Abbasid Caliphate

The Abasid Caliphate (750-1259), also called the Abasid Caliphate (or Abasid), was a caliphate dynasty founded in 750 by Abu l-Abbas, a descendant of Muhammad's uncle Abbas, who seized power after eliminating the Umayyad dynasty and moved the capital from Damascus to Baghdad. Baghdad became one of the major centers of world civilization during the caliphate of Harun al-Rashid, a character from The Thousand and One Nights.

The Abbasids based their claim to the caliphate on their descent from Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttálib (566-652), one of the younger uncles of the Prophet Muhammad. Muhammad ibn Ali, Abbas's great-grandson, began his campaign for his family's rise to power in Persia, during the reign of the Umayyad Caliph Úmar II. During the caliphate of Marwan II, this opposition reached its climax with the rebellion of the imam Ibrahim, a fourth-generation descendant of Abbas, in the city of Kufa (present-day Iraq), and in the province of Khorasan (in Persia, present-day Iran). The revolt achieved some considerable successes, but Ibrahim was eventually captured and died (perhaps assassinated) in prison in 747. The fighting was continued by his brother Abdullah, known as Abu ul-'Abbas as-Saffah who, after a decisive victory on the Great Zab River (a tributary of the Tigris River that runs through Turkey and Iraq) in 750, he crushed the Umayyads and was proclaimed caliph.

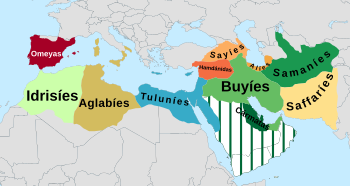

Al-Andalus became independent from the Abbasids under Abd al-Rahmán I in 756, and North Africa became independent in 776. In the 10th century imperial power fell to the Seljuk sultans.

Abu al-'Abbas's successor, Al-Mansur, founded the city of Madinat as-Salam (Baghdad) in 762, to which he transferred the capital from Damascus.

The period of maximum splendor corresponded to the reign of Harun al-Rashid (786-809), from which a political decline began that would be accentuated with his successors. The last caliph, Al-Mu'tasim, was assassinated in 1258 by the Mongols, who had conquered Baghdad. Until that year there were 37 Abbasid caliphs, when the empire was conquered by Hulagu, the grandson of Genghis Khan. However, a member of the dynasty was able to flee to Egypt and retained power under the control of the Mamluks. This last branch of the dynasty remained in Egypt until the Ottoman conquest of 1517.

History

Abbasid Revolution (750-751)

Until the middle of the 8th century the Abbasids had given little to speak of. They were descendants of Abbas, an uncle of the Prophet Muhammad who had not been particularly distinguished in heroic times. Their descendants had supported Caliph Ali, and although they do not appear to have had cordial relations with the Umayyads, they had settled in Humayma, a small Palestinian village. As descendants of Abbas, and thus part of the Banu Hashim clan (the same clan as the prophet), the Abbasids claimed to be the prophet's true successors by virtue of his closest lineage. The Abbasids also attacked the moral character of the Umayyads and their administration in general. According to Ira Lapidus, "The Abbasid revolt was largely supported by Arabs, mainly the aggrieved settlers of Merv with the addition of the Yemeni faction and their mawali (non-Arab converts)". they appealed to non-Arab Muslims, known as mawali, who stood outside the kinship-based society of Arabs and were perceived as an underclass within the Umayyad empire. Muhammad ibn 'Ali, Abbas's great-grandson, began campaigning in Persia for the return of power to the family of the Prophet Muhammad, the Hashimites, during the reign of Úmar II.

