount of the Almoravid soldiers. of the desert, it had played a fundamental role in the first Almoravid campaigns, it was lost in favor of the horse in the conquest of Morocco and in the combats in al-Andalus. The use of closed cavalry formations was an Almoravid war innovation, as cavalry combat in Europe used to be singular. Europe.

The fleet appeared late, around 1081-1082, when the Almoravids needed to attack Ceuta and decided to intervene in al-Andalus.

Most of the campaigns, as it happened throughout the Middle Ages, were carried out in the milder seasons of the year; rare were those undertaken in winter. The bulk of the fighting took place between May and October.

Central military command was left in the hands of some chiefs of the Lamtuna tribe, although minor posts were sometimes given to chiefs of other subject tribes. This cohesion of the ruling group prevented serious dissensions and rebellions by the Lamtuna tribes. warlords who commanded the Almoravid hosts, but it limited the appeal of the movement for other leaders outside this small circle, since they knew that they could not reach the key positions in the Almoravid state.

The Almoravid governors of al-Andalus did not have the favor of the population. Paradoxically, the exclusion of the Andalusians from military affairs, together with the administrative inexperience of the Almoravid chiefs, favored the influence of the older Andalusian families. powerful in civil administration.

Abu Bakr's campaigns against black states

In 1063 Abu Bakr undertook the fight against the Ghana Empire, which stretched between the Atlantic and Timbuktu and had a series of vassal states around it. It took him ten or twelve years of continuous campaigns to subdue Takrur and take in 1076 the capital of the empire, Kumbi Saleh, which he sacked. This victory put an end to the rival empire. Eliminated this, the Almoravids continued their advance to the east, towards the Niger. Almoravid control of the area, however, it was temporary. The death of Abu Bakr in 1087-1088 once again disrupted the union of the Cenhegi confederation, which never recovered, and allowed the black populations of the south to shake off the Almoravid yoke; These formed new states that threatened the Cenhegi groups of Audagost and Adrar, although with less force than before. The death of Abu Bakr marked the end of both the confederation from which Almoravid power had emerged and the mainly religious phase of the movement. The center of this shifted from the desert to the north, to Morocco.

Conquest of northern Morocco

After founding the new capital of Marrakech —first as a mere military camp from which to launch the new campaigns— in a strategic place between the sea and the mountains, laying the foundations of the State Administration and reorganizing the Army, Ibn Tašufín resumed territorial expansion in early 1063. He first headed for Fazaz, besieged its capital, Qalat Mahdi, which held out for nine years, and defeated various Cenete groups in the Sais plain, south of Fez. and Meknes. He forced the Hamadids who controlled Fez to lock themselves in the city, after beating them. Unable to take the city at first, he marched against Sefrou, which he conquered. After concentrating his forces again before Fez, the Almoravids finally managed to seize it, between June and December 1063. Between that year and 1070, the Almoravids conquered all of northern Morocco with the exception of Ceuta and Tangier.

While Ibn Tašufín was campaigning in the north, however, the former Magrawi lord of Fez managed to recover it with a coup and had the Almoravid garrison that remained to guard it assassinated. Next, the lord of Fez he defeated and killed the Meknesian, who had submitted to the Almoravids. The Almoravids tried in vain to recapture Fez and had to content themselves with besieging it; the siege lasted five years.

To weaken the resistance of Fez, in 1065 Ibn Tašufín pushed the regions to the east and north of the city, Magrawí regions that supported it. In 1066, he conquered the Rif, populated by Gumara groups. After new Unsuccessful assaults, he finally managed to seize Fez on March 18, 1070. He then undertook an intensive reformation of the city, which had been badly damaged by the fighting.

In 1071, the Almoravid armies conquered the region of the Muluya river and in 1073 they carried out a punitive campaign to the north, in the rebellious Gumara territories. In 1074-1075, they subjugated various Miknasa tribes between Fez and Taza. From 1075 to 1078, important groups of desert tribes settled in Morocco, called by Ibn Tašufín to consolidate Almoravid power in the region.

Next, the Almoravids decided to conquer the still independent redoubts around the Strait of Gibraltar; the governor of the region continually stirred up the Gumaras against the Almoravids. In 1077 they marched against Tangier, which they took after defeating their army at the gates of the city.

Once the Moroccan western Maghreb had been conquered, Ibn Tašufín implemented a territorial reform, creating a series of provinces and partially eliminating the tribal division that had characterized the territory until then. The different provinces were superimposed by the Marrakesh central government, initially with little income other than booty from conquest and gold from trans-Saharan trade.

Campaigns towards the central Maghreb

In 1079–1080, Ibn Tašufín sent a large army to eliminate the Magrawids from Tlemcen, who posed a danger to the eastern Almoravid territories. The army arrived near the city after disrupting the Cenete resistance, but he failed to take it. In 1081 Ibn Tašufín himself campaigned through the Rif and took Guercif, Melilla and Nekor, which he razed. He then conquered the region east of the Muluya, populated by the Banu Iznasan, and Oujda. he headed towards Tlemcen, which he managed to take.

The following year the expansion to the east continued, with the capture of Oran, Tenès and Algiers, a region also with a Cenete majority, like Tlemcen. which the Almoravids did not penetrate. At the end of the XI century, the Maghreb was dominated by three Berber groups: the Almoravids, the Hamadids and the Zirids.

The control of the western zone by Ibn Tašufín, forged in twenty years of campaigns, enhanced his prestige in al-Andalus, divided into taifas and threatened by the conquests and campaigns of the Christian states of the north of the Iberian Peninsula. In this there had been an inverse evolution to that which had occurred in the Maghreb: while it was unified territorially and religiously by the work of the Almoravids, in that of the territorial and religious unity of the Caliphate of Córdoba in the X turned to fragmentation and theological disputes. The Almoravid Maliki rigor contrasted with the religious and moral laxity of the north and earned the sympathy of the jurists, who saw the Berber group as a renovating and reactionary movement.

