Achalasia

Achalasia consists of the inability to relax the smooth muscle fibers of the gastrointestinal tract at any junction site from one part to another. It is said, in particular, of esophageal achalasia, or the inability of the gastroesophageal sphincter to relax when swallowing, due to degeneration of the ganglion cells in the wall of the organ. The thoracic esophagus also loses peristaltic activity normal and becomes dilated producing a megaesophagus.

esophageal achalasia or simply achalasia is a rare disease in which the esophagus is unable to carry food to the stomach. The disease affects both sexes and can appear at any age, however, it is generally diagnosed between the third and fourth decades of life. Its incidence in the United States and Europe ranges from 0.5 to 1 per 100,000 inhabitants.

History

Sir Thomas Willis is known to have described achalasia in 1679. In 1881, von Mikulicz described the disease as cardiospasm to indicate that the symptoms were due to a functional rather than a mechanical problem. In 1929, Hunt and Rake demonstrated that the disease was caused by a failure of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) to relax and the term achalasia, meaning failure to relax, was coined.

Causes

The real etiology of the disease is not well known, although a part of this disease is characterized by deficiency in the Esophagus#Lower esophageal sphincter, which prevents it from relaxing during swallowing, hindering the entry of food into the stomach. This disease is also characterized by decreased peristalsis.

On the other hand, there is a lack of nerve stimulation to the esophagus, which has various origins, damage to the esophageal nerves, infections (mainly parasites), cancer and even hereditary factors.

It affects people of both sexes and at any age, however it is more frequent in middle-aged adults.

Most cases seen in the United States are primary idiopathic achalasia; however, achalasia can be seen in Chagas disease caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, esophageal infiltration by gastric carcinoma, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, lymphoma, certain viral infections, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Pathogenesis

Contraction and relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) are regulated by excitatory (such as acetylcholine and substance P) and inhibitory (such as nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide) neurotransmitters. Patients with achalasia have a lack of non-adrenergic and non-cholinergic inhibitory ganglion cells, which are often surrounded by eosinophil-predominant leukocytes, causing an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission. The result is an esophageal sphincter. continuously hypertensive or not relaxed.

Clinical picture

The most notable symptoms in achalasia are:

- Retroesternal pain, which in initial stages is intermittent and is becoming progressive.

- Esophageal dysphagia (food, once swallowed, is "attacked" by increased pressure from the distal part of the esophagus and cardias).

- In advanced phases, regurgitation, chest pain, and weight loss can be confused with esophagus cancer.

- Constant reflux, in the most serious case of aggravated esophageal stenosis, a dehydration and malnutrition syndrome is quickly produced that can reach life-threatening levels in less than 5 days due to hypovolemic shock and acute kidney failure.

Diagnosis

Different imaging techniques are used for diagnosis such as: esophagoscopy, radiology and manometry.

Due to the similarity in symptoms, esophageal achalasia can be confused with more common disorders, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, hiatal hernia, physiological disorders, and even psychosomatic disorders.

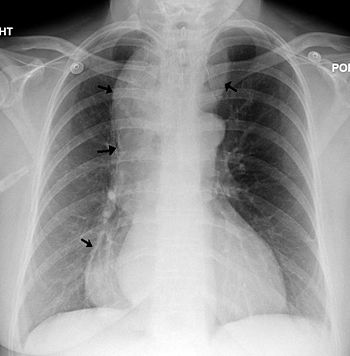

Radiographic appearance

An X-ray esophagram (fluoroscopy) may show decreased perstasis, dilation of the middle and upper (proximal) esophagus, and narrowing of the esophagus at its lower (distal) part, with narrowing of the esophageal sphincter inferior and diameter reduction at the gastroesophageal junction. The image it projects is classically called "parrot-shaped" or "mouse-tailed". Above reduction, the esophagus is often seen dilated to varying degrees as it gradually stretches over time. Due to the lack of peristaltic movements, a margin between air and liquid is usually observed on the radiograph.

Esophageal manometry

The diagnosis is confirmed by high-resolution esophageal manometry, which measures esophageal pressures using a nasoesophageal tube and allows comparison of pressures at baseline and during swallowing. A thin tube is inserted through the nose, and the patient is instructed to swallow several times. The probe measures muscle contractions in different parts of the esophagus during the act of swallowing. Manometry reveals failure of the LES to relax with each swallow and lack of functional smooth muscle peristalsis in the esophagus.

