Alaric I

Flavius Alaric I (in Gothic *𐌰𐌻𐌰𐍂𐌴𐌹𐌺𐍃, Alareiks: 'king of all'; in Latin: Flavius Alaricus; Peuce, 370/75 -Cosenza, 410) was a Visigothic military leader of the Tervingian tribe. He is considered the first historical king of the Visigoths, son (or paternal grandson) of the Visigothic leader Rocestes and brother (or nephew) of Afarid, he is part of the so-called Baltinga dynasty.

Reigned between 395 and 410, he is best known for his sack of Rome in 410, which was a decisive event in the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Alaric began his career under the Gothic general Gainas, and later joined the Roman army. He is first mentioned as the leader of a mixed band of Goths and allied peoples, which invaded Thrace in 391, only to be stopped by the general Stilicho. In 394, he led a Gothic force of 20,000 men that aided Emperor Theodosius I in defeating the usurper Eugenius and his commander, the magister militum Frank Arbogastes, at the Battle of Frigidus. Despite this, Alaric received little recognition from the emperor. Disappointed, he left the army, was elected king of the Visigoths in 395, and marched on Constantinople until he was driven away by imperial forces. He then moved south to Greece, where he sacked Piraeus (the port of Athens) and destroyed Corinth, Megara, Argos, and Sparta. Despite everything, the Emperor of the East Arcadius appointed Alaric magister militum , the highest military rank, in Illyria, which shows that he was a Roman citizen, since only a Roman could hold that rank. range.

In 401 Alaric invaded Italy, but was defeated by Stilicho at Pollentia (modern Pollenza) on April 6, 402. A second invasion that same year also ended in defeat at the Battle of Verona, although it forced the Roman Senate to pay him a great subsidy to the Visigoths. During Radagaiso's invasion of Italy in 406, he remained inactive in Illyria. In 408, the Western Emperor Honorius ordered the execution of Stilicho and his family, in response to rumors that the general had struck a deal with Alaric. Honorius then incited the Roman population to massacre tens of thousands of wives and children of foederati Goths serving in the Roman army. The Gothic soldiers then went over to Alaric, increasing the size of his force to around 30,000 men, and joined his march on Rome to avenge their murdered families.

Moving rapidly along Roman roads, Alaric sacked the cities of Aquileia and Cremona and plundered the lands along the Adriatic coast. The Visigothic leader then laid siege to Rome in 408, but eventually the Senate gave him a substantial ransom. In addition, he forced the Senate to free all 40,000 Gothic slaves in Rome. Honorius, however, refused to appoint Alaric as commander of the Western Roman army, and in 409 the Visigoths again surrounded Rome. Alaric lifted the blockade after proclaiming Attalus Emperor of the West. Attalus appointed him magister utriusque militiae ("generalissimo"), but refused to allow him to send an army to Africa. Negotiations with Honorius broke down, after which Alaric deposed Attalus in the summer of 410 and besieged Rome for the third time. The allies inside the capital opened the gates to him on August 24, and for three days his troops sacked the city. Although the Visigoths engaged in looting for Rome, they treated its inhabitants humanely and burned only a few buildings. Having abandoned a plan to occupy Sicily and North Africa after the destruction of his fleet in a storm, Alaric was killed as the Visigoths advanced north.

Early Years

Born on the island of Peuce at the mouth of the Danube delta in what is now Romania, the date of his birth is disputed, with scholars giving probable dates of 365/370 and 375. He belonged to the dynasty Baltinga of the Terving Goths. The Goths suffered setbacks against the Huns, so they made a massive emigration across the Danube, and made war against Rome. Alaric was probably a child during this period.

Serving the Romans

His childhood was spent within the Roman Empire, as his people had made a pact with Emperor Theodosius I and had settled as foederati in Moesia since the year 382, after the events that led to the the insurrection of the Goths and the defeat and death of the Eastern Emperor, Valens, in the battle of Adrianople in 378. During the IV, the Roman emperors habitually used foederati: irregular troops under Roman command, but organized by tribal structures. To avoid excessive taxes on provincial towns and to save money, the emperors began to employ units recruited from Germanic tribes. The largest of these contingents was that of the Goths, who in 382 (376 in some sources) had been allowed to settle within the imperial borders, maintaining a large degree of autonomy.

He led a Visigothic army allied with the Romans (387–395). In 394 Alaric served as a leader of the foederati under Theodosius I to defeat the usurper Eugenius. As the Battle of the Frigid, which capped this campaign, was fought at the passes of the Julian Alps, Alaric probably knew of the weakness of Italy's natural defenses on its northeastern border at the head of the Adriatic Sea.