Factors that favored the Almoravid movement

The main factors that favored the Almoravid movement were:

- Tribal solidarity and religious reform.

- The economic factor. The vast tracts of land where the herds of the Sanhaya were pasture, presented a first-order interest: the control of the caravans loaded with all kinds of goods (mainly gold and salt) that were destined for North Africa and Al-Andalus. The Mesufa would control the Teghaza-Audagost-Siyilmasa axis; the Lemta the coastal itinerary from the mouth of the Senegal River to the Noul River region; the Gudala would control a salt mine in the southwest of the Atlantic coast; and the Lemtuna would control the Draa valley and the Audagost-Sus direction Siyilmasa axis.

- Fragmentation of the Muslim world. In Ifriqiya (now Tunisia), the Hilalian invasion, the fall of Kairouan (1053) takes place with attempts to thrive westward. In the Western Maghreb (now Morocco), the Barghawata dominate the Atlantic plains, the Idrisites retain the cities of Tamdoilit, Igli and Massa with the intention of taking Ceuta to the Omeyas of Cordoba; the Magrawa and their cousins, the Beni Ifren (Yafran), control Salé, Tlemecén, Tadla and Fezzaz; Al-Ándalus was broken into a multitude of Taifas kingdoms.

Disembarkation in the Iberian Peninsula

At the beginning of the 1080s, Ibn Tašufín began to receive requests for help from some Andalusian kinglets. to the union of Islam against Christian attacks and to the religious orthodoxy represented by the Almoravids. The first was Al-Mutawákkil of Badajoz, after Alfonso VI conquered Coria in 1079. In 1082, the king of the taifa Sevillian, Al-Mu'tamid, had refused to pay the pariahs promised to Alfonso VI of León and had ordered the assassination of his envoys. This triggered a retaliatory incursion the following year through the south of the peninsula, which frightened to the Muslim sovereigns of the region. That same summer, Al-Mu'támid, in agreement with Al-Mutawákkil of Badajoz, requested the help of Ibn Tašufín who, without rushing, began to consider the possibility of intervening in al-Andalus.

To begin with, he surrounded Ceuta, the only place that still escaped his control in the western Maghreb. The Almoravids had already conquered it in 1077, but they had lost it again. The emir counted to subdue the with the help of Al-Mu'tamid's fleet, which disrupted attempts to maintain supplies by sea. In September 1084, the city fell into the hands of the besieging army, which a son of Ibn Tašufín, Tamim al-Mu'izz, commanded. Ibn Tašufín then marched to Fez to begin the concentration of forces to cross over to the Iberian Peninsula.

While he was doing it, slowly, Alfonso VI (1040-1109) took Toledo on May 25, 1085 and in 1086 he marched to try to seize Zaragoza as well, which alarmed the Andalusians, who saw their future in danger, which prompted them to make the decision, not without great reservations, to call to their aid the seasoned Almoravid warriors, a faction that preached orthodox adherence to Islam. The loss of Toledo, especially, had reinforced supporters to request the help of the Almoravids. Tašufín in these terms:

He (Alfonso VI) has been asking us for pulpits, minaretes, mihrabs and mosques to lift crosses in them and to be governed by their monks [...] God has granted you a kingdom in prize to your Holy War and to the defense of His rights, for your work [...] and now you have many soldiers of God who, fighting, will win in life paradise.Cited by al-Tud, Banu Abbad, Ibn al-Jakib, al-Hulal, p. 29-30

The delegation of the three taifas agreed with Ibn Tasufín to carry out a campaign against the peninsular Christian states, in exchange for the ceding of Algeciras, which was to serve as an entry point to the territory of the Almoravid forces. The Andalusian sovereigns promised to join forces with the Almoravids against the Christians of the north and to pay for the campaign, and Ibn Tašufín, for his part, to respect their independence. In June the journey of forces began Almoravids to Algeciras, which they carefully reinforced and supplied, trusting little in the versatile Andalusian kinglets.

Almoravid conquest of al-Andalus

Stop the Castilian expansion

Despite the tension generated by the unexpected Almoravid landing, carried out earlier than agreed, and the subsequent siege of Algeciras that forced the immediate surrender of the city by the Sevillians, Ibn Tasufín managed to gather around him emirs of the southern taifas —Seville, Granada and Badajoz— to undertake the offensive against the Christians. Their hosts were well received in the region, eager to regain the initiative against the northern enemies.

Ibn Tasufín marched in September to meet with Al-Mu'tamid in Seville. A general appeal was then made to the Andalusian sovereigns to participate in the next campaign against the Christians, considered a war Santa. In October the Almoravid sovereign marched to Badajoz, accompanied by forces from almost all the southern taifas; The Christians had recently taken possession of Coria. At the same time, Alfonso VI had abandoned the siege of Zaragoza, passed through Toledo and advanced through Badajoz lands. Arrived near the capital of the taifa, agreed with Ibn Tasufín on the day of the battle, but he did not respect the agreement and suddenly attacked the Muslim forces. Although the Christians disrupted the enemy vanguard, made up of the taifa contingents, the second line, made up of Almoravids and Sevillians, stopped the attack and allowed the rearguard, under the command of Ibn Tasufín himself, to defeat them, although with notable losses. Thus, the Almoravids, determined and more numerous, defeated Alfonso in the battle of Sagrajas, the October 23, 1086. The Muslim victory allowed the kings of the taifas to stop paying pariahs to Alfonso.

