Action potential

An action potential is a wave of electrical discharge that travels along the cell membrane changing its electrical charge distribution. Action potentials are used in the body to carry information between some tissues and others, which makes them an essential microscopic characteristic for life. They can be generated by various types of body cells, but the most active in their use are the cells of the nervous system to send messages between nerve cells (synapses) or from nerve cells to other body tissues, such as muscle or glands.

Many plants also generate action potentials that travel through the phloem to coordinate their activity. The main difference between animal and plant action potentials is that plants use potassium and calcium fluxes while animals use potassium and sodium.

Action potentials are the fundamental pathway of transmission of neural codes. Its properties can slow the size of developing bodies and allow centralized control and coordination of organs and tissues.

General considerations

There is always a potential difference, or membrane potential, between the inside and outside of the cell membrane (usually ~70 mV). The charge of an active cell membrane is kept at negative values (inside with respect to the outside) and varies within narrow margins. When the membrane potential of an excitable cell depolarizes beyond a certain threshold (–65 mV to –55 mV app) the cell generates (or fires) an action potential. It is important to clarify that both the interior and exterior of the cell remain electroneutral, that is, there is no difference in net charge between the interior of the cell and the exterior. The difference in membrane potential is due to the differential distribution of ions (mainly chlorine and sodium on the outside of the cell, and potassium and organic anions on the inside).

| Transmembrane ionic concentrations of a mammal cell | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Ion | External concentration (mM) | Internal concentration (mM) |

| Cathion | Sodium (Na+) | 145 | 5-15 |

| Potassium (K+) | 5 | 140 | |

| Magnesium (Mg2+) | 1-2 | 0.5 | |

| Calcium (Ca2+) | 1-2 | 0.0001 | |

| Hydrogen (H)+) | 0,00004 | 0,00007 | |

| Aniónica | Clone (Cl-) | 110 | 5-15 |

Very basically, an action potential is a very rapid change in membrane polarity from negative to positive and back again, in a cycle that lasts a few milliseconds. Each cycle comprises an ascending phase, a descending phase and finally a hyperpolarized phase. In specialized cells of the heart, such as coronary pacemaker cells, the intermediate voltage plateau phase may occur before the falling phase.

Action potentials are measured with electrophysiology recording techniques (and more recently, with MOSFET neurochips). An oscilloscope recording the membrane potential of a particular point on an axon shows each stage of the action potential—rising, falling, and refractory—as the wave passes. These phases together form a warped sinusoidal arc. Its amplitude depends on where the action potential has reached the point of measurement and the elapsed time.

The action potential is not held at a point on the plasma membrane, but rather travels across the membrane. It can travel along an axon for a long distance, for example carrying signals from the brain to the end of the spinal cord. In large animals such as giraffes or whales, the distance can be several meters.

The speed, frequency, and simplicity of action potentials vary by cell type and even between cells of the same type. Even so, the voltage changes tend to have the same amplitude between them. In the same cell, several consecutive action potentials are practically indistinguishable. The "cause" of the action potential is the exchange of ions across the cell membrane. First, a stimulus opens the sodium channels. Since there are some sodium ions on the outside, and the inside of the neuron is negative relative to the outside, sodium ions quickly enter the neuron. Sodium has a positive charge, so the neuron becomes more positive and starts to depolarize. Potassium channels take a little longer to open; once open, potassium quickly leaves the cell, reversing the depolarization. Around this time, the sodium channels begin to close, causing the action potential to return to -70 mV (repolarization). The action potential actually goes beyond –70 mV (hyperpolarization), because the potassium channels stay open a bit longer. Gradually the ion concentrations return to resting levels and the cell returns to –70 mV.

Underlying mechanism

Resting membrane potential

When the cell is not stimulated by suprathreshold depolarizing currents, it is said to be at a resting membrane potential.

The cell membrane is composed mainly of a highly hydrophobic phospholipid bilayer, which prevents the free passage of charged particles such as ions. Therefore, this phospholipid bilayer behaves like a capacitor, separating charges (given by the ions in solution) at a distance of approximately 4 nm. This allows the maintenance of the membrane potential over time. The membrane potential is due to the differential distribution of ions between the interior and exterior of the cell. This membrane potential is maintained over time by active transport of ions by pumps, such as the sodium-potassium pump and the calcium pump. These proteins use the energy of ATP hydrolysis to transport ions against their electrochemical gradient, thus maintaining the ionic concentration gradients that define the membrane potential.

