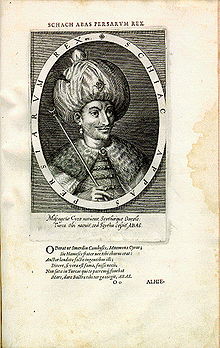

Abbas the Great

Shah 'Abbās I the Great (Persian: شاه عباس بزرگ), better known as Abbas the Great (Herat, January 27, 1571 - Mazandaran, January 19, 1629), was Shah of Iran from 1588 until his death, and the most eminent ruler of the Safavid dynasty.

Although Abbas would preside over the pinnacle of Iran's military, political and economic power, he came to the throne during a troubled time for the Safavid Empire. Under the rule of his ineffectual father, the country was mired in discord between the various factions of the Qizilbash army, which murdered Abbas's mother and older brother. Meanwhile, Iran's enemies, the Ottoman Empire (its archrival) and the Uzbeks, took advantage of this political chaos to seize territory. In 1588, one of the Qizilbash leaders, Murshid Qoli Khan, overthrew Shah Mohamed in a coup and placed the 16-year-old Abbas on the throne. However, Abbas did not take long to seize power.

Under his leadership, Iran developed the Ghilman system in which thousands of Circassian, Georgian, and Armenian slave soldiers were incorporated into the civil administration and military. With the help of these newly created strata in Iranian society (initiated by his predecessors but significantly expanded during his rule), Abbas managed to eclipse the power of the Qizilbash in the civil administration, the royal household, and the military. These actions, as well as his reforms of the Iranian Safavid Dynasty Army, enabled him to fight the Ottomans and Uzbeks and reconquer Iran's lost provinces, including Kakheti, whose people he subjected to large-scale massacres and deportations. By the end of the Ottoman-Safavid War (1603-1618), Abbas had regained possession of Transcaucasia and Dagestan, as well as swaths of Eastern Anatolia and Mesopotamia. He also recaptured land from the Portuguese and Mughal empires and expanded Iranian rule and influence in the North Caucasus, beyond the traditional territories of Dagestan.

Abbas was a great builder and moved the capital of his kingdom from Qazvin to Isfahan, making the city the pinnacle of Safavid architecture. In his later years, following a court intrigue involving several Circassian leaders, Abbas became suspicious of his own sons and had them killed or blinded.

Biography

Abbas was born as the third son of Shah Mohammed Khodabanda in a Safavid Empire that had weakened significantly during his father's reign, which had allowed usurpations and the formation of internal fiefdoms by the Qizilbash emirs, leaders of the Turkmen tribes that constituted the skeleton of the Safavid army. In addition, Ottoman and Uzbek raids were sweeping through the western and eastern provinces. In the midst of this general anarchy, Abbas was proclaimed governor of Khurasan in 1581.

Ascension to the throne and war against the Uzbeks

In October 1588, he obtained the throne of Persia after rebelling against his father Muhammad and imprisoning him, which he achieved with the help of Morshed Gholi Ostajlou, whom he later assassinated in July of the following year. Determined to rise above his country's misfortune, he made a separate peace with the Ottomans (1589-1590), including the cession of large areas of western and northwestern Persia, but, at the same time, directed his efforts against the predatory tide of the Uzbeks, who then occupied and plundered Khurasan. Despite this, it took Abbas almost ten years before he was able to launch a definitive offensive. This delay was caused by his decision to raise a standing army.

The cavalry of the Safavid army, unlike the levied Qizilbash tribal cavalry of bygone days, consisted mainly of Christian Georgians and Armenians and the descendants of Circassian prisoners. The infantry corps of the army were made up of peasants.

Budgetary problems were resolved by returning to the Shah control of the provinces ruled by the Qizilbash chiefs, and sending the revenue from them directly to the royal treasury. In these provinces the Ghulāms were appointed as new governors.

After a long and complicated struggle, Abbas recaptured Mashhad, defeating the Uzbeks in a major battle near Herat in 1597, which drove them as far as the Oxus River. Meanwhile, taking advantage of the death of Tsar Ivan the Terrible in 1584, he had appropriated the provinces south of the Caspian Sea, which had been dependent on Russia up to that time.

He then moved his capital from Qazvin to the more central and more Persian Isfahan in 1592, beautifying the latter with a magnificent series of new mosques, baths, universities and caravansarai, making Isfahan one of the most beautiful cities in the world. world.

War against the Ottomans and conquest of the Persian Gulf

Some years later, in 1599, the mercenary English knight Robert Shirley and the Shah's favorite ghulam, Allahverdi Khan led a far-reaching reform of the army. The massive introduction of muskets and artillery meant a great advance over the old days. With this new army, Abbas launched a campaign against the Ottomans in 1603. In the following year he won his first victory, which forced the enemy to return the territory he had seized, including Baghdad. In 1605, after the victory at Basra, he extended his empire beyond the Euphrates. He also forced Sultan Ahmed I to cede Shirvan and Kurdistan to him in 1611. Hostilities ceased in 1614, with a Persian army in full swing.

In 1615, Abbas murdered more than 60,000 Georgians and deported more than 100,000 of them to Tbilisi after a rebellion. In 1618 he utterly defeated the combined Turkic and Tatar armies near Sultanieh, achieving a peace on very favorable terms for Persia. Baghdad fell to him after a year's siege in 1623. With the support of the British fleet, Abbas took the island of Hormuz from the Portuguese. Much of the trade was diverted to the city of Bandar Abbas, conquered from the Portuguese in 1615, and renamed after the shah.

For these reasons, the Persian Gulf opened up to a flourishing trade with the merchant fleets of the Catholic Monarchy, the Holy Empire, France and England, which enjoyed special privileges. The agents who dealt with the Westerners were mostly of Armenian nationality. Trade and travel experienced a strong boost throughout the Empire.

Times of reform

Abbas's reign, with its military successes and efficient administrative system, elevated Iran to the status of a great power. Abbas was an experienced diplomat, tolerant of his Christian subjects in Armenia. He sent Robert Shirley to Italy, Spain, and England for the purpose of creating a pact against the Ottomans. Allied with Spain, he attacked the Turks by land while Álvaro de Bazán, in command of the galleys of Naples, sacked the ports of Zante, Patmos and Durazzo.

Mistrustful of the once-ruling Qizilbash class, Abbas garnered strong support from the popular classes. Sources say that he spent much of his time with them, personally visiting the bazaars and other public places in Isfahan. The capital had become the center of Safavid architectural progress, with the Royal Mosque, Sheikh Lotfolá's oratory and other monuments such as the Ali Gapú palace, the Chehel Sotún palace and the Naqsh-e Jahán square. His canvas painters (of the Isfahan school, founded under his patronage) created some of the most exquisite works in modern Persian art history, with such illustrious painters as Reza Abbasi, Mohammed Qasim and others.

His power was more absolute than that of the Sultan of Turkey. While the Sultan was limited by the dictates of Muslim religious laws, as interpreted by the religious leader of the kingdom, the Sah Safávida was not thus limited. Suya was the theocracy, in which the Sah, as the representative of the magnets, had absolute power, both temporal and spiritual. He was known as Morshed-e Kamel (the most perfect leader... and as such, he could not be mistaken. He was the referee of religious law. Later, when the Persian kings fell into weakness, the interpreters of religious laws, the Mujtaheds, dominated both religion and temporal affairs. |

Despite the ascetic roots of the Safavid dynasty and the religious interference that restricted pleasures and subjected the law to faith, the art of Abbas's time denotes a certain relaxation of the structures. Historian James Saslow thus interprets the portrait of Muhammad Qasim (above), which flouts the Muslim taboo against wine as well as the intimacy of two men. Also contemporary observers at the Shah's court reported the persistence of similar customs. Among these, nineteen-year-old Thomas Herbert, secretary to the British ambassador, who recounted seeing "boys dressed in gold with rich turbans and sandals, with blond hair falling over their shoulders and vermilion-painted cheekbones".

Abbás died in Mazandaran in 1629. His domains stretched from the Tigris to the Indus, always exceeding the Persian borders of pre-Islamic times. He is still a very popular figure in Iran today, appearing in numerous traditional tales. His fame is marred, however, by numerous allegations of tyranny and cruelty, especially against his own family. Fearing a coup carried out by some relative (such as the one he himself carried out against his own father), he locked his family inside the palaces to keep them away from contact with the outside world. This resulted in weak successors. Abbas murdered his eldest son, Safi Mirza, leaving his grandson Safi on the throne. It is believed that Safi Mirza was assassinated because the Shah had read the story of King Absolom, who rebelled against his own father, as described in the illustrations to the Morgan Crusader Bible, which was sent to him as a gift by Cardinal Maciejowski in 1604.

Family

- Consorts

- A circasian concubine, mother of Mohammad Baqer Mirza;

- Fakhr Jahan Begum, daughter of King Bagrat VII of Kartli and Queen Anna of Kakheti, and mother of Zubayda Begum; {sfnintMikaberidze782015Syp=61}}

- A daughter of Mustafa Mirza (m. 1587), daughter of Mustafa Mirza, son of Shah Tahmasp I;

- Olghan Pasha Khanum (m. 1587), daughter of Husayn Mirza, son of Bahram Mirza Safavi, and widow of Hamza Mirza;

- Yakhan Begum (m. 1 September 1602), daughter of Khan Ahmad Khan and Maryam Begum;

- Princess Helena, daughter of King David I of Kakheti and Queen Ketevan the Martyr;

- Fatima Sultan Begum also known as Peri and Lela, a single Tinatin (house in 1604 - div.), daughter of King George X of Kartli and Queen Mariam Lipartiani;

- A sister of Ismail Khan, a circasian, and Abbas's favorite wife;

- A daughter of Shaykh Lotfullah Maisi, a Shiite theologian;

- Tamar Amilakhori, daughter of Faramarz Amilakhori and sister of Abd-ol-Ghaffar Amilakhori;

- Children

- Mohammad Baqer Mirza (15 September 1587, Mashhad, Khorasan - killed on 25 January 1615, Rasht, Gilan), was governor of Mashhad 1587-1588, and Hamadan 1591-1592. He married first in Isfahan, 1601, with Princess Fakhr Jahan Begum, daughter of Ismail II, and secondly with Dilaram Khanum, a Georgian. He had descendants, two children:

- Sultan Abul-Naser Sam Mirza, happened as Safi - with Dilaram;

- Sultan Suleiman Mirza (assisited in August 1632 in Alamut, Qazvin) - with Fakhr Jahan;

- Sultan Hasan Mirza (September 1588, Mazandaran - August 18, 1591, Qazvin);

- Sultan Mohammad Mirza (18 March 1591, Qazvin - dead in August 1632, Alamut, Qazvin) Blind by order of his father, 1621. She had a descendant, a daughter:

- Gawhar Shad Begum, married to Mirza Qazi, the Shaykh-ul-Islam of Isfahan;

- Sultan Ismail Mirza (6 September 1601, Isfahan - dead on 16 August 1613);

- Imam Qoli Mirza (12 November 1602, Isfahan - dead in August 1632, Alamut, Qazvin) Blind by order of his father, 1627. He had descendants, a son:

- Najaf Qoli Mirza (c. 1625 - dead August 1632, Alamut, Qazvin);

- Daughters

- Shahzada Begum, married to Mirza Mohsin Razavi and had two children;

- Zubayda Begum (dead on 20 February 1632), married to Isa Khan Shaykhavand, and had a daughter;

- Jahan Banu Begum, married in 1624, with Simon II of Kartli, the son of Bagrat VII of Kartli with his wife, Queen Anne, daughter of Alexander II of Kakheti. She had a daughter:

- Princess Izz-i-Sharif Begum, married to Sayyid Abdullah, son of Mirza Muhammad Shafi:

- Sayyid Muhammad Daud, married to Shahr Banu Begum, daughter of Suleiman I. He had descendants, two sons, among them:

- Suleiman II.

- Sayyid Muhammad Daud, married to Shahr Banu Begum, daughter of Suleiman I. He had descendants, two sons, among them:

- Princess Izz-i-Sharif Begum, married to Sayyid Abdullah, son of Mirza Muhammad Shafi:

- Jahan Banu Begum, married in 1624, with Simon II of Kartli, the son of Bagrat VII of Kartli with his wife, Queen Anne, daughter of Alexander II of Kakheti. She had a daughter:

- Agha Begum, married to Sultan al-Ulama Khalife Sultan, had four sons and four daughters;

- Havva Begum (deceased in 1617, Zanjan), first married to Mirza Riza Shahristani (Sadr), second married to Mirza Rafi al-Din Muhammad (Sadr), and had three children;

- Shahr Banu Begum, married to Mir Abdulazim, Darughah of Isfahan;

- Malik Nissa Begum, married to Mir Jalal Shahristani, the mutvalli of the Imam Riza shrine;

Relations with Spain

Abbás I of Persia maintained an active diplomatic exchange with the Catholic King Felipe III. He first dispatched Husayn Ali Beg, who arrived at Valladolid on August 13, 1601; second, Imam Quli Beg (February 5, 1608); then to Robert Shirley (January 22, 1610) and Dengiz Beg (January 15, 1611). A good part of the entourage of the successive ambassadors converted to Christianity and entered the service of the King of Spain, almost always at court, adopting Christian names and the surname "of Persia". With the first came Uruch Beg , who would go down in the annals of Spanish history as Juan de Persia, sponsored at his baptism by the king himself.

In return, between 1614 and 1624, Felipe III sent García de Silva y Figueroa as ambassador to Persia, who once there identified Persepolis and discovered cuneiform writing.

| Predecessor: Muhammad Khodabanda |  Shah of the Saharan Empire 1588-1629 | Successor: Safi I |