Beyond the genealogical subtleties, the fundamental factor was that they knew how to take advantage of the main groups opposed to the Umayyads, who based their ideas on placing a member of the prophet's family in the caliphate. To this end, the Abbasids began to weave a conspiracy in Kufa. In order not to make the mistakes of previous revolts, they went to the border region of Khurasan, where many Arabs had emigrated, sending Abu Muslim. This was a mysterious character who claimed that the Umayyads had brought oppression, so a member of the prophet's family was needed to lead the Muslim community and avenge the atrocities committed by the Umayyads without revealing the instigator of the revolt. It was Ibrahim ben Muhammad ben Ali who was waiting for the evolution of events in Humayma.

Many people joined Abu Muslim's army. The rest is military history: in 748, taking advantage of the chaotic situation in the empire of Marwan II, Abu Muslim conquered Merv, a year later Kufa and shortly after he won the battle of Zab. Meanwhile Ibrahim ben Muhammad ben 'Ali is captured and killed and when the rebels enter Kufa, his successor Al-Saffah (750-754), also known as Abu al-'Abbas Abdulah ibn Muhammad as-Saffah or Abul -'Abbas al-Saffah, was proclaimed caliph.

Finally the secret of who that successor was had been revealed, and there is evidence that some were greatly disappointed. To counteract this loss of support, Al-Saffah did everything possible to win over the warlords who had formed the backbone of the old Umayyad army. In addition, the circumstances in which the ascension had taken place required having more support, which became very clear when the death of Al-Saffah, after only four years in office, the question of succession was raised, which pitted a brother of the deceased, Abu Já'far, known as Al-Mansur, with his uncle Abdallah. The crisis was decided by arms and if Al-Mansur was finally able to proclaim himself caliph (754-775) it was thanks to the determined support that Abu Muslim and his Khorasanis gave him. But still the new caliph could not afford to be grateful and executed Abu Muslim using tricks. Then, fearing new riots among his relatives, he ordered several of his uncles to be imprisoned and his relatives and relatives killed.

During his reign, the country's economy improved, reaching great prosperity, Arabic was introduced as the official language, and letters and sciences flourished under his reign. He was the founder of Baghdad, Madinat al-Salam. He died near Mecca during the pilgrimage.

8th century

Al-Mansur is succeeded by his son Al-Mahdi (775-785), who knew how to maintain and increase the rich caliphate he inherited from his father. He continued with the improvements started by his father, improving the food and textile industry and the quality of housing. Meanwhile, the Byzantines, taking advantage of the internal struggles since the beginning of the Abbasid Caliphate, gradually took over Syria, so that in the end the Caliph sent troops, forcing the Empress Irene to sign peace and pay an annual tribute. In Khorasan, where Islam was not consolidated, the warrior Al-Muqanna, with the idea of reviving Persian ideals, faced the Abbasids, eventually conquering Transoxania. The caliph's armies managed to defeat him and Al-Muqanna committed suicide.

Al-Mahdi wanted his youngest son, Haroun, to succeed him, but his eldest son did not agree and he confronted his father, who was killed en route to battle against his son. He is then succeeded by his eldest son, Musa al-Hadi, who intended to appoint his son as heir, excluding his brother Haroun from the line of succession, but died before doing so. The famous Haroun al-Rashid (786-809) is the Abbasid caliph who best illustrates the heyday of the dynasty. He was very careful to call for jihad to spread Islam in Anatolia, although he did not go very far. He surrounded himself with great luxury and pageantry, distancing himself from his subjects and calling himself "the shadow of Allah on earth."

He had to face several rebellions: the Kharijites took Mosul twice but were subdued and the caliph ordered the demolition of the walls that surrounded it. The Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros I refused to pay the tribute and had to be forcibly forced. The Berbers revolted again in Ifriqiya, and in Fez a rebel named Idris founded the independent kingdom of the Idrisids. An army of Ibrahim al-Aglab headed there, who revolted in Tunisia and founded the Aghlabid dynasty, with its capital in Qayrawān (Cairuan). Most of the revolts were quelled with great forcefulness, which is why they were followed by a period of calm. There was a cultural renaissance and Arabic translations of Greek, Persian and Syriac texts were made and based on that knowledge great scientific advances were made. Industry and commerce also boomed.