Phases of the action potential

Variations in the membrane potential during the action potential are the result of changes in the permeability of the cell membrane to specific ions (specifically, sodium and potassium) and consequently changes in the ionic concentrations in the intracellular and extracellular compartments. These relationships are mathematically defined by the Goldman, Hodgkin, and Katz (GHK) equation.

Changes in membrane permeability and the onset and cessation of ionic currents during the action potential reflect the opening and closing of ion channels that form passageways for ions through the membrane. Proteins that regulate the passage of ions across the membrane respond to changes in membrane potential.

In a simplified model of the action potential, the resting potential of a part of the membrane is maintained by the potassium channel. The rising or depolarization phase of the action potential is initiated when the potential-gated sodium channel opens, causing sodium permeability to greatly exceed that of potassium. The membrane potential goes toward ENa. In some cells, such as coronary pacemaker cells, the rising phase is generated by calcium rather than sodium concentration.

After a short interval, the voltage-gated (delayed) potassium channel opens, and the sodium channel gradually closes. As a consequence, the membrane potential returns to the resting state, shown in the action potential as a falling phase.

Because there are more open potassium channels than sodium channels (membrane potassium channels and voltage-gated potassium channels are open, and the sodium channel is closed), potassium permeability is now much higher than before the onset of the ascending phase, when only membrane potassium channels were open. The membrane potential approaches EK more than it was at rest, making the potential refractory phase. The delayed voltage-gated potassium channel closes due to hyperpolarization, and the cell returns to its resting potential.

Threshold and initiation

Action potentials are triggered when an initial depolarization reaches a threshold. This threshold potential varies, but is typically around -55 to -50 millivolts above the resting potential of the cell, implying that the inward current of sodium ions exceeds the outward current of potassium ions. The net flow of positive charge that accompanies the sodium ions depolarizes the membrane potential, leading to an opening of the voltage-gated sodium channels. These channels provide a greater flow of ionic currents inward, increasing depolarization in a positive feedback that causes the membrane to reach high levels of depolarization.

The threshold of the action potential can be varied by changing the balance between sodium and potassium currents. For example, if some of the sodium channels are inactive, a certain level of depolarization will open fewer sodium channels, thus increasing the depolarization threshold required to initiate the action potential. This is the principle of the operation of the refractory period (see refractory period).

Action potentials are highly dependent on the balances between sodium and potassium ions (although there are other ions that contribute in a minor way to the potentials, such as calcium and chloride), and for this reason the models are made using only two transmembrane ion channels: a voltage-gated sodium channel and a passive potassium channel. The origin of the action potential threshold can be visualized in the I/V curve (image) that plots the ionic currents through the channels against the membrane potential. (The I/V curve depicted in the image is an instantaneous relationship between currents. It shows the peak of currents at a given voltage, recorded before any inactivation occurs (1 ms after reaching that voltage for sodium). It is also important to note that most of the positive voltages in the graph can only be achieved by artificial means, by applying electrodes to the membranes).

Four points stand out on the I/V curve indicated by the arrows in the figure:

- The green arrow indicates the rest potential of the cell and the value of the balance potential for potassium (Ek). Because the channel K+ is the only one open with those negative voltage values, the cell will remain in Ek. A stable rest potential will appear with any voltage in which the I/V (green line) summons crosses the null current point (axis x) with a positive slope, as it does in the green arrow. This is because any disruption of the membrane potential to negative values will mean net input currents that will depolarize the cell beyond the crossing point, while any disturbance to positive values will mean net outflows that will hyperpolarize the cell. Thus, any change in the positive slope membrane potential tends to return the cell to the crossing value with the axis.

- Yellow arrow indicates the balance of potential Na+ (ENa). In this two-ion system, the ENa is the natural limit of the membrane potential of which the cell cannot pass. The current values in the graph exceeding this limit have been artificially measured by compelling the cell to surpass it. Still, the ENa It could only be reached if the potassium current did not exist.

- The blue arrow indicates the maximum voltage that can reach the peak of the action potential. It is the maximum membrane potential that the cell in natural state can achieve, and cannot reach the ENa due to the contrary action of potassium flows.

