The Medieval Glossators

The Medieval Glossators, constitutes one of the main non-theological sources of law during the High Middle Ages, they translated and compiled the classical... (leer más)

The mancipatio was a solemn way of acquiring property in the Roman civil law, which consisted in the control transferring of something through the simulation of a real market sale, by using a balance and a piece of copper.

It is considered a legal fiction because the copper and balance are not used to weigh the real value of the payment, but to give the solemnity of a legal sale to the mancipatio, and afterward the payment could be made in any other way.

This mode of transferring ownership had the symbolic result of declaring that the sale had been fully consummated, because of the payment of a weighed metal piece, and in presence of witnesses. Thus, the sale was─in addition to being effective─honorable.

To define the mancipatio, it must be understood that it is a peculiar mode of acquiring property of the Romans, and therefore, it incorporates ritual elements closely linked to their worldview, such as: (a) the sense of property as an absolute right, or (b) a faithfulness in the words of the witnesses.

Mancipatio: Solemn way of transferring property between Roman citizens using a balance and a copper piece.

HSD

For this reason, it was the quintessential way to transmit property between Roman citizens, during the archaic and pre-classic periods, in which the sources of rights were restricted in their applicability; Thus, for the tradition of non-daily goods among Roman citizens, only the mancipatio or the in iure cessio could operate.

Est autem mancipatio, ut supra quoque diximus, imaginary quaedam venditio: Quod et ipsum ius proprium civium Romanorum est […]

(For the rest, the mancipation is, as we said before, a kind of imaginary sale: which, and for himself, is proper to the right of Roman citizens)

Gayo [1]

(Translation from the author*)

[1]: Gayo | Institutions: Lib. 1, Para. 119.

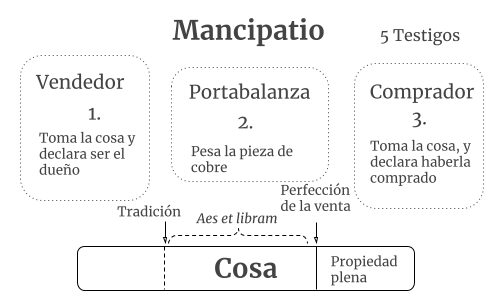

For the sale by mancipation to be perfected, it required the performance of a series of solemn acts, through which the intention of the transferor and the buyer of the thing was unequivocally demonstrated, to carry out the legal business.

Thus, the buyer, the seller, five witnesses and a balance carrier (libripens) met in a certain place, and the seller, with the thing in hand, as in a real sale, had to declare that it was his by legitimate right as a Roman citizen.

[…] Eaque res ita agitur: Adhibitis non minus quam quinque testibus civibus Romanis puberibus et praeterea alio eiusdem conditionis, qui libram aeneam teneat, qui appellatur libripens, is, qui mancipio accipit […]

(And this is done like this: summoned no less than five witnesses, Roman citizens and pubes, and another one of the same condition, who holds a copper scale, which is called a balance carrier, and who receives the thing to be mancipated)

Gayo [2]

(Translation from the author*)

Then he gives the thing to the buyer, who now declares to be its legitimate owner before the witnesses, for having bought it according to civil law, paying its fair price, through copper and the balance; and strikes the scale with the piece of copper, and then hands it over to the seller "the piece of copper."

After this act, the sale was taken for granted, and in the event of any claim from either party, the witnesses attested to a legitimate sale.

[…] Rem tenens ita dicit: HUNC EGO HOMINEM EX IURE QUIRITIUM MEUM ESSE AIO ISQUE MIHI EMPTUS ESTO HOC AERE AENEAQUE LIBRA […]

(Having the thing says like this: I HERE, MAN, I AFFIRM THAT IT IS MINE BY THE CHIRITARY RIGHT, AND THAT IT WILL BE PURCHASED FROM ME FOR THE COPPER WEIGHT OF THE BALANCE)

Gayo [3]

(Translation from the author*)

In the case that it was a property, the physical presence of the thing was not required to attest neither the property, nor its existence, nor its transfer, but the seller could either celebrate the act in the same property, or good to carry something that represents you, such as a tile.

The mancipatio, which has its origin in the traditions of fair sale of the quirites, or ethnic Romans, is performed through a procedure called per aes et libram (using copper and scales). For these cultures, the balance and the transfer of heavy metals in it represents a sale (a) certain, (b) fair, and therefore (c) legitimate.

So, at the time of demonstrating this quality, for any good that was not already so easy to weigh, such as slaves, draft animals, or rustic houses, the Romans pretended to make a sale of these characteristics, except that the thing did not it was necessarily weighed with the balance, but rather a metal, generally copper or bronze, which served as payment.

[2]: Gayo | Op. Cit.

[3]: Gayo | Op. Cit.

Mancipation was typical of mancipi assets, so it did not operate in cases of res nec mancipi, giving this legal act an exclusively Roman nature.

Even the division between mancipi goods and nec mancipi goods is based on whether or not they can be transferred by mancipation. Being a rare case in which the legal figure gives names to things, and not the other way around. Gayo is very clear about this:

Mancipi uero res sunt, quae per mancipationem ad alium transferuntur; unde etiam mancipi res sunt dictae. quod autem ualet mancipatio, idem ualet et in iure cessio.

(In contrast, mancipi things are those that are transferred to someone by manipulation, which is why they are called mancipi. That is, they are allowed by manipulation, and they are also allowed by in iure cessio)

Institutions [4]

(Translation from the author*)

The act of using a scale and a piece of copper (per aes et libram) had a connotation, not only legal, but also sacred, about the act of delivery, because it implied a fair payment ─between Roman citizens─ for the thing.