At this moment the beginning of the decline of the caliphate occurs. Provinces such as Ifriqiya and Al-Andalus gradually became independent and Rafi ben Layt rose up in Samarkand and, in a short time, made Transoxania independent. In Khorasan the Kharijites revolted and the caliph himself came to quell the revolt, but he died before arriving.

Fourth Fitna

However, the most important aspect that marked the caliphate of Harun al-Rasid was the question of succession. In the year 803, just before delivering his formidable blow against the Barmakids, the caliph made public the terms in which the succession would take place: one of his sons, Al-Amin, would become caliph with the support of the army stationed in Baghdad; His second son, Al-Mamoun, was to receive the province of Khurasan, and even though he was to be loyal to his brother, his government was independent in practice. Barely two years after the death of their father, his two sons became embroiled in a catastrophic civil war, known as the Abbasid Civil War or Fourth Fitna. The culminating episode of this war was the siege of Baghdad by troops of Al-Mamun (813-833), which surrendered in 813. This surrender did not bring the end of the war, which lasted until 819 due to the caliph's decision to name Ali ibn Musa, known as Al-Moussa, as his heir. Rida ('the chosen one') for being a direct descendant of Ali. In the end, and for somewhat obscure reasons, the caliph himself put an end to the conflagration. After getting rid of the Persian elements that until then made up his political circle, he decided to return to Baghdad. Al-Rida was "conveniently" poisoned (he is considered a martyr by Twelver Shiites) and central authority restored.

9th century

The political upheavals that opened the ninth century were not the only ones that hit the empire. Behind them, and sometimes clearly interrelated, there were important social convulsions that are now manifesting themselves with great virulence and geographical extension.

One of the reasons for these upheavals was the grim situation of the peasants. Subjected to strong tax pressure, they were forced to pay cash for the crops, which meant selling them at a lower price every time the fiscal agents had the chance to appear in their village. The refusal or delay in payment were punished with exemplary harshness and the only way out was to flee their lands, which caused the communities to be left with fewer members and with the same amount to pay.

In some cases, the social revolts acquired overtones of religious movements. This is the case of the revolts that took place in Khurasan and that were based on the memory of the charismatic figure of Abu Muslim, who inspired a doctrine of groups known by the generic name of Jurrumiyya. Their doctrines gave Abu Muslim the rank of prophet, denied the resurrection, believed in the transmigration of souls and preached the community of women, beliefs directly inherited from Mazdakism, the great social and religious movement that had shaken the Persian community in the VI century.

The social and political upheavals of the 9th century also brought about the weakening of the old Khurasani army that had brought to power the Abbasid family. The Al-Mamoun caliphate witnessed the rise of a member of the Abbasid family who knew best how to notice these changes, Al-Mutasim. This character achieved notoriety thanks to his ability to surround himself with a private army made up of a few thousand soldiers, mostly Turks from territories beyond the borders of the empire.

To put down the Kharijite revolts in Khurasan, such as the one led by Babak Khorramdin, he sent an army officer, Táhir, who put down the revolt and ruled the area with great success to later become independent. Upon his death, his son established the Tahirid dynasty in the area (822). He also had to deal with the Shiites of Kufa and Basra and favor the Mu'Tazilis, whose ideas coincided with his intellectual character. This caused many tensions, as well as the arrest of Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal, the founder of Hanbalism, who became a hero to many. Al-Mamoun tried to put an end to these discontents by renewing the pact with the Shiites and naming the Shiite imam Al-Rida as its heir. Baghdad did not like this decision and the people rose up, proposing Ibrahim, son of Al-Mahdi, as a candidate.