- The red arrow indicates the threshold of action potential. It's the point where Isum is changed to a net inflow. It emphasizes that at this point the net zero flow point is crossed, but with negative slope. Any "negative slope cutpoint" of the zero-flow level on I/V chart is an unstable point. If the voltage at this point is negative, the flow goes outward and the cell tends to return to the rest potential. If the voltage is positive, the flow goes inside and tends to depolate the cell. This depolarization implies greater flow into the interior, making sodium flows real. The point where the green line reaches the most negative value is when all sodium channels are open. Depolarization beyond this point lowers sodium currents as the electrical force decreases as the membrane potential approaches ENa.

The threshold of the action potential is sometimes confused with the threshold of sodium channel opening. This is incorrect, since sodium channels do not have a threshold. Rather, they open in response to depolarization randomly. Depolarization does not imply so much the opening of the channels as the increase in the probability that they will open. Even at hyperpolarizing potentials, a sodium channel can open sporadically. Furthermore, the threshold of the action potential is not the voltage at which sodium ion flux becomes significant; it is the point at which it exceeds the flux of potassium.

Biologically, in neurons depolarization originates in dendritic synapses. In principle, action potentials could be generated at any point along the nerve fiber. When Luigi Galvani discovered animal electricity by bringing a dead frog's leg back to life by touching the sciatic nerve with a scalpel, inadvertently applying a negative electrostatic charge and initiating an action potential.

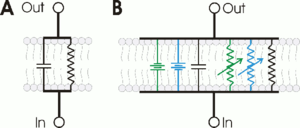

Circuit model

Cell membranes with ion channels can be represented with an RC circuit model to better understand the propagation of action potentials in biological membranes. In these circuits, the resistor represents membrane ion channels, while the capacitor represents membrane lipid insulation. Potentiometers indicate voltage-gated ion channels, as their value changes with voltage. A fixed value resistor represents the potassium channels that maintain the resting potential. The sodium and potassium gradients are indicated in the model as voltage sources (battery).

Propagation

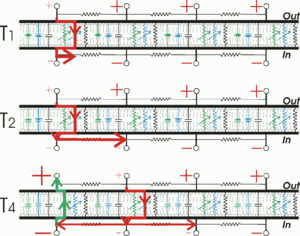

In unmyelinated axons, action potentials propagate as a passive interaction between membrane-traveling depolarization and voltage-gated sodium channels.

When a part of the cell membrane becomes depolarized enough for voltage-gated sodium channels to open, sodium ions enter the cell by facilitated diffusion. Once inside, positive sodium ions drive nearby ions along the axon by electrostatic repulsion, and attract negative ions from the adjacent membrane.

As a result, a positive current travels along the axon, with no ions moving very fast. Once the adjacent membrane is sufficiently depolarized, its voltage-gated sodium channels open, refeeding the cycle. The process is repeated along the length of the axon, generating a new action potential in each segment of the membrane.

Spread Rate

Action potentials propagate faster in larger diameter axons, if all other parameters hold. The main reason for this to occur is that the axial resistance of the lumen of the axon is less the greater the diameter, due to the greater ratio between total surface area and membrane surface area in cross section. As the membrane surface is the main obstacle to potential propagation in unmyelinated axons, increasing this rate is an especially effective way of increasing the rate of transmission.

An example of an animal that uses increased axon diameter as a regulator of the rate of propagation of the membrane potential is the giant squid. The giant squid axon controls muscle contraction associated with the animal's predator-evasion response. This axon can exceed 1 mm in diameter, and is possibly an adaptation to allow very rapid activation of the escape mechanism. The speed of nerve impulses in these fibers is one of the fastest in nature, for those with unmyelinated neurons.:)

Saltatory Driving

In myelinated axons, saltatory conduction is the process by which action potentials appear to jump along the axon, being regenerated only in non-isolated rings (Ranvier nodes).

Detailed mechanism

The main obstacle to the speed of transmission in unmyelinated axons is the capacitance of the membrane. The capacity of a capacitor can be decreased by lowering the cross-sectional area of its plates, or by increasing the distance between the plates. The nervous system uses myelination to reduce the capacitance of the membrane. Myelin is a protective sheath created around axons by Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes, neuroglia cells that crush their cell body and axon respectively, forming sheets of membrane and plasma. These sheets are coiled in the axon, pulling the conducting plates (intracellular and extracellular plasma) away from each other, decreasing the capacitance of the membrane.

