The Accession in Roman Law

The accession is an original way of acquiring property in which, when two things are mixed, the property of the accessory thing passes to the owner of the... (leer más)

Inheritance or succession is any way of acquiring property, in which the new owner assumes rights and duties of the previous owner, to wit, he not only acquires something, but take place as owner.

On this, Roman law distinguished two periods for the use of the term succession: (a) at classical law, when the only viable form of succession was inheritance, and therefore succession and inheritance would be the same; and (b) at Justinian law, in which forms of succession for singular things were created.

But, despite the emergence of singular successions, even today this term almost always implies an acquisition per universitatem ex mortis causa, that means, a due to death succession. However, it is important to understand that texts with a different approach can be found.

Successions can be defined from a single characteristic: continuity in the exercise of things ownership, but this should not be confused with the derivative methods of acquiring property, which are not always given by succession, nor by inheritances, since not every succession is an inheritance.

Succession: legal act by which a Roman continued the rights and obligations of another.

[1]

Successions in general, serve to distinguish the exercise of rights of the new owner, for example, in the case of evictions, because in the absence of a previous successor, there are no reciprocal rights arising from the succession act.

The best example of this is a property, which in one case is succeeded by will, and in another, occupied on vacant land (we assume outside of Roman jurisdiction). In both cases there is an effective case of material apprehension of the thing (naturalis possessio), but, only in the case of the will, the deceased could limit the exercise of the successor, stipulating conditions, such as donating a part of its harvest to a temple.

Nihil est aliud "hereditas" quam successio in universum ius quod defunctus habuit.

("Inheritance" is nothing other than a succession of universal law over the properties of the deceased)

Gaius [2]

(Translation of the author*)

Thus, successions provide the property right with a timeline, which is legally useful for the subsequence acts derived from the exercise of property.

[1]: Succession | Glossary of Roman law.

[2]: Gaius | Digest: Lib. 50, Tit. 16, Sec. 24.

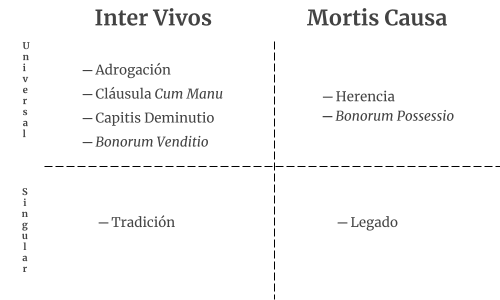

Successions in Roman law can be classified into four groups, which can be paired two by two. The first group corresponds to the personality of the deceased, whether he is alive or dead, since the successor will always be a living person; and the second group refers to the proportion of goods that are transferred, whether it would be done for all assets, or it would be done for delimited goods.

In general, most of the succession modes correspond to derivative methods of acquiring property. Except in cases where the method for acquiring property is unilateral and between living people, such as acquisition by law, or usucapion.

Due to death successions can be divided into two large groups, on the one hand (a) when they occurred on the universality of the assets and rights of the deceased, which we call inheritance or bonorum possessio, and on the other (b) when they occurred over a part of the assets to what we call legacy.

The word inheritance comes from the Latin Hereditas, and it was the first figure created by way of uses and customs, to be able to transmit the assets and rights that the paterfamilias had sustained in life, then with the publication of the Law of the XII tables, it became part of written civil law.

By inheritance can be understood both, the mass of assets that the deceased left universally, as well as the subjective right that each of the heirs have to claim a part or all of the inheritance mass. Therefore, one of the main characteristics of inheritance is to require an heir who has vocation to be able to claim.

Inheritance, which was a well-developed figure in Roman law, could have three types of heirs depending on their ability to reject the inheritance mass, which we remember could also include the debts of the deceased.

The necessary heirs owe their name to a legal figure in which a person, lacking heirs, designated an own slave as heir, thereby also generating his manumission. This was especially important in cases where the deceased had such an amount of debts that no one would accept their inheritance, and could lose their family cult and their name be branded as infamy.