The caliph died on his way to confront the Byzantines and was succeeded by his brother Al-Mu'tásim (833-842). In this caliphate internal rebellions and insecurity increased. His trusted personal guard was made up of Turkish slaves who rose through the ranks of the administration, prompting protests from the Baghdad population. For this reason, a new capital, Samarra, was built 100 km from Baghdad, but unlike it, it was not successful. Turkish officials were acquiring more power, to the point that the life of the caliph and the government came to depend on them. Some Turkish officials (emirs) became independent and created their own states. In addition, the luxurious life that the caliph led had to be paid for by extorting officials.

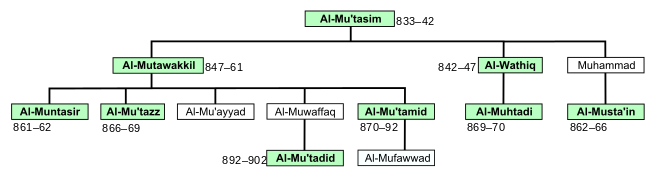

He was succeeded by his son Al-Wáthiq (842-847) and by his brother Al-Mutawákkil (847-861). The latter carried out a repressive government. In the year 849 he annulled the decrees that favored the Mutazilis and released the prisoners for religious reasons. He persecuted Shiites and sought support from Orthodoxy, to which he gave senior positions in the administration. He also persecuted Christians and Jews. To escape Turkish pressure, he had a grandiose palace called Al-Gafariyya built on the outskirts of Samarra, but this change did not prevent him from being assassinated in 861, the victim of a plot by one of his sons and several Turkish officials.

This death signaled a change in relations between the caliphs and their Turkish military "slaves." During the previous period the caliphs had been able to exercise absolute control over these soldiers, but as time passed, this power was diminishing. For nine years after this assassination (861-870), the Abbasid Caliphate was plunged into utter chaos. Four caliphs followed one another during this period, all assassinated and in a virtual state of civil war.

As a consequence of the weakness of the Abbasid power, the situation in the territories of Islam changed radically. This meant that when the caliphate was able to overcome its internal crisis in the years after 870, it was no longer possible for them to send governors to the provinces and calmly wait for them to collect taxes and maintain order: in the face of the fait accompli that local powers they had a solid establishment in their provinces, the caliphs of Baghdad had no choice but to make these local rulers recognize and get them to send the collections of their area. But the disintegration process was already irreversible. In fact, Ahmad ibn Tulun (governor of Egypt appointed in 868) further challenged the government by extending his rule to Palestine and Syria as well, where he ruled for 37 years.

Despite having all these elements against it, during the last 30 years of the 9th century, the Abbasid caliphate experienced a fleeting recovery at the hands of Al-Muwaffaq, who paradoxically never served as caliph. His achievement was to unite around himself the main commanders of the Turkish army. With this political vision, Al-Muwaffaq allowed his brother Al-Mutámid (870-892) to rule, although in the end this caliph was relegated to a mere role as a troupe. Both brothers died one after the other in 891 and 892. A son of Al-Muwaffaq known as Al-Mutádid (892-902) was proclaimed caliph. The years of his government were marked by struggles on all fronts, which in some cases were successful (Syria and northern Mesopotamia and Egypt). This was not the case in eastern Iran, which passed into the hands of the Samanid emirate.

Despite all this, by the turn of the X century, the Abbasid Caliphate seemed to have returned to its heyday; even the samaníes (independent governors), had to recognize the caliphal sovereignty. However, this momentary resurgence was due to the good government of a few caliphs. As soon as power passed into the hands of less gifted caliphs, this entire imposing edifice collapsed with astonishing ease.

Empire Organization

The Abbasids, raised to power by a movement that had its main assets in its ideological component and military potential, were able to impose a high degree of centralization in the entire empire, with the exception of Al-Andalus. and North Africa.