They did not take advantage of the victory since, recently obtained, the emir Yusuf ibn Tasufin returned to North Africa because his son and heir, Abu Bakr, had just died. The Almoravid triumph had eliminated temporarily from the Christian harassment of the western taifas, but this persisted in the eastern ones, and Ibn Tasufín had barely left three thousand soldiers on the peninsula when he withdrew. He also granted the Almoravids the role of mediators between the unwelcome Andalusian sovereigns and their guardians, until their subsequent disappearance. For two years, however, relative calm reigned on the peninsula, while Ibn Tašufín strengthened his control of the Maghreb territory and the Christian forces regrouped. The Almoravid sovereign exhorted in vain the Andalusian rulers to observe more strictly the Islamic dictates and to unite against the enemies of the north and for the moment he avoided mixing in peninsular politics.

In Xarq al-Andalus, the Castilians threatened Murcia from Aledo and in Valencia the Cid led a large host, paid for by the tributes he received from the Muslim sovereigns of the southeast. Faced with this situation, notables of the The region and the Sevillian emir requested Ibn Tasufín to carry out a second campaign against the Christians. Probably in June 1088, an unsuccessful attack was carried out against Aledo, frustrated by dissensions among the Andalusians. After four months of unsuccessful siege, the announcement of the arrival of Alfonso to the rescue of the square and the hostility of the Murcians, whose sovereign, Ibn Rashiq, had been handed over by the Almoravids to their Sevillian rival for cooperating with the besieged, they caused the siege to be lifted. The Christians, however, decided to evacuate the square and set it on fire, since the siege had damaged it a lot. In November and after sending two detachments to Valencia, Ibn Tašufín returned to the Maghreb.

With redoubled the exactions and Christian meddling in the territory, the Andalusians demanded with increasing insistence the annexation of the territory to the Almoravid State, which they considered the only possible protector against the Christians. with Alfonso after the failure of Aledo and his decision to resume paying the tribute upset Ibn Tašufín, who decided to put an end to them. In the Almoravid's opinion, the Andalusian kinglets had demonstrated their inability and weakness. The Almoravids criticized the divisions of the regulos, the luxury of their courts, the impotence they showed to stop the Christian attacks, their indifference to religion and the illegality of their tax system. The elimination of the taifas that they carried out, put an end, however, to the Andalusian artistic and cultural heyday that had been reached in the XI century, a consequence of the rivalry between the courts of the emirs. The situation improved for jurists and religious, —firm supporters of the Almoravids— but it worsened for poets and writers, although Almoravid sovereigns and governors did not completely do without them.

Annexation of the western taifas

The Almoravids crossed the Strait of Gibraltar again in June 1090 and gradually took over the Taifa kingdoms. The emir's first move was, however, to attack Toledo, where he should have to arrive at the end of July. At the end of August, the Almoravid army had not been able to seize the strategic square and, given the imminent arrival of relief under the command of Alfonso VI of León and Sancho Ramírez de Aragón, decided to abandon the encirclement. The emir does not seem to have counted on the collaboration of the Andalusian taifas this time and, to ensure the rearguard against new campaigns against the Iberian Christians, he prepared to subdue them.

Ibn Tasufín, with opinions from the jurisconsults contrary to the performance of the Zirid emirs of Granada and Málaga, summoned them before him. On September 8, he seized the first, which his emir had to deliver before the lack of sympathy from the population, which prevented him from opposing the Almoravid sovereign. needed to resist. In October the Almoravid sovereign also took over Málaga, whose lord was the brother of the deposed King of Granada.

Then Ibn Tasufín returned to the Maghreb, leaving his cousin Sir ibn Abu Bakr in the Iberian Peninsula with the mandate to reduce the rest of the taifas of al-Andalus. For this he had the determined support from the clerical party, represented by the alfaquis, who en bloc condemned the Andalusian sovereigns, thus justifying their overthrow at the hands of the Almoravids, who appeared as just defenders of the faith. Five different armies attacked the various Andalusian monarchs.

The Almoravid leader conquered Tarifa before the end of that year, in December, with the aim of ensuring communications with the Maghreb. He then went against the important Taifa of Seville, which to defend itself joined forces with Alfonso VI. The alliance had two important consequences: that Zaida, the widow of al-Mutámid's son, was sent to Alfonso and had with him the heir from Leon, Sancho Alfónsez, and the transfer of a number of of important border fortresses that would serve the king of Leon to defend Toledo. Among these were: Alarcos, Caracuel, Consuegra, Cuenca, Huete, Mora, Oreja and Uclés. Most of the fortified towns surrendered without resisting. On March 27, 1091, the Almoravids took Córdoba, whose defense was led by one of the sons of the Sevillian emir, who perished in it. From there he seized the fortress of Calatrava. Another of the sons of the Emir of Seville ended up handing over Ronda in April. On 9 March ayo, the North Africans seized Carmona, after besieging Almodóvar del Río. The Castilians, who came to the aid of the Sevillians late, were defeated in Almodóvar del Río; in September, after several months of siege, Seville fell, which was sacked. At the same time, another Almoravid host took control of Almería, whose new emir abandoned it and went to take refuge in the court of the Hamadids of the Maghreb.

After taking Úbeda, the Berbers subsequently subdued the taifas of Jaén, Murcia —in October 1091— and Denia. At the end of 1091, of the southern taifas, only Badajoz remained independent of the Almoravids. The following year, a son of Yúsuf ibn Tasufín, Muhámmad ibn Aisha also expelled the Castilians from Aledo and advanced to Alcira. The capture of Aledo opened the way to Valencia, an Almoravid objective for the next decade. The advance from Ibn Aisha to this, in which he took possession of Denia, Játiva and Alcira (1092), he hardly found opposition. Given the proximity of the Almoravids and the absence of El Cid, a faction from Valencia rose up against his puppet lord Al-Cádir, assassinated him, and took over the government of the city, which he did not hand over to the Almoravids.