The resulting isolation results in rapid (virtually instantaneous) conduction of ions through the myelinated sections of the axon, but prevents the generation of action potentials in these segments. Action potentials only occur again in the demyelinated nodes of Ranvier, which lie between the myelinated segments. In these rings there are a large number of voltage-gated sodium channels (up to four orders of magnitude greater than the density of unmyelinated axons), which allow action potentials to be regenerated efficiently in them.

Due to myelination, the isolated segments of the axon act as a passive wire: they conduct action potentials rapidly because the membrane capacitance is very low, and they minimize the degradation of action potentials because the resistance of the membrane is high. When this passively propagating signal reaches a Ranvier node, it initiates an action potential that travels passively again until it reaches the next node, repeating the cycle.

Damage minimization

The length of the myelinated segments of an axon is important for saltatory conduction. They should be as long as possible to optimize passive conduction distance, but not long enough that the decrease in signal intensity is so great that it does not reach the sensitivity threshold at the next Ranvier node. Actually, the myelinated segments are long enough that the passively propagated signal travels at least two segments while maintaining a signal amplitude sufficient to initiate an action potential at the second or third node. This increases the safety factor of saltatory driving, allowing the transmission to go through nodes in case they are damaged.

Illness

Some diseases affect saltatory conduction and slow the rate of travel of an action potential. The best known of all these diseases is multiple sclerosis, in which damage to myelin makes coordinated movement impossible.

Refractory period

It is defined as the moment in which the excitable cell does not respond to a stimulus and therefore does not generate a new action potential. It is divided into two: absolute (or effective) refractory period and relative refractory period.

The absolute refractory period is that in which the voltage-sensitive Na+ channels are inactive, thus sodium ion transport is inhibited. Instead, the relative refractory period occurs somewhere in the repolarization phase, where Na+ channels gradually begin to reactivate. In this way, adding a very intense excitatory stimulus can cause the channels (which are closed at that moment) to open and generate a new action potential whose amplitude depends on how close the membrane potential is at that moment to the potential. resting potential. The relative refractory period ends after the hyperpolarization (or postpotential) phase in which all voltage-sensitive Na+ channels are closed and available for a new stimulus.

There is also an effective refractory period, which is only seen in cardiac muscle cells (this is because the cells are forming a cell syncytium). In this case, the cell depolarizes normally, but it cannot conduct said stimulus to its neighboring cells. This refractory period is a very useful parameter in the evaluation of antiarrhythmic drugs.

The refractory period varies from cell to cell, and it is one of the characteristics that allow us to tell if a cell is more or less excitable than another. In other cases, such as cardiac muscle, its long refractory period allows it the ability not to tetanize.

Evolutionary Advantage

Regarding the causes for which nature has developed this form of communication, this is answered by considering the transmission of information over a long distance through a nerve axon. To carry information from one end of the axon to the other, physical laws such as those that condition the movement of electrical signals in a cable must be overcome. Due to the electrical resistance and capacitance of the cable, signals tend to degrade along the length of the cable. These properties, called cable properties, determine the physical limits that signals can reach.

The correct functioning of the body requires that the signals arrive from one end of the axon to the other without losses along the way. An action potential not only propagates along the axon, but is regenerated by membrane potential and ionic currents at each membrane narrowing along its path. In other words, the nerve membrane regenerates the membrane potential to its full amplitude as the signal travels down the axon, exceeding the limits imposed by transmission line theory.

Contenido relacionado

Heterocephalus glaber

John Franklin Enders

Alopecurus

![E_{m, K_{x}Na_{1-x}Cl } = frac{RT}{F} ln{ left(frac{ P_{Na^{+}}[Na^{+}]_mathrm{out} + P_{K^{+}}[K^{+}]_mathrm{out} + P_{Cl^{-}}[Cl^{-}]_mathrm{in} }{ P_{Na^{+}}[Na^{+}]_mathrm{in} + P_{K^{+}}[K^{+}]_{mathrm{in}} + P_{Cl^{-}}[Cl^{-}]_mathrm{out} } right) }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0ba09459a33a9b1860b78fc9919e0a737a63a240)