Theodosius died in 395, leaving the empire divided between his two sons Arcadius and Honorius, the former assuming the eastern portion of the empire and the latter the western portion. Arcadius showed little interest in ruling, leaving most of the power behind. true in his praetorian prefect Rufinus. Honorius was still younger; as guardian, Theodosius had appointed the magister militum Stilicho. Stilicho also claimed to be Arcadius' guardian, causing great rivalry between the western and eastern courts.

According to Edward Gibbon in his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, during the changes in office that took place at the beginning of the new reigns, Alaric apparently expected to be promoted from mere commander to rank of general in one of the regular armies. However, he was denied this promotion. Among the Visigoths settled in Lower Mesia (now part of Bulgaria and Romania), the situation was ripe for rebellion. They had suffered disproportionately heavy losses on Frigid. According to a rumor, exposing the Visigoths in battle was a very convenient way to weaken the Gothic tribes.

This, combined with their post-battle rewards, prompted them to raise Alaric "upon the shield" and proclaim him king; according to Jordanes, a V century Roman bureaucrat of Gothic origin who later went down in history, both the new king and his people decided "rather to seek new kingdoms for themselves, than to slumber in peaceful submission to the rule of others". It seems that Theodosius I's heirs were unaware. According to the chronicles of Saint Isidore, «The Goths, refusing the patronage of the Roman foedus, constituted Alaric in assembly as their king, judging that he was unworthy to be subject to the power of Rome, whose laws and company they would have separated victors in battle." King Flavio Alaric was crucial in the process of decomposition of the Western Roman Empire.

In Greece

Alaric struck the eastern empire first. He marched through the vicinity of Constantinople but, finding himself unable to lay siege to it, he retraced his steps to the west and then marched south through Thessaly and the unguarded pass of Thermopylae into Greece. The armies of the eastern empire were busy with Hunnic raids on Asia Minor and Syria. Instead, Rufinus attempted to negotiate with Alaric in person, but only succeeded in arousing suspicion in Constantinople that Rufinus was in cahoots with the Goths. Stilicho then marched east against Alaric. Attacked by Stilicho, Alaric was forced to retreat. According to Claudian, Stilicho was in a position to destroy the Goths when Arcadius ordered him, through Rufinus's influence, to leave Illyria. Stilicho had problems with Arcadio and with the growing influence of his favorite Rufino of him. Soon after, Rufino's own soldiers hacked Rufino to death. Power in Constantinople then passed to the eunuch chamberlain Eutropius.

The death of Rufinus and the departure of Stilicho allowed Alaric freedom of movement; he sacked Attica in 396 (among his sacks is the abandoned sanctuary where the Eleusinian mysteries were performed) but spared Athens, which quickly capitulated to the conqueror. He then penetrated the Peloponnese and captured its most famous cities—Corinth, Argos, and Sparta—selling many of its inhabitants into slavery.

Here, however, his victorious career suffered a serious setback. In 397 Stilicho crossed the sea to Greece and succeeded in trapping the Goths in the mountains of Pholoi, on the borders of Elis and Arcadia on the peninsula. From there Alaric escaped with difficulty, and not without some suspicion of collusion with Stilicho, who supposedly had again been ordered to leave.

Alaric then crossed the Gulf of Corinth and continued his plunder from Greece north to Epirus. Here he continued his violent conduct until the eastern government appointed him magister militum per Illyricum, giving him the Roman command he desired, as well as the authority to resupply his men from the Imperial arsenals. The young emperor Arcadio would find a solution by agreeing with the Visigoths, and managed to settle Alaric and his people in Illyria, an area that at that time belonged to the eastern empire, but which was in dispute with the western part due to its proximity to Italy. With this, he managed to transfer the Visigothic problem from the eastern part of the empire to the western one, by removing the dangerous Alaric from Constantinople, which enervated Stilicho, who ended up ignoring any eastern or Arcadian problem.

First invasion of Italy

In the year 400, emboldened and discontented with his new lands, perhaps greedy for power, Alaric marched on Italy. It was probably in 401 that Alaric first invaded Italy, originally with the intention of asking for a position closer to Rome. Alaric had a fascination with the "golden age" of Rome and insisted that his co-religionists call him Flavius Alaricus. According to the Roman poet Claudian, he said that he heard a voice from a sacred grove, “Break all delays, Alaric. This same year you will force the alpine barrier of Italy; you will enter the city.” But that supposed prophecy was not fulfilled then. He spread desolation throughout northern Italy and terrorizing the citizens of Rome. He was stopped by Stilicho, who defeated him on April 6, 402 (coinciding with Easter) in the final battle of Pollentia, today in Piedmont. It was a costly victory for Rome, but it effectively stopped the progress of the Goths. They forced him to withdraw from Italy.

The enemies of Stilicho later reproached him for having obtained his victory by taking impious advantage of the great Christian festival. Alaric was an Arian Christian (unlike Stilicho who was orthodox), though he continued to practice the pagan rituals of his ancestors as well as observe Christian ritual practices. He had trusted in the sanctity of the Passover to make him immune to attack.

Alaric's wife was supposedly taken prisoner after this battle; it is not unreasonable to suppose that he and his troops were hampered by the presence of large numbers of women and children, which gave their invasion of Italy the character of a human migration.

After another defeat by Verona, Alaric left Italy, probably in 403. He had not "penetrated the city" but his invasion of Italy produced important results. He moved the imperial residence from Milan to Ravenna, and made it necessary for the Legio XX Valeria Victrix to withdraw from Britain.

Second invasion of Italy

It is probable that Alaric and Stilicho negotiated a truce or alliance to deal with the problems that were destroying the western part of the Empire: Vandals and Goths in northern Italy, insurrection of the troops of Britannia and military pronouncements that were they proclaimed Caesars, and, furthermore, Suevi, Vandals, and Alans crossing the Rhine in 406. Alaric had become a friend and ally of his erstwhile opponent, Stilicho. By the year 407, the rift between the eastern and western courts had grown so bitter that it threatened civil war. Stilicho proposed using Alaric's troops to reinforce Honorius's claim to the prefecture of Illyria. Arcadius's death in May 408 caused a softer stance to prevail at the western court, but Alaric, who had already entered Epirus, demanded in a somewhat threatening manner that if he were suddenly required to desist from the war, then they must pay well for what in modern parlance would be called "mobilization costs." The sum he pointed out was quite high, 4,000 pounds of gold. Under strong pressure from Stilicho, the Roman Senate agreed to pay it.

But three months later, Stilicho and the chief ministers of his party were treacherously assassinated on the orders of Honorius. In the ensuing insecurity throughout Italy, the wives and children of the foederati were slain. Consequently, the Goths went over to Alaric and flocked to his camp, increasing the size of the foederati. He brought his force down to around 30,000 men, and joined in his march on Rome to avenge their murdered families. He then led them across the Julian Alps and, in September 408, found himself in front of the walls of Rome, with no capable general like Stilicho to defend it, and a strict blockade began.

This time no blood was spilled; Alaric relied on hunger as his strongest weapon. When ambassadors from the Senate, suing for peace, tried to intimidate him with what desperate citizens might do, he laughed and gave his famous reply: "The thicker the hay, the easier it cuts!" After much bargaining, the starving citizens agreed to pay a ransom of 5,000 pounds of gold, 30,000 pounds of silver, 4,000 silken robes, 3,000 scarlet-dyed hides, and 3,000 pounds of pepper. Thus ended the first Alaric's siege of Rome. The combined value of the gold and silver in pure coinage would have been worth 7,000 pounds in gold or 1,028 million solids—enough to meet the basic needs of 200,000 adults and children for a year, or equip to 30,000 Roman infantry and cavalry.

Second Siege of Rome

Alaric's Visigoths, taking advantage of the weak situation of the Western Empire, forced Emperor Honorius to take refuge in the impregnable city of Ravenna and marched again on Italy. They tried to reach an agreement with Honorius. Throughout his career, Alaric's main goal was not to undermine the Empire, but to secure for himself a regular and recognized position within the Empire's borders. His demands were certainly great: the concession of a piece of territory 200 miles long by 150 miles wide between the Danube and the Gulf of Venice (to hold them in certain terms of nominal dependence on the Empire) and the title of commander-in-chief of the Imperial Army. As exorbitant as his terms were, he would have received better advice had he been told to give it to him. Honorius, however, refused to see beyond his own safety, guaranteed by Ravenna's dykes and marshes. All attempts to reach a satisfactory negotiation with the emperor failed and so Alaric, after a second siege and blockade of Rome in 409, reached an agreement with the Senate. With his consent, he established a rival emperor, the prefect of the city, a Greek named Priscus Attalus.

Third Siege of Rome

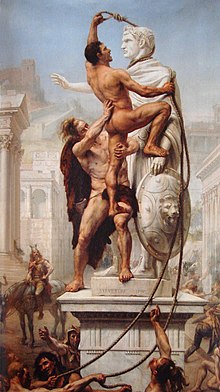

Alaric removed his ineffective puppet emperor after eleven months and reopened negotiations with Honorius. These negotiations might have been successful had it not been for the influence of another Goth, Saro, an Amelungo, and therefore a secular enemy of Alaric and his followers. Alaric, again outmatched by the machinations of the enemy, marched south and began his third siege of Rome. Apparently, the defense was impossible; there were suspicions, not entirely accredited, of treason; surprise is the most plausible explanation. Be that as it may, since our information at this point in history is scarce, on August 24, 410 Alaric and his Visigoths broke through the Porta Salaria in the northeast of the city. Rome, so long victorious against her enemies, was now at the mercy of her foreign conquerors.

Contemporary churchmen marvelously documented many instances of Visigothic clemency: Christian churches saved from ravages; protection granted to vast multitudes of both pagans and Christians who took refuge there; gold and silver tableware found in a private residence, which was liberated because it "belonged to Saint Peter"; at least one case in which a beautiful Roman matron appealed, not in vain, to the best feelings of the Gothic soldier who tried to dishonor her. But even these exceptional cases show that Rome was not entirely spared from the horrors that usually accompany entering a besieged city. In spite of everything, the written sources do not mention damage by the fire, except for the gardens of Sallustio, which were located near the door through which the Goths made their entrance; nor is there any reason to impute extensive destruction of the city's buildings to Alaric and his followers. The Basilica Aemilia, in the Roman Forum, burned down, which may perhaps be attributed to Alaric: the archaeological evidence of coins dating from 410 that They were found melted on the ground. The tomb of the pagan emperors of the Mausoleum of Augustus and Castel Sant'Angelo were searched and the ashes scattered.[citation needed]

Alaric demanded that Emperor Honorius be named magister militum or general of the armies of the Empire, since as a full-fledged Roman he could claim said honor, but that claim would never be fulfilled. However, from Rome he took as booty the emperor's half-sister, Princess Galla Placidia.

Since I took Rome into my hands, no one has ever despised the power of the gods. What prompted the desire for conquests and the desire for adventure gave greatness to a people in need of homeland.Flavio Alarico I, king of the Visigoths

That first looting of classical Rome shocked the civilized world of that time, as can be seen, for example, from the work of Saint Augustine, bishop of the city of Hippo.

Death and funeral

Alaric, having entered the city, then marched south to Calabria. Alaric began to dream of North Africa which, thanks to his grain, had become the key to holding Italy. He left for La Reggiana with the intention of embarking for the "granary of Rome." But a storm destroyed his ships and many of his soldiers drowned. The truth is that the Visigoths were a brave and hardened people, but they did not exactly stand out for their nautical knowledge, so the passage to Africa did not depend on them. Furthermore, Fortune did not smile on him and Alarico died prematurely in Cosenza at the age of 35 (or 40), possibly due to a fever, and his body was, according to legend, buried in the bed of the Busento de accordance with the pagan practices of his Visigothic people. Scholars often wonder about King Alaric's cause of death. Francesco Galassi and his colleagues recently pored over all the historical, medical, and epidemiological sources they could find on the king's death, and concluded that the underlying cause must have been malaria.

They diverted the course of the Busento River as it passed through Cosenza and buried Alarico and his treasure in the riverbed, then returned the river to its normal course and killed the slaves who carried out the work. A similar story it tells about the treasure of Decebalus, buried under a river in the year 106. These burials repeat Scythian models of the lower Danube and the Black Sea.

Alaric was succeeded in command of the Gothic army by his brother-in-law Ataúlfo, who married Honorio's sister, Galla Placidia, three years later. Alaric was father-in-law of the future Visigothic King Theodoric I and father of a daughter who married Brond, King of the Anglo-Saxons. The latter were the parents of Friwin de Morinie, great-grandfather of Cerdic of Wessex, founder of the Royal House of Wessex in England.[citation needed]

Although he is referred to as the first of the Visigothic kings, he was more of a military leader and never set foot on the Iberian Peninsula. The line of Gothic kings properly begins with his successor, cousin and brother-in-law Ataúlfo who, married to Galla Placidia in 414, died in the city of Barcino in 415. The Visigothic Kingdom of Tolosa, as a federated state of Rome (418–476), was based in the Aquitania secunda province, so his policy and military interventions were far from Hispania. However, the interventions of Theodoric I (418-453) in Hispania were numerous, either as a federated people of Rome or on his own initiative. Only after the defeat of the Visigoths in the battle of Vouillé and the period called the Ostrogothic interregnum (507–549), the birth of the Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo took place.

Fonts

The main authorities on Alaric's career are: the historian Orosio and the poet Claudiano, both contemporaries, neither impartial; Zosimus, a historian who lived probably about half a century after Alaric's death; and Jordanes, a Goth who wrote the history of his nation in 551, basing his work on Cassiodorus's Gothic History. The legend of the burial of Alaric in the Buzita river comes from Jordanes.

Contenido relacionado

Bonnie and Clyde

History of the Netherlands Antilles

37th century BC c.