Although he had collaborated with the North Africans, Badajoz was annexed at the beginning of 1094. The emir had tried to avoid this by allying with Alfonso VI in exchange for ceding Lisbon, Cintra and Santarem, to no avail. Both he and his sons were killed when they were being taken captive to Seville. In November of that year, Ibn Abu Bakr seized Lisbon, which Count Raymond of Burgundy, husband of Princess Urraca, was unable to defend. By the end of 1094, all of al-Andalus, with the exception of the eastern area, dominated by El Cid, had passed into Almoravid hands. The government of the new provinces, which basically maintained the borders of the taifas disappeared, generally remained in the hands of relatives of Ibn Tasufin, often sons and grandsons.

Annexation of the eastern taifas

While the Cid was away on a ride through the lands of La Rioja, an uprising took place against the puppet sovereign of the taifa, Al-Qádir, ordered assassinated by the qadi Ibn Yahhaf; the insurgents handed over the town's citadel to the Almoravids. The Almoravids then continued their slow advance northward, along the coast, and also subdued the Taifa of Alpuente.

El Cid undertook the return to Valencia in November 1092 and conquered some strategic towns on the way to regain control of it. In principle, the Valencians agreed to resume paying tribute to the Castilian due to the passivity of the Almoravids, who avoided confronting him. The pact between the two sides, however, was temporary, and fell apart in July 1093. After a long siege that lasted from the autumn of 1093 to June 17, 1094, he finally recovered Valencia. The successive Almoravid attempts to rescue the city failed. In the autumn of 1093, the attempt to help the fenced off had failed, due to the flooding of the garden by El Cid; the next campaign came too late, after the city had been surrendered. In August or September 1094, new Almoravid forces crossed the strait to support the conquests in the Levant and retake Valencia, led by a nephew of Ibn Tasufin, Abu Abd Allah Muhammad. ibn Tasufín. El Cid twice repulsed the Almoravids, the first time when they came to reconquer Valencia in the autumn of that same year in the battle of Cuarte, in which he obtained victory through a ruse, and in a second attempt in January 1097, in which he defeated them in the battle of Bairén, with the help of reinforcements sent by Pedro I of Aragón. He protected the eastern taifas for some years, the only ones that had not yet the Almoravids had conquered. He dominated the region until his death in 1099, despite the hostility of his emirs, who collaborated in the Almoravid raids.

Ibn Tasufín crossed the strait again in mid-1097, concerned about the resistance of El Cid and the inability of his forces to take Valencia. Christians could concentrate in the east. In effect, it forced Alfonso VI to return to the center of the peninsula when he was already on his way to Zaragoza. The Leonese forces tried to defend the southern border of the kingdom, which at that time approximately followed the line Consuegra-Belmonte-Cuenca, and requested help from El Cid, who sent his son and Aragon. The clash between the two armies occurred in Consuegra on August 15 and ended with a clear Muslim victory. The fortresses that protected Toledo, however, remained in Christian hands with the exception of Consuegra itself, which the Almoravids seized in 1099. After the battle, the Almoravids had unsuccessfully surrounded it for several days, and had beaten to alva r Fáñez in the region of Cuenca. Despite having won, the Almoravids withdrew quickly.

The triumph, however, did not help them to take Valencia, where El Cid decided to remain instead of going to Toledo, fearful of new revolts or Almoravid coups if he was absent from the city. His nephew Álvar Fáñez However, he was also defeated in Cuenca during the summer by the forces commanded by one of the sons of Ibn Tasufín, Muhammad ibn Aisha. Subsequently, he defeated a Valencian contingent near Alcira.

The continuous Christian setbacks did not prevent the Cid from taking Murviedro and Almenara, but they served as a prelude to a new campaign that Ibn Tasufín prepared and which ended up breaking their resistance. In 1099, the Cid already dead, The Almoravids took Consuegra in June and a large part of the fortresses that protected the region, but they failed to take Toledo, which they attacked the following year. The conquest of Consuegra caused the Leonese to lose a large part of the Toledo taifa of the which they had seized in 1085 and set the border at the Tagus, which left Toledo highly exposed to future Almoravid assaults.

At the end of August 1101, new Almoravid hosts appeared before Valencia and subjected it to a siege. In May 1102, Jimena Díaz, widow of El Cid, evacuated the city, which she set on fire, helped by Alfonso VI, who came to direct the operation. The King of Leon had managed to disrupt the siege in April but, aware of the strength of the attackers and unable to defend it, he had decided to evacuate it. The Almoravids then took over of Valencia on May 5. Some places located further north, until then controlled by allies or protégés of the Cid, fell into his power: Castellón in 1103, Albarracín in April 1104. Alpuente, Lérida and Tortosa were also subjected, on unknown dates.

By then, only the great Taifa of Zaragoza and the island of Mallorca were escaping from the Cenhegíes.

Last actions of Ibn Tasufin

Emires almoravides

|

While the conquest of al-Andalus was completed, the Maghreb territories remained calm and prosperous, except for the region of Tlemcen, whose governors insisted on harassing the neighboring Hamadids. Although they conquered Assir at the end of 1102, they were defeated by the Hamadid emir and temporarily lost Tlemcen, which was sacked as punishment for the Almoravid incursion. At the beginning of 1103, Ibn Tasufin went to the Iberian Peninsula to inspect the government of the territory and have his son Ali ibn Yusuf recognized as heir. which had already been proclaimed such the previous year in the Maghreb. He then appointed the conqueror of Valencia as governor of the region of Tlemcen, to take care of straightening out the affairs of the problematic region.