Thus, even if the slave were to receive an inheritance without being able to refuse it, the benefit of being manumitted was so great for the slave, that this figure was undoubtedly seen as equitable.

By 'own' it was understood all the heirs who belonged to the family nucleus of the deceased at the time of his death, that is, those who lived under his domus. If they already enjoyed the assets that the deceased left, they tacitly accepted the inheritance, and they gave continuity to his personality.

When the deceased did not have an own heir, nor was he interested in leaving a slave in charge of his assets or debts, the rest of the heirs were called volunteers, since they could decide whether or not to accept the inheritance, as we remember the inheritance was not always benefits for their heirs, and sometimes debts exceeded the value of assets, in what would be named a hereditas damnosa.

Bonorum possessio is in strict sense a way of possession, a possession by "bona fides", and in the case of mortis causa inheritance, it occurs when a mass of inheritance assets has been caused, but no heir or legatee is presented to appropriate it, in accordance with the civil law.

Then, the praetor to make up for this lack of a manager of the property, which had to be well-kept and remain productive, appointed by edict a possessor in bona fides. For this possessor, bona fides was confirmed by the peaceful occupation of the assets caused, without opposition from any other interested in the assets.

Being a possessor in bona fides, they were exposed to lose the property if a legitimate heir appeared to claim it, but they could also acquire the assets by usucapion in case they fulfilled the necessary terms, since possession in bona fides enables them to do so, becoming a full owner.

When the transfer of the inheritance is not carried out over a universal basis, but covers a limited set of assets or rights, the figure of due to death succession was called legacy. The legacy always fulfills the characteristic of being an accessory clause to the will, which is why it is an express provision of the deceased.

Before addressing any succession issue, even in current law, the meaning acquired by the terms succession and inheritance, which are not necessarily the same, must be distinguished, although they can almost always be used as synonyms.

The succession is a common denomination that some methods of acquiring property receive, all having as characteristic the transmission of rights and responsibilities of the transferor, towards the acquirer.

Hence, we seldom see it classified as a method of acquiring property, since it is more than a method, a way of acquire obligations. In other words, things can be acquired by succeeding or not, the transferor, so succession does not necessarily designate the method in which they were acquired, but the responsibility acquired for the new owner.

All this, at least for the ancient Roman law.

And on the other hand, inheritance is only a type of succession, which operates when a person dies, so as not to leave without legal personality the mass of assets that are, for Romans, an extension of the personality of the deceased. [¶]

In short, inheritance is a type of succession.

In addition, of being distinguished to inheritance and successions, it is also distinguished from the term per universitatem, since the one ─ succession ─ designates the responsibility acquired by the new owner, while the other ─ universitatem ─ the dimension of the acquired assets.

Because of what, someone can succeed to another, totally or partly, in a given legal relationship.

For example, inheritances are universal successions, while legacies constitutes a singular succession, or successio in singulas res.

And successions cannot be too resembled to derivative acquisitions, since there are derivative acquisitions that are not at all a succession, such as the in iure cessio, in which the magistrate sanctions another for the ownership of something, but this other is not a legal continuity from the previous owner, but a brand-new owner. [¶]

AcademiaLab© Actualizado 2024

This post is an official translation from the original work made by the author, we hope you liked it. If you have any question in which we can help you, or a subject that you want we research over and post it on our website, please write to us and we will respond as soon as possible.

When you are using this content for your articles, essays and bibliographies, remember to cite it as follows:

Anavitarte, E. J. (2019, June). Successions in Roman Law. Academia Lab. https://academia-lab.com/2019/06/24/successions-in-roman-law/

The accession is an original way of acquiring property in which, when two things are mixed, the property of the accessory thing passes to the owner of the... (leer más)

The Roman Law was the set of legal manifestations that were in force during the existence of Ancient Rome, between the years 753 BC until 476 AD and they were... (leer más)

The Code of Justinian or Codex Iustinianus is a systematic compilation of legislation applicable in the Eastern Roman Empire during the time of Emperor... (leer más)