Endoscopy

To rule out «complications», an upper digestive endoscopy is usually performed.

It allows confirming the functional character of the terminal narrowing of the esophagus, by overcoming it by means of a gentle pressure of the endoscope. This does not occur when the narrowing is organic, due to inflammation or neoplasia.

Endoscopy is necessary to rule out other pathologies, before any treatment.

The radioisotopic scintigram is used to quantitatively establish the degree of deterioration of the transport function. It is useful to assess disease progression or therapeutic response.

Treatment

The treatment of esophageal achalasia is still controversial. Current therapies are usually palliative and aim to alleviate dysphagia by disturbing or relaxing the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) muscle fibers with botulinum toxin.

Both before and after treatment, achalasia patients are instructed to eat slowly, chew well, drink plenty of water with meals, and avoid eating close to bedtime. Increasing the inclination of the head of the bed or sleeping with a wedge pillow promotes emptying of the esophagus by gravity. After surgery or pneumatic dilation, proton pump inhibitors can help prevent reflux damage from inhibiting gastric acid secretion. Foods that can aggravate reflux should be avoided, including tomato sauce, citrus fruits, chocolate, mint, liquor, and caffeine.

Medical treatment

Drugs that reduce LES pressure are often helpful, especially as a way to buy time while waiting for surgical treatment, if indicated. Commonly used medications include calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine and nitrates such as nitroglycerin and isosorbide dinitrate. However, many patients experience unpleasant side effects, such as headaches and swollen feet, and these drugs often only start to work after several months.

Botulinum toxin (Botox), produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, can be injected into the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), paralyzing the muscles that keep it closed and stop the spasm. As in the case of cosmetic Botox, the effect is only temporary and symptoms return relatively quickly in most patients. Botox injections almost always cause sphincter scarring, which can increase the difficulty of surgery, called a Heller myotomy, later on. This treatment is only recommended for patients who cannot take the risk of surgery, such as older people in poor health. In one study it was shown that the probability of remaining asymptomatic at 2 years was 90% for surgery and 34% for Botox.

Pneumatic expansion

With pneumatic balloon dilation, muscle fibers are stretched and slightly torn by the force of inflation of a balloon placed inside the lower esophageal sphincter. Treatment consists of dilating the affected part of the esophagus with plugs (Hurst dilators). Gastroenterologists who specialize in achalasia and have performed many of these aggressive balloon dilations achieve better results and fewer perforations. There is always a small risk of a perforation that requires immediate surgical repair. Pneumatic dilation can form scars that can increase the difficulty of the Heller myotomy, if surgery is indicated later. Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) occurs in some patients after pneumatic dilation. Pneumatic dilation is most effective in the long term in patients older than 40 years, while in younger patients the benefits tend to be less durable. Dilation may need to be repeated with larger balloons for maximum effectiveness of the procedure.

Surgery

In many cases, the previous treatments do not have an effect, so surgery is used, which (despite the fear that it poses a surgical risk) is so far the method of choice. A cut is made in the lower esophageal sphincter that can be done by laparoscopy. This intervention is called Heller's myotomy.

The esophagus is made up of several layers, and the myotomy only cuts away the outer muscular layers that hold the esophagus closed, leaving the inner mucosal layer intact. A partial fundoplication or "wrap" in order to prevent excess reflux, which can cause serious damage to the esophagus over time (Dor's Patch). After surgery, patients must follow a bland diet for several weeks to a month, avoiding foods that can aggravate reflux.

Complications and expectations

Surgery generally causes immediate and long-term improvement, while other methods generally produce temporary improvement in symptoms.

This disorder can be complicated, symptoms should not be taken lightly; If proper treatment is not received, it can lead to esophageal perforation, reflux, or aspiration of food into the lungs, causing pneumonia. It may also increase the risk of cancer of the esophagus (esophageal adenocarcinoma) in the long term.

If properly treated, the existing risk is minimal.

Other types of achalasia

- Sphintern acalasia: It is the insufficiency of any sphincter of a tubular organ to relax as a reaction to a physiological stimulus.

- Pelvirrectal acalasia: It consists of the congenital lack of lymph node cells in a distal segment of the large intestine; the loss resulting from normal motor function in this segment causes hypertrophic dilation of the proximal portion of the normal colon.

Contenido relacionado

Rib

Prospect

Adipose tissue