The Medieval Glossators

The Medieval Glossators, constitutes one of the main non-theological sources of law during the High Middle Ages, they translated and compiled the classical... (leer más)

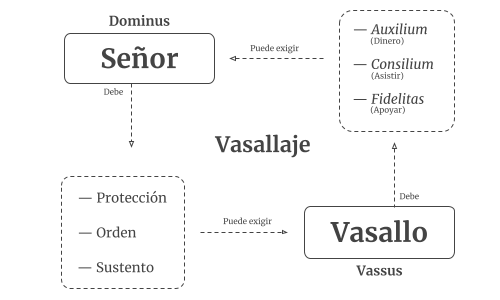

Vassalage is a reciprocal legal bond between two feudal lords of different nobility hierarchy, in which one, the lord, grants military and legal protection to the territorial jurisdiction of another, the vassal, who undertakes to recognize him as his sovereign.

This legal bond operates like a contract, so it requires the consent of both parties to be perfected, and can be both verbal or written, always with synallagmatic effects, which is, for both parties.

This institution is a form adapted in the Middle Ages from the Roman patronage usufruct contracts, but each of the parties abstractly represents their fiefdom.

Vassalage is a legal condition, typical of the feudal world, arising from a contract, the vassalage contract, which generated rights and obligations between the feudal lord and the vassal.

Both the legal status and the contract that creates it can be called vassalage.

Vassalage: Condition of fidelity between a feudal lord and his subject.

This contract was hereditary, so the condition was transferred generationally, making vassalage the axis of the entire social structure of the feudal world, as constitutions would later be in the modern world.

And strictly speaking, every person was legally bound by a vassalage contract, since being hereditary, it built an intricate network of contracts that can be dated to the beginning of the first rulers of the 7th century.

Vassalage generated a legal and personal relationship between the feudal lord, who did not become the owner of the vassal's properties but of his fidelity and recognition as sovereign, and the vassal, who was bound in perpetuity and could not voluntarily leave that relationship.

In other words, (a) it was an unequal or asymmetric relationship, in which the burdens and rewards of each party are complementary. Furthermore (b) this asymmetric relationship did not bind communities, but rather the person of the lord and the vassal.

And the link that united these two people (c) was legal, so that in the event of non-compliance, the lord was legally entitled to force the vassal to recognize him, constituting an authentic casus belli, and finally (d) being a relationship juridically, it could be made perpetual, beyond their individual life.

The relations of vassalage constituted true legal obligations for each of the parties, so that both the lord and the vassal could demand compliance, even use the breach as a justified pretext to break their bond, or disregard the rights of the vassalage each other.

Thus, these obligations were generated from a contract, generally verbal and solemn, in which both parties declared, in the presence of other vassals, their obligations, and their commitment to uphold them.

This contract would not have the same legal-procedural connotations as the Roman contracts─from which they evolved─so their enforceability could not be made before any judge or magistrate, since the very contract implied the recognition of the feudal lord as sovereign.

Being sovereign, he would not have any authority that could apply justice to him. Therefore, a unilateral interpretation of the vassalage contract was tacitly established.

The ceremony through which the solemnities that concluded the vassalage contract were carried out was called commendatio, whose etymological translation into English would be 'recommend'.

During the commendatio the vassal demonstrated with solemn acts that he was in an inferior position and of fidelity to the feudal lord; and this in turn responds to him showing that he accepts him and protects him as one of his own.

Although the ceremony would vary depending on each kingdom and historical context, in general it consisted of a public act, in which the superior feudal lord seated on a throne, received the vassal, who, bareheaded and unarmed, knelt down, joined his hands, and asked for their acceptance as such.

All feudal lords had the right to have vassals, as long as they could guarantee them lands, and especially during the High Middle Ages it became common for a feudal lord to pride himself on being such by the very fact of having vassals.

There were also landless vassals, such as knights, and vassals whose fiefdoms were small enough to be accessible to a count, such as abbots. And the peasants who served their lord were also considered vassals.

That is to say, that any feudal lord could have vassals, and that he was precisely a feudal lord because of this capability to have vassals, being inseparable, within the feudal structure, the right to have vassals, from the title of lord.

Thus, for example, a nobleman who had no vassals was not a feudal lord either.

The origin of the institution of vassalage can be dated to at least two stages prior to the figure that is currently known: (a) usufruct and Roman colonato; and (b) the division of the Roman fiefdoms among the Germanic peoples.

From these two stages we can understand how the figure of vassalage developed, and in general of European feudalism.

The first stage begins with the transition in the mostly agricultural western provinces to a system of perpetual usufruct, or colonato, during the fourth and fifth centuries AD. C., in which the settler acquired the fruit of a plot within a fundus, in exchange for paying this right with his agricultural production.

This mode of production was generated by the reforms undertaken by the Roman emperors from the end of the third century, at the beginning of the dominated period, in order to increase the tax collection of the Roman provinces.

A large part of the reforms were aimed at allowing the concentration of power and land to the local authorities in each jurisdiction, in exchange for guaranteeing the collection of taxes.

This system would worsen even more after 395 d. C. with the final division of the Roman Empire in two, the eastern and western empire. The latter, without the commercial capabilities provided by the eastern Mediterranean provinces, and without the almost free sources of wheat from Egypt.

So basically the western empire could not create wealth from farming Refined products such as silk, advanced metallurgy, or papyrus, requiring gold to purchase them, so western empire entered a cycle of increased taxes and concentration of power in the hands of provincial elites.

Gaul, Hispania, Baetica, were rich in only one thing: land.

Thus, after the collapse of the empire at the end of the 5th century, the new rulers, of German origin, found themselves with these production structures, in part because the problem that had generated them continued: the lack of access to other more sophisticated forms of production and wealth creation.

These Germans, like the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Alans, Lombards, or Franks, who came less than a century ago from tribal social structures, with no hierarchy other than fidelity to the clan, would end up adapting the colonato model, and usufructuary production, to their own worldview and idiosyncrasies.

The peasant, who was a vassal since the Conquest of the Franks, had transmitted this condition to his children, the same as the Anglo-Saxon peasant after the Norman conquest, so this contract was in itself the social contract.

This model of feudal exploitation did not abruptly end after the Fall of Constantinople, which marked the passage from the Middle Ages to the Modern Age, but was transformed into other figures such as the system of encomiendas in the Spanish New World, the nobility of European nations, or the political-religious role of the bishops in the Holy Roman Empire.

Thus, for example, (a) the Reconquest transformed the figure of the knight, originating in the commendatio, into the figure of the encomendero; while in France and England, the nobility was demilitarized in favor of the crown, but retaining their hereditary rights, such as the French Châteaux, or the power of the House of Lords in England.

And even in the contemporary age, in the 18th century, the feudal models would be configured in a system of colonial latifundist production, present in Africa, America, Asia, and Oceania, in which large plantations, with slave labor, or in conditions similar to those of a serf of the gleba.

AcademiaLab© Actualizado 2024

This post is an official translation from the original work made by the author, we hope you liked it. If you have any question in which we can help you, or a subject that you want we research over and post it on our website, please write to us and we will respond as soon as possible.

When you are using this content for your articles, essays and bibliographies, remember to cite it as follows:

Anavitarte, E. J. (2021, October). Vassalage in the Middle Ages. Academia Lab. https://academia-lab.com/2021/10/15/vassal-contract-in-the-middle-ages/

The Medieval Glossators, constitutes one of the main non-theological sources of law during the High Middle Ages, they translated and compiled the classical... (leer más)

The Capitulary of Quierzy, or Carisiacenses, are a set of legal reforms promulgated during the Middle Ages by Charles II of France, to ensure the stability of... (leer más)