That same year, Alfonso VI undertook the siege of Medinaceli, a strategic place on the road that connected Zaragoza with Seville. The people of Leon also defeated an Almoravid army in the surroundings of Talavera de la Reina in June, fighting in the that the governor of Granada perished.

In the Iberian Peninsula, the new governor of Valencia annexed the Taifa of Albarracín on April 6, 1104 and provided aid to the sovereign of Zaragoza, threatened by Alfonso I the Battler. These were the last notable acts of Ibn Tasufín, who returned to the Maghreb, where he died almost a hundred years old on September 4, 1106 in Marrakech. The subjugation of Zaragoza and the Balearic Islands remained for his son and heir, Ali. This, who was twenty-two years old, seized power without problems. Only a nephew rose against him, in Fez, and the rebellion was crushed before the end of the year. During the first years of his reign, the empire reached its maximum extent. After a decade of progress, however, its decline began, which Ali failed to stop.

The administration established by the late emir, very effective during his reign and whose core was the army, was headed by a group of relatives and close allies of the sovereign, with whom a series of Andalusian secretaries collaborated, incorporated during the Iberian conquest.

Zaragoza and the Balearic Islands

Zaragoza maintained a balanced position between its neighbors to the south and the increasingly threatening Christians to the north. The Aragonese had taken several plazas in the last years of the century XI and early XII (Monzón in 1089, Huesca in 1096, Barbastro in 1100, Ejea in 1105, etc.) and advanced towards the Ebro. Although he paid outcasts to the Christians and had employed El Cid, the emir from Zaragoza also tried to maintain good relations with the Almoravids. In 1102, Al-Musta'in II sent his son to Marrakech to participate in the proclamation as heir of Ali ben Yusef ben Tashfin, presenting his state as a barrier against Christian advance, with which he managed to postpone a campaign against him that was about to be launched from Valencia. From that year and with the capture of the latter, he had begun After the Almoravid expansion to the east of the taifa: Lérida, Fraga (1104) and the coast from Tortosa to Valencia fell into the hands of the Cenhegíes. Zaragoza stopped paying the pariahs to Alfonso VI. This taifa preserved its independence thanks to, in part, due to the good relations that Al-Musta'in II of Zaragoza maintained with the emir Yúsuf ibn Tasufín. From 1106, however, he was practically a vassal of the Almoravid emir.

Al-Musta'ín died when he returned from an incursion through the lands of Tudela in 1110 with which he had tried to appease the pro-Almoravid party and give a sense of firmness to the Christians, he was succeeded by his son Abdelmálik, who he failed to hold onto the throne. His own subjects requested that the Almoravid army that came to the city to seize it withdraw, but then they overthrew the new sovereign and handed over Zaragoza to the Almoravid governor of Valencia on 31 May 1110. Abdelmálik had by then withdrawn to the fortress of Rueda de Jalón, without sufficient forces to oppose the Almoravids.

Only that of Mallorca remained independent of all the Andalusian taifas, due to its island situation and the power of its fleet, with which it constantly plundered the coasts of the Christian States. Against it they sent Catalans, Genoese and Pisa an expedition in 1114. Ramon Berenguer III commanded the expedition that lasted almost the whole year, allied with the Republic of Pisa, the Viscount of Narbonne and the Count of Montpellier. The Christians landed in August 1114 and they took Majorca in April of the following year. After sacking it and carrying out a great slaughter, they withdrew. An Almoravid fleet arrived at the end of 1115 and took possession of the islands. The last of the almoravid taifas Andalus succumbed at the end of the year 1116.

The easy conquest of the region by a group considered barbaric by the aborigines was due both to the extreme military weakness of the taifas (which lacked -except Seville- appreciable forces, generally depended on few mercenaries and, for the payment outcasts, they did not have the funds to hire larger contingents), as well as the favor that part of the population, especially the alfaquíes, granted the Almoravids. The lawyers appreciated the element of religious renewal of the movement, its inclination to holy war, as well as the opportunity to gain political and religious influence, given the notable respect with which its leaders treated the opinions of religious experts on these two aspects. It was this group, that of the alfaquíes, that granted the main legitimizing support for the Almoravid expansion and its tax system. The merchants and the common people appreciated the possibilities of trading with the Maghrebi provinces of the invaders. s and the promise to abolish taxes not stipulated in the Koran —necessary for the payment of pariahs and for the maintenance of mercenary troops and onerous courts—, which in many cases deprived the petty kings of the taifas of all support and the possibility of preventing the loss of their territories.

Victories of Ibn Yúsuf in western al-Andalus

The Almoravid military chiefs maintained a constant harassment against the enemies of the north, who found themselves in an unequal situation to face it. The County of Portugal and Castile were weakened and vulnerable to the Almoravid assaults, while the kingdom of Aragon —protected during the first years of the reign of Ali ibn Yusuf by the Zaragoza taifa— and the county of Barcelona were in a much better military situation to repel them.

The military campaigns were left in the hands of Ali's brother, Tamin, whom he had appointed Governor General of al-Andalus. He gathered forces from various parts of the peninsula in early May and marched against the key fortress of the Castilian defensive system in the Tagus, Uclés. The Almoravids took the fortress by surprise on May 27, whose citadel resisted. A few days later a Castilian army came to the rescue of the square, in which were Sancho Alfónsez, the heir of Alfonso VI of Castile, and two of his best captains: Álvar Fáñez and García Ordóñez. The battle of Uclés, very hard fought, ended with a Christian defeat and, above all, everything, with the death of the Infante de León. Although at the beginning the Castilians had managed to push back the Almoravid center, they were flanked and were defeated. Fáñez managed to escape from the enemy encirclement, but Sancho and the seven counts who accompanied him perished when they fled to take refuge in the castle of Belinchón; the Muslim population of this town rose up against the Leonese and put them to arms. The Castilian defeat was a military disaster: the fortified border of the Tagus was dismantled, in which a series of squares were lost (Medinaceli, Huete, Ocaña and Cuenca). Almost the entire border region —mainly the Tagus valley— passed into the hands of the Almoravids. These gains allowed them to take over the old Roman road that connected Seville with Zaragoza, which they managed to seize shortly after, in 1110. They also tighten the siege of Toledo by hindering its communications with the outside world.

The following year, in August 1109, the Almoravid emir tried to take advantage of the Castilian weakness to take Toledo. He already dominated the fortresses to the east of the city, which he had conquered after the victory at Uclés, and decided to seize the main western one, Talavera. His forces took it by assault on the 14th of the month, after partially emptying the moat that protected it. After running through the lands of Guadalajara and Madrid, they established the siege of Toledo, defended by Álvar Fáñez, whom the Almoravids had already defeated on previous occasions. This time, however, he successfully defended the square and tenaciously repelled the enemy assaults; after a month of operations and without progress, Ali ordered the lifting of the siege and returned to Córdoba. During Urraca's turbulent reign, the defense of Toledo remained essentially in the hands of Fáñez —until his death in Segovia in 1114— and the city's bishop, of French origin, Bernardo. Although the Almoravids es had failed in the objective of the campaign, they maintained the military initiative in the region, while Castile, which had suffered harsh punishment for the enemy raids, plunged into succession problems, since the elderly Alfonso VI had died on June 30. In the following years they seized important squares of the old taifa, which they devastated: Oreja (1113), Zorita, Albalate and Coria. Toledo, on the contrary, continued to resist them: the Almoravid governor tried in in vain to take it in 1114 and 1115, and he perished defeated trying to seize it this last year. Despite the Almoravid siege, the Leonese held on, undertook some counterattacks and kept a series of strategic places that served to defend Toledo: Madrid to the south of the Central System and Ávila, Segovia and Salamanca, to the north of this.

Sir ibn Abu Bakr carried out an offensive through the westernmost regions at the end of the spring of 1111: he recovered Badajoz, which had risen in revolt, and Lisbon and took Cintra, Évora and Santarém. The latter had been one of the main Christian strongholds in the region, from which Lisbon and its surroundings had been threatened.

At the other end of the peninsula, al-Hach continued to harass the Aragonese and Barcelonans from Zaragoza. In 1112 he carried out an algazúa through the region of Huesca. The following year, between June and September and helped by Lleida forces, ran the county of Barcelona, taking advantage of the absence of his lord, who was in the Balearic Islands. Although the bulk of the army, loaded with rich booty, managed to return without setbacks, al-Hach, who decided to shorten the way Because of steep terrain, he fell into a trap in which he lost his life along with most of his companions, near Martorell. This defeat had an important consequence: the loss of the military leadership of the Levante forces, both for the death of al-Hach and for the incapacitation into which Ibn Aisa fell, shocked by the massacre from which he managed to escape with great difficulty.

At the end of 1114 or the beginning of the following year, Ali's brother-in-law and then Governor of Murcia, Abu Bakr ibn Ibrahim ibn Tifilwit, took command of the Levantine forces, who undertook a punitive raid along the coast which reached Barcelona. At the end of April or the beginning of May, Ramón Berenguer, having returned from Mallorca, lifted the siege of his capital and forced the Almoravids to withdraw. During the following two years, the Valí de Zaragoza did not undertake new campaigns.

In May 1117, Ali himself crossed over to the peninsula, and led a large host westward. After passing Santarém, he entered Christian territory and in June besieged and conquered Coimbra, which he abandoned, however, after a few weeks. In 1119, the Almoravids took over Coria, conquered by the Leonese in 1079.

Decay

As soon as it reached its territorial apogee around 1117, the Almoravid Empire immediately began its decline. Its rise and fall were so rapid that the Cenhegis dominated al-Andalus for only a generation. In the Iberian Peninsula and despite Due to the very serious crisis in which Castile was plunged upon the death of Alfonso VI, the rest of the States began to harass the Almoravids vigorously. Alfonso I of Aragon was especially active, who first seized Zaragoza in 1118, after the fortresses in the south of the vega del Ebro (Calatayud and Daroca) and continued to attack the Almoravid forces until his death in 1134. In the first half of the century, he completely dismantled the Andalusian Upper Frontier, which seriously damaged the Almoravid military prestige. In the west, Castilian weakness allowed the county's independence from Portugal, first in the hands of an illegitimate daughter of Alfonso VI and then his son, Alfonso, who assumed the title of r ey and expanded his domain at the expense of the Almoravids with the help of crusaders from northern Europe.

Defeats in the Ebro and Andalusian discontent

Taking advantage of the confusion in Zaragoza due to the death of the vali in 1116-1117, Alfonso I resumed the attacks against the city and its region, which he kept in constant anxiety. In 1117, before the arrival of a new governor, he had to retreat, but he ran over the lands of Lleida, threatening the city itself. Various Almoravid hosts gathered to force the Aragonese to abandon their attempt to take it.