Hence, it was also used for other legal fictions, such as in the case of the liberation of a person by means of the mancipium, or the testament per aes et libram.

Since the mancipatio was excluded from the ius civile, not just anyone could use it to transfer assets, since it constituted protection for those assets─the mancipi─that had greater social importance within the civitas.

This symbolic act represents the archaic custom of taking something with the same hands, this being an irrefutable proof of ownership: having paid for it, and having it in their hands. We can see this explanation in the writings of Isidore of Seville (ca. 630):

Mancipatio dictates est quia manu res capitur […]

(It is called mancipation since it is grasped with the hand)

Etymologies [5]

(Translation from the author*)

[4]: Gayo | Institutions: Lib. 2, Para. 22.

[5]: Isidoro from Seville | Etymologies: Lib. 5, Para. 31.

The main effect that the sale by mancipation─mancipation─would have, is that it disposed of the asset, which immediately became part of the property of the acquirer. Thus, even if the property was not present, as in the case of rustic properties, the domain was considered to have been transferred.

Although this effect of transfer of property had a limitation, another legal fiction in the case of the mancipatio of family children, who could also be sold per aes et libram.

In these cases, it was simulated that the "property" of the child was transferred, from the father to a third party, but always with the promise that it would be returned to him after a term or a condition made in the sale.

As it was not a requirement that the property was always in the act of mancipatio, but this transferred ipso iure the property, the acquirer took the action of vindicatio, to materially possess the thing that had been sold to him.

Now, the buyer also acquired the right to claim from the seller in the event of an eventual eviction, since the only proof that the seller has is the word that the seller has given him "only" that the thing is his.

This action that enabled the buyer to pursue the seller, as a debtor in case of being deprived of the peaceful possession that should have been given, is the actio empti.

Although in general, the mancipatio procedure operates to transfer ownership of things, there is a particular exception to this legal effect arising from the sale per aes et libram. When the object of the sale is not a thing, [¶] but a family child, only the right to command over it is perfected.

Thus, although it is also in the strict sense a sale, this sale generally has an implicit condition that resolves it after a period of time, either by the course of the same time, or by the necessary sale of the acquirer─again─to the father of the child, some conditions fulfilled.

This allowed a father to dispose of his children, so that they could work under the command of another free person, as they should do for their own father, and in a similar way to the sale of a slave.

Hence, it is said that the alieni iuris were in a position of quasi-slavery, but with the exception that, since there was such a special blood bond with the father, the person of the son was returned by force of habit.

This is also the source of emancipation, which is nothing other than a sale for mancipatio repeated three times, between the father and a third party. For that is how it was established in the Law of the XII Tables: whoever sold his son three times lost all rights over him.

The mancipatio, as a form of solemn transmission of property, had three characteristics: (a) on the one hand, it was exclusive to the ius civile, which implies that only Roman citizens could make use of this means to acquire or dispose of.

On the other (b) the mancipatio was essentially a fiction, that is, it was a solemnity that recreated the way in which a legitimate sale would have to be, but without requiring the real tradition of the goods object of the sale, as it would have been the case of a mere tradition.

And finally, (c) this way of acquiring property is solemn, that is, failure to comply with the procedures necessary to perfect the mancipatio, naturally results in the nullity of the act. If it was sold between citizens, simulating─precisely─an ordinary sale, but without the presence of witnesses, there would no longer be a mancipatio.

The things mancipi (res mancipi), in general, are all those things that the Romans could acquire through mancipatio.

That is to say, its distinction is not due to any factor inherent in the thing, but to the discretion that the Romans made as to what could, or could not, be sold in a solemn way.

Since most of the things that can be sold for mancipatio, the same things that were of greater importance for agricultural societies of the middle of the Iron Age, such as: (a) rustic lands, (b) slaves, or (c) agricultural work animals; all of them aimed at allowing the exploitation of the land.

Although the mancipatio is the most notorious way of showing the particularities of Roman law, in terms of the creation of new legal institutions, the truth is that its scope was rather limited.

This institution only operated for the transfer of assets whose social value merited the creation of a complete legal entity, and not mere tradition. Figure also linked, with the possession of the ius commercium. In general, we count four assets that can be acquired by mancipatio: (a) the estates in Italy, (b) their easements, (c) the slaves, and (d) the working animals.

Therefore, after the territorial expansion of the empire, and especially during the period of the Principality, when Rome had access to the agricultural resources of the largest fertile areas of the Mediterranean coasts, such as Egypt, the banks of the Guadalquivir, or the area of the Galia Narbonensis, agriculture would cease to be the main activity of the city, and with it, the mancipatio would fall into disuse.

But this abstract idea would continue, which gave rise to the mancipatio: the possum mancipi, and which corresponds to the ability to create rights over things, not according to the nature of things, but that of those who use them.

Specifically, regarding citizenship and the legal capacity to negotiate with them, or to acquire them legitimately.

AcademiaLab© Actualizado 2024

This post is an official translation from the original work made by the author, we hope you liked it. If you have any question in which we can help you, or a subject that you want we research over and post it on our website, please write to us and we will respond as soon as possible.

When you are using this content for your articles, essays and bibliographies, remember to cite it as follows:

Anavitarte, E. J. (2018, April). The Mancipatio in Roman Law. Academia Lab. https://academia-lab.com/2018/04/06/mancipatio-in-roman-law/

The Medieval Glossators, constitutes one of the main non-theological sources of law during the High Middle Ages, they translated and compiled the classical... (leer más)

Edicts were the official pronouncements that Roman magistrates, on the strength of their faculty of ius edicendi, made to the... (leer más)

Agnation is a form of kinship characteristic of Romