Aboriginal languages of Australia

The Australian Aboriginal languages are a heterogeneous assemblage of language families and language isolates native to Australia and adjacent islands, though initially excluding Tasmania. The parental relationships between these languages are not entirely clear, although substantial progress has been made in recent decades.

The Tasmanian aborigines were wiped out very early in the colonization of Australia and their languages became extinct before they could be documented in detail. Historically, Tasmanians were cut off from the mainland since the late ice ages and apparently remained without outside contact for over 10,000 years. Their language is unclassifiable with the limited data available, although it seems that there were similarities with the languages of the mainland.

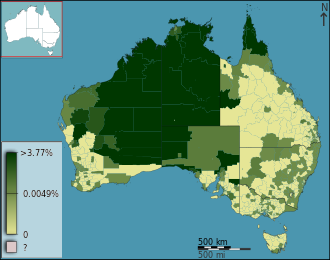

The main family of Australian languages is the Pama-Nungan family and covers almost the entire Australian continent, most linguists (with R.M.W. Dixon as a notable exception) accept Pana-Nung as a phylogenetic unit. For convenience, the other languages, spoken almost all in the far north, have been grouped as non-Pama-ñungan.

The number of speakers of languages from these families is currently very limited, around 50,000 users.

Common features

The Australian languages form a linguistic area that shares a large share of vocabulary and unusual phonology: only three vowels (a, i, u), no distinction between voiced and voiceless, no fricatives, however there are several types of r and plosives, nasals and laterals with various points of articulation — labial p, m, dental th, nh, lh, alveolar t, n, l, retroflex rt, rn, rl, palatal ty, ny, ly, velar k,ng. Dixon believes that after perhaps 40,000 years of mutual influences, it is no longer possible to distinguish deep genealogical relationships from linguistic characteristics in Australia and that even the Pama-Nungan family is not valid.

Other common linguistic features are:

- The words count, almost always, with more than one syllable.

- The names distinguish three numbers (singular, plural and dual). Often the plural is formed by reduplication.

- There are no names for the numerals beyond 3. Although in contrast to the singular and the plural, in many languages there is dual and trial. For numerals above three are used combinations type 2+2 or 2+1, etc.

- These are languages with grammatical cases and a small number of phonemes. Language records adopt extreme varieties.

- The existence of semantic categories systems by prefixes for the nouns is common. Thus, for example, the Enindhilyagwa language (of the non-Pama-ñungana family) has five genres: male, nonhuman, female (human and inhuman), inhuman "brillant" (prefixed) a-... and inhuman "not brilliant" (prefixed) mwa-). In the dyirbal language, every name must be preceded by one of the four categorical words existing in it: bayi (which mainly includes men and animals), Bullet (for women, water, fire and struggle), bullet (for most unedible meat) and baya for everything else.

- Most of them show polysynthetic characteristics.

Spelling

Probably almost all Australian languages with speakers remain without a specific orthography developed for them, using the Latin alphabet for their transcription. Sounds not present in the English language are represented using digraphs, or more rarely by diacritics. Digrams include < rt, rn, rl > for retroflex or (apico)postalveolar, < lh, rh, tn, nh > for (lamino)dentals, < ly, ry, ty, ny > for the (lamino)palatals. Some examples can be seen in the following table:

Language Example Translation Type Pitjantjatjara pana 'ground, soil, country' the diacritic (subrayed) indicates 'n' retrofleja Wajarri nhanha 'this (art.)' the digit indicates 'n' with dental joint Gupapuy/25070/u YolРусскийu 'person, man' 'Русский (from IPA) to watch nasal

Phonology

Australian languages tend to have a vowel system of only three vowel timbres /a, i, u/. The phoneme /u/ is a closed and back vowel, in most languages it is realized as a rounded sound [u] although in other languages it appears as a non-rounded sound [ɯ]. Some languages also present opposition between short and long vowels.

Furthermore, voicing distinctions in consonants are not frequent, depending on whether a plosive is articulated as voiced or voiceless from the position within the word. The syllabic structure is generally simple and usually avoids the occurrence of complicated consonant clusters. A typical consonant inventory for an Australian language typically includes the following phonemes:

Labial dental Alveolar back Palatal Velar Occlusive / p~b /

p/ t /~d / /

th/ t~d /

t/ ~~ / /

rt/ c~ / /

ty/ k~g /

kNasales / m/

m/ n / /

nh/ n/

n/ / /

rn/ / /

ny/ Русский

ngLiquids Gothic / r /

rr/ / /

rside / l / /

lh/ l/

l/ / /

rl/ / /

lySemivocal / w/

w/ j /

and

The previous system stands out for the total absence of fricatives, the existence of a nasal consonant for each plosive (having the same point of articulation). The typical syllable structure is CV(C)

Grammar

Often the Australian languages have morphosyntactic alignments of the ergative type or a mixed one with split ergativity. Other nearly universal features in Australian languages are the existence of at least three numbers (singular, dual, plural) in personal pronouns, the existence of morphological case in nouns, and the existence of a single inflectional category in the verb that fuses tense. grammatical, grammatical mood and grammatical aspect.

Classification

Traditionally, Australian languages have been divided into about a dozen families. Even those who accept that all the languages of Australia are related consider Tiví of Melville and Bathurst Islands (Northern Territory, Australia) to be a likely exception.

The following is an attempt to classify genealogical relationships among Australian families, following the work of Nick Evans and colleagues at the University of Melbourne. Although not all subgroups are mentioned, enough detail is included for the reader to complete the list with any reference work such as Ethnologue. The approximate number of languages is given, but for reference only, as different sources count languages differently.

Note: to make links and references to these languages, keep in mind that many names have several spellings: rr~r, b ~p, d~t, g~k, dj~j~tj~c, j~y, y~i, w~u, u~oo, e~a, etc.

Non-Pama-Nungan Languages

For each family an approximate figure of the number of languages in each family is given, the number differs as different authors differ on whether certain languages are dialects of the same language or different languages.

- Languages allegedly isolated:

- Tiwi (tivi) (about 1,275 speakers in the Bathurst and Melville Islands)

- Giimbiyu (extinct)

- Wagiman (cheering)

- Wardman-Dagoman-Yagman (cheering)

- Proposed families:

- Bunabana (2)

- Daly (four to five families, with between 11 and 19 languages)

- Iwaidjana (3-7)

- Jarrakana (3-5)

- Ñulñulana (nyulnyulana) (8)

- Wororana (7-12)

- Reclassified families:

- Djeragana (3-5 languages in 2 subfamily)

- Recently proposed families:

- Mirndi (5-7)

- Darwin Region (4)

- Arnhem (macrofamily) that includes the gunwinyguana family (22)

- Marrgu-Wurrugu (2, extinct)

- Tasmanian languages

- Western Tasman and Northern Tasmana (extinct)

- Northwest Tasmana (extinct)

- East Tasman (extinct)

Macro-Pama-Nungan languages

The macro-pama-ñungan languages are a recent proposal that groups the pama-ñung languages with two other putative groups, this macrogroup would be formed by:

- Macro-gunwiñwanas (19)

- Tángkica (5)

- Garawa (karawa) (3)

- Pama-ñunganas (properly) (approximately 270 languages, in more than 14 subfamilies).

Contenido relacionado

Socotri language

Mojacar

Stressed Out (A Tribe Called Quest song)

The MA

Joselito