Alfonso, however, did not give up his harassment of the Almoravid forces in the region: with the support of Frankish knights, he undertook the siege of Zaragoza on May 22, 1118. which, together with the hunger caused by the siege and discouragement, led to a truce being agreed, during which the besieged asked Valencia for help. The forces that reached the city, fewer in number than the Aragonese, did not dare to engage in battle and allowed the square to fall into their hands on December 18. The determined Almoravid efforts to preserve the city had failed. The military initiative in the region passed to the Christians: a few months after conquering Zaragoza, in February 1119, Alfonso also took over Tudela. Shortly after he took control of various places in the plain south of the Ebro: Tarazona, Moncayo, Borja and Épila. He then advanced along del Jalón and threatened Calatayud, on the main road to Andalusia; The constant advance forced the wall of Murcia and the Levant, Ibrahim ibn Tayast, Ali's brother, to march north to try to stop him. The operation was a disaster for the Almoravids, who suffered a terrible defeat at the Battle of Cutanda, fought in June or July 1120 between this town and Calamocha. As a result of the battle, they lost the Jalón Valley, including Calatayud, which passed into the hands of Alfonso in 1121. In 1122 he took Daroca, which confirmed the continuous Almoravid retreat in the area.

The defeats in the Ebro were compounded by growing discontent on the part of the Andalusian population, fed up with Almoravid rule. The effervescence increased in 1120 and 1121, and in March of the latter year a revolt broke out in Córdoba that he forced the governor of the city to flee from the angry crowd. Ali reacted by gathering a large army and going from Marrakech to the Andalusian city, which he first attacked and later pardoned, convinced by the local alfaquis.

Although at the beginning the Almoravids had been able to sustain their State while abolishing non-canonical taxes by not having to pay the onerous pariahs to the Christians, by having volunteer troops at a lower cost than the mercenaries of the taifas, Due to the frugality of the Berber soldiers in the desert, due to the booty obtained from the victories - a fifth corresponded to the sovereign, according to the law - and due to the income due to gold from the trans-Saharan trade, over time the financial situation worsened, the expenses of maintaining a defensive and continuous war increased, and the imposition of taxes not included in the Koran was recovered, with the consequent disgust of the population. The recovery of heterodox tributes and the use of Christian mercenaries in the Maghreb it scandalized the most pious, who had initially acclaimed the Almoravids for their Islamist rigor.

Reversals and victories in the Iberian Peninsula

The discontent of the Mozarabs grew to the point that in 1124 they called on Alfonso I of Aragón, who had just won an important victory over the Almoravids, taking the great city of Zaragoza in 1118. Earlier that same year, the Leonese had seized Sigüenza and also dominated nearby Atienza and Medinaceli. The Granada Christian community promised the Battler to rebel against the governors of the capital and open the gates of the city for him to conquer.. Thus, the Aragonese king undertook a military incursion into Andalusia in September 1125 which, although it did not lead him to conquer Granada, did reveal the military weakness of the Almoravids for those dates, since he defeated them in the open field in battle from Arnisol, plundered the fertile Andalusian countryside from Granada to Córdoba and Málaga at will, and rescued a large contingent of Mozarabs to repopulate the recently conquered lands of the Ebro Valley with them. This campaign, which lasted almost a year until June 1126, it showed the decline of the Almoravid Empire, unable to stop the incursion of the Aragonese monarch.) deported to North Africa.

Alfonso seized new places in 1127 and 1128: the first year of Azaila, the second, of Castilnuevo and Molina de Aragón. In 1129, he felled the Valencian region and defeated a large army near Alcira or Cullera. The Almoravids reacted to the Aragonese campaigns by carrying out a series of administrative replacements of the main offices in al-Andalus and launching an offensive towards Toledo in 1130 which, although it managed to conquer Aceca, failed to try to recover the city of the Tagus. From then on, Tasufín, son of Ali, remained Governor General of al-Andalus until 1138. During his rule, the Almoravids managed to maintain a certain balance in the military situation.

The accession to the Castilian throne of Alfonso VII marked the beginning of another period of strengthening of Castilla y León, and of danger for the Almoravids. The Castilians were allied with the son of the last Zaragoza emir, who handed over Rueda de Jalón Alfonso in exchange for a few castles on the Toledo border, eager to avenge his father's defeat at the hands of the Almoravids by confronting them. In May 1133, the Castilians carried out a raid on Seville, in which they gave death to the governor of the city and felled the region before withdrawing. The Almoravids did manage, however, to frustrate a similar expedition through the lands of Badajoz organized by the magnates of Salamanca in March or April 1134., hindered Christian attempts to fortify the region of Cáceres. In 1136-1137, Tasufín defeated the Castilians at Alcázar de San Juan and sacked the castle of Escalona.

In the east, Alfonso the Battler continued to harass the Almoravid populations. In 1130, however, he lost his ally Gastón IV of Bearne, who fell in a raid through Valencia. He took possession of Mequinenza (1133) with help from a fluvial squadron built in Zaragoza and, subsequently, surrounded Fraga in June or July 1134. The Andalusian governor-general, Tasufín ibn Ali, sent abundant reinforcements, which defeated Afonso in the hard-fought battle of Fraga. The Almoravid victory was not used, however, to squeeze the Aragonese - who died in September of injuries suffered -; the Almoravid attacks continued to focus on recovering Toledo, an objective that they did not reach. They did recover, in any case, Mequinenza, in 1136, which allowed them to improve the border situation in the lower Ebro.

The envy of the heir to the Almoravid throne, Sir, for the prestige of his brother Tasufín due to his victories in the Iberian Peninsula prompted him to request his replacement, which he obtained. After Tasufín left for the Maghreb, the situation on the peninsula it quickly worsened for the Almoravids. In the Maghreb, Tasufín immediately took the reins of the fighting against the Almohads.