The claim that the Abbasids were members of the prophet's family fully legitimized the dynasty; Thus, they were not criticized for the dynastic succession and only had to face the supporters of Ali's branch, who were disappointed with the way of governing the caliphs and annulled the pact signed with the Abbasids. In these confrontations Muhammad, the great-grandson of the prophet, who became strong in Medina, and his brother Ibrahim, who had revolted in Basra, died. Apart from family, the Abbasids had strong support: the mawali attached to the Abbasid lineage who were employed in the central and provincial administration. Some of the mawalis went on to form families of servants of the administration. The Barmakids became legendary in power and influence within the administration, until in 803 all this came to an end. Caliph Haroun al-Rashid sent the family into a tailspin, imprisoning some and killing others.

The military aristocracy was also of great importance, since the army began to be organized according to the criteria of the geographical origin of the troops, and not in fictitious tribal affiliations as in the Umayyad era. There are political changes of marked Persian influence: the Abbasid caliphs held the religious and political leadership. They surrounded themselves with a great hierarchical ceremonial that was supervised by a chamberlain, they left government tasks in the hands of a grand vizier, with full powers, who presided over a council made up of the heads of the different diwan or administrative departments.

Diwan al-harag: was in charge of the state treasury, administered the revenue collected from the taxes and fees to which the caliphate was subject. During this period, taxes were generalized and levied on all Muslims (tithe of their crops) and on the rest of the population. Imports and exports were also taxed.

Diwan al-nafaqat: regulated palace expenses.

Diwan al-tawqid: handled the caliph's correspondence.

Diwan al-barid: in charge of official communications and secret information.

Diwan al-shurta: was in charge of maintaining order. In the cities a chief of police, sahib al-shurta, was in charge of the policemen who kept order. On the other hand, Al-Muhtasib was in charge of surveillance in the markets. In the provinces, authority was held by a governor and a superintendent, with a certain degree of autonomy, but controlled by the postmaster.

The Abbasids called all these changes dawla ('revolution of fortune').

Disintegration

It is very significant that this disintegration occurs at the moment when Islam is assumed by the majority of the populations that inhabit the area. Until then, Islam became the predominant religion among the indigenous peoples conquered by the Arabs three centuries before. This spread of faith brought greater ideological uniformity, but sectarian divisions were also accentuated.

The definitive crisis of the Abbasid caliphate took place between 908 and 945. During this period, five caliphs succeeded each other in Baghdad, four of whom were deposed by violent means. The events and political ups and downs that marked this crisis were complex. In fact, it was the intrigues of a faction of the civil bureaucracy that allowed one of the weakest and most easily manageable members of the Abbasid lineage, Al-Muqtádir (908-932), whose government was controlled by the viziers, to be proclaimed caliph., from rival groups that were fighting to monopolize fiscal resources. The assassination of this caliph was the consequence of the crisis of central power and unstoppably unleashed the spiral of internal crisis.

The lack of resources had complex roots. To deal with tax collection, the caliphs used the tenants, families who advanced a sum to the caliph (the estimate of what could be collected in a certain area) and then they were responsible for collecting taxes from the citizens.. These tenant farmers usually gave less than they actually collected, so they amassed vast fortunes and exploited the peasants however they could to gather more profit. Trapped by the central government by the imperative need to make payments, especially to an army always ready to rebel, it had to give in to pressure and allow the military to collect the taxes themselves. This gave rise to the granting of iqtá (igar), which implied the granting of territories in which agents of the central government could not exercise their authority, but rather the beneficiary collected the taxes and sent the caliph an amount fixed in advance that was no more than a symbolic amount. During this period, the ilya or himaya also became frequent, where a peasant placed himself under the protection of a lord, ceding his land to him. With this, the peasants sought to protect themselves from the arbitrariness of fiscal agents and from the convulsions caused by wars. In some areas it helped to impose a servile situation on rural populations.

In January 946 Ahmad b. Buya made his entry into Baghdad at the head of a victorious army. The Abbasid caliph on duty had no choice but to hand over effective power to him, putting an end to several decades of struggle in which the chiefs of the army had seized all power. This family, the Buyids, were from Dailam (northern Iran). Three Buyid brothers, Ali, Ahmad and Hasan knew how to take advantage of this moment of weakness and recruited an army made up of Dailamis, accumulating military successes all the way to Baghdad. They forced the caliph to give them grandiose titles and entrust them with the government of the territories they had conquered. They had to establish a system of iqtas and recruit Turks for their army, a system that survived until the arrival of the Seljuks. One of the features that has most attracted attention about the Buyids is the fact that, despite being Shiites, they did not show any predisposition against the Abbasid Caliphate and would allow them to survive, although obviously reduced to a symbolic role and that, paradoxically, in this period it would become the spiritual point of reference for all Sunni Muslims.

The Abbasid caliph, increasingly relying on the Turkic tribes, asked the Seljuks for help in driving the Buyids out of Baghdad. In 1055 the Seljuks conquered the city and allied with the Abbasids. The caliph, whose power was nominal, appointed the Turkish chief, Tughril Beg King of East and West, and the Turks became rulers of the empire. They ruled in a repressive and intolerant way with the different ideas and religions that governed the caliphate, which they plunged into a definitive decadence. The Turks gave in and shared the caliphate in 1055. The successors to Abbasid hegemony had to face more external threats, such as the Hamdanids (northern Mesopotamia and part of Syria), whose origins are a much earlier Arab tribe that, coinciding with With the crisis of the Caliphate, he consolidated his lineage and seized Mosul, coming into direct conflict with the Buyids. This was joined by the taking of Aleppo (944) by Sayf al-Dawla. The branch that ruled in Mosul survived until 979, when it was eliminated by the Buyids. Its border with the Byzantine empire was also contentious, although its end came with the arrival of the Fatimids.

Military resurgence

Although Caliph Al-Mustárshid was the first to raise an army capable of facing the Seljuk, he was finally defeated in 1135 and assassinated. Caliph Al-Muqtafi II was the first of the Abbasids to regain full military independence from the Caliphate, with the help of his vizier Ibn Hubayra. After almost 250 years of subjugation to foreign dynasties, he successfully defended Baghdad against the Seljuks in the 1157 siege of Baghdad, giving him control of Iraq. The reign of Al-Násir (d. 1225) extended the rule of the caliphate to the entire country, thanks in large part to the futuwwa organizations of the Sufis, which the caliph headed. Al-Mustansir built al-Mustansiriya University in an attempt to outshine the Nizamiyya University, built by Nizam al-Mulk during the period of Seljuk rule.

Invasion of the Mongols

In 1206, Genghis Khan established a powerful dynasty among the Mongols of Central Asia. During the 13th century, this Mongol empire conquered almost all of Eurasia, including both China in the east, as well as much of the former Islamic Caliphate and Kievan Rus. in the West. The destruction of Baghdad in 1258 by Hulagu Khan is traditionally considered the approximate end of the Golden Age. The Mongols feared that supernatural punishment would befall them if they shed the blood of Al-Musta'sim, a direct descendant of Baghdad's uncle. Muhammad and last Abbasid Caliph of Baghdad. The Shiites of Persia indicated that such a calamity had not occurred after the death of the Shiite Imam Hussein; however, as a precautionary measure and in accordance with a Mongol taboo against shedding royal blood, Hulagu ordered Al-Musta'sim to be wrapped in a carpet and trampled to death by horses on February 20, 1258. The caliph's immediate family was also executed, with the exception of his youngest son, who was sent to Mongolia, and a daughter who became a slave in Hulagu's harem. According to Mongolian historians, the surviving son was married and had children.[citation needed]

Features of the period of the Abbasid dynasty

The period of the Abbasid dynasty was one of expansion and colonization.

They created a great and brilliant civilization. Trade grew, cities flourished. Extraordinary achievements were made in architecture and arts in general.

Baghdad was a great commercial center. The tales of A Thousand and One Nights reflect the splendid life of this city.

There is a great deal of intellectual activity: history, literature, medicine, Greek mathematics including algebra and trigonometry, geography, etc. Great importance of jurisprudence.

With the Abbasids in power, the last Umayyad moved to Al-Andalus, where he assumed the title of emir. His descendants would secede, creating an independent caliphate.

List of Abbasid Caliphs of Baghdad

| Califa abasi | Queen | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Abul-‘Abbás al-Saffaḥ (721-754) | 750-754 | Revolution down |

| Al-Mansur (712-775) Al-Mahdi (744-785) Al-Hadi (764-786) Harún al-Rashid (763-809) Al-Amín (787-813) Al-Mamún (786-833) Al-Mutásim (796-842) Al-Wáthiq (812-847) Al-Mutawákil (821-861) | 754-775 775-785 785-786 786-809 809-813 813-833 833-842 842-847 847-861 | Splendor abasi |

| Al-Muntásir (837-862) Al-Musta'ín (836-866) Al-Mu'tazz (847-869) Al-Muhtadi (-870) | 861-862 862-866 866-869 869-870 | Anarchy of Samarra |

| Al-Mu'támid (-892) Al-Mu'tádid (857-902) Al-Muktafi (878-908) | 870-892 892-902 902-908 | Abbasis rebirth |

| Al-Muqtádir (895-932) Al-Qáhir (899-950) Al-Muqtádir (895-932) Al-Qáhir (899-950) Ar-Radi (909-940) Al-Muttaqui (908-968) | 908-929 929 929-932 932-934 934-940 940-944 | Fragmentation period |

| Al-Mustakfi (905-946) Al-Muti (913-974) At-Ta'i (932-1003) Al-Qádir (947-1031) Al-Qa'im (1001-1075) | 944-946 946-974 974-991 991-1031 1031-1075 | Low influence of the búyida dynasty |

| Al-Muqtadi (1056-1094) Al-Mustázhir (1078-1118) Al-Mustárshid (1092-1135) Ar-Ráshid (1109-1138) | 1075-1094 1094-1118 1118-1135 1135-1136 | Under the influence of the Seljucida dynasty |

| Al-Muqtafi II (1096-1160) Al-Mustányid (1124-1170) Al-Mustadí (1142-1180) An-Násir (1158-1225) | 1138-1160 1160-1170 1170-1180 1180-1225 | Military downturn |

| Az-Záhir (1175-1226) Al-Mustánsir (1192-1242) Al-Musta'sim (1213-1258) | 1225-1226 1226-1242 1242-1258 | Mongol and final invasion of the Baghdad caliphate |

| Al-Mustánsir II (c.1210-1261) Al-Hákim I (c.1247-1302) Al-Mustakfi I (1285-1340) Al-Wáthiq I (-1341) Al-Hákim II (-1352) Al-Mu'tádid I (-1362) Al-Mutawákil I (-1406) Al-Musta'sim (-1389) Al-Mutawákil I (-1406) Al-Wáthiq II (-1386) Al-Mu'tásim (-1389) Al-Mutawákil I (-1406) Al-Musta'in (1390-1430) Al-Mu'tádid II (-1441) Al-Mustakfi II (1388-1451) Al-Qa'im II (-1458) Al-Mustányid (-1479) Al-Mutawákil II (1416-1497) Al-Mustamsik (-1521) Al-Mutawákil III (-1543) Al-Mustamsik (-1521) Al-Mutawákil III (-1543) | 1261 1262-1302 1302-1340 1340-1341 1341-1352 1352-1362 1362-1377 1377 1377-1383 1383-1386 1386-1389 1389-1406 1406-1414 1414-1441 1441-1451 1451-1455 1455-1479 1479-1497 1497-1508 1508-1516 1516-1517 1517 | Cairo Abbasid Caliphate under the protection of the Sultanate Mamluk of Egypt |

Contenido relacionado

Bike bark

Vincent van Gogh

Manuel Bulnes