Andalusi influences and internal crisis

After reaching its maximum expansion, the Almoravid Empire received the influence of the Andalusian culture, whose artistic creations it assimilated. The western Maghreb lacked its own artistic model, it was a mostly rural society with few urban centers and its modest art it was distantly influenced by that of the East. Thus, the Almoravid and Almohad Berber dynasties adopted the Andalusian style for their artistic works, since they lacked their own in their regions of origin. More than in the structure of the buildings, the Andalusian influence in the art of the Almoravid period is observed in the decoration of these. The traditional ataurique is complicated and increases in density, completely covering the wall where it is placed. The baroque character of this ornamentation, which can be seen before in the furniture that in the buildings, has its precedent in some works of the Andalusian taifas, and is accentuated during the reign of Ali. The new capital, Marrakech, foundation From this movement, it began to embellish itself in the emirate of Ali, collecting the forms of the art culture of the taifas. Few examples of Almoravid art remain (and only of military architecture in the Iberian Peninsula), such as the Qubbat al-Barudiyin in Marrakech.

The Almoravids also assimilated written culture: mathematicians, philosophers and poets took refuge in the protection of the governors. The secretaries who came from the peninsula also influenced the management of the Public Administration, since it actually depended on them. The customs were relaxing, despite the fact that, as a general rule, the Almoravids imposed an observation of the precepts religions of Islam much more rigorous than what was customary in the first taifa kingdoms. The mystic al-Ghazali was banned, but there were exceptions and in the Zaragoza of Ibn Tifilwit the heterodox thinker Avempace came to occupy the position of vizier between 1115 and 1117. Following Islamic law, the Almoravids suppressed the illegal payments of pariahs, not contemplated in the Koran, at the beginning of their empire. They unified the currency, generalizing the gold dinar of 4.20 grams as a reference currency and creating fractional currency, which was scarce in al-Andalus. The Almoravid dinars enjoyed notable prestige in the region's markets and came to be used as the reference monetary unit in Western Europe. They stimulated trade and reformed the administration, granting broad powers to the austere religious authorities, who promulgated various fatwas, some of which seriously harmed Jews and, above all, Mozarabs, who were persecuted during this period and pressured to convert to Islam. It is known that the important Jewish community of Lucena had to spend significant amounts of money to avoid their forced conversion.

Around those same years, the Almohads began to harass the Almoravids in the heart of the western Maghreb. They fueled discontent due to the relaxation of customs, the influence of the conquered Andalusian culture. In 1121, after a theological dispute held in Marrakech that was unfavorable for the Almoravid alfaquíes, defeated by the knowledge and skill of the founder of the Almohad movement, Ibn Tumart, the authorities deported him. He then settled in the Atlas Mountains, where he was from and where he formed a community with his followers, which became the seed of a new State that ended up eliminating the Almoravids. The Almohads, who arose from the Masmudid tribes of the Atlas, had in their beginnings notable similarities with their Almoravid enemies: they had a clear tribal origin —Masmudid in the Almohad case, Cenhegi in the Almoravid—, a reactionary religious spur —they both advocated a return to Islamic values and customs they admired—and were a movement that was at once tribal, political, and religious.

End of the Almoravid empire: the Almohad triumph

Unsuccessful struggle against the Almohads and loss of the Maghreb

Due to the extension of Ibn Tumart's movement, which the Almoravids began to fear, an assassination attempt on the religious leader was hatched, which failed. A military campaign against the tribes that were loyal to him, led by the Almoravid governor del Sus in 1122 or 1123, also failed. The Berber empire of Saharan origin, created by the Cenhegi Almoravids, was opposed by a growing State, also Berber, but of mountainous and Masmudid origin, centered on Tinmel, where Ibn Tumart had settled. As the Almoravids themselves had done at the beginning of their expansion, the Almohad rebels clamored for the reform of customs, the carrying out of holy war and purification.

Around 1125 a new power was emerging in the Maghreb, that of the Almohads, which emerged from the Masmuda tribe, which they achieved with a new spirit of rigorous application of Islamic law, since the customs of the Almoravids had been largely relaxed. measure due to contact with the advanced Andalusian culture, finally prevailing over the Almoravid power after the fall of their capital Marrakech in 1147. To try to oppose their expansion and already unsuccessful campaigns in the mountains, the Almoravids chose to erect a chain of fortresses around the mountain range to encircle Ibn Tumart's movement and protect themselves from his incursions. At the same time, the Almoravid regional authorities harassed the Almohads, generally with little success in the various clashes. Until 1129, the fighting they fought in the mountains, the Almohads still not daring to face the enemy on the plain.

The Almohads inflicted two major defeats on Ali's forces between Marrakech and the mountain in early 1130, which allowed them to approach the Almoravid capital. The two sides engaged in combat around the city, which withstood an Almohad siege forty days while reinforcements for the besieged arrived from different regions. In May the fenced finally decided to leave the city and attack the Almohads in the plain of al-Buhayra, where they had set up their camp. A very violent clash ended the Almoravid victory. This triumph temporarily ended the Almohad danger; a few months later the founder of the movement died in Tinmel, in August or September. Fighting with the Almohads continued in the mountains, and the territories they controlled isolated the southern provinces of the Almoravid capital. The fortress of Tasgimut in the summer of 1132 was a significant setback, both in terms of prestige —it caused some tribes to go over to the Almohad ranks— and strategically, since the conquest of the square gave its new lords access to the central and northern Atlas.

Since 1132, a new mercenary force, led by the former Viscount of Barcelona Reverter, played a fundamental role in the Almoravid defensive operations against the Almohads. From 1139 the fight against the Almohads remained in the hands of the new heir to the throne, Tasufin ben Ali ben Yusef, who had stood out in the fight against the Christians of the Iberian Peninsula and had succeeded his brother Sir, who died the previous year. Ben's march from al-Andalus Ali weakened the Almoravid position on the peninsula. At that time, in addition, the Almoravids lost control of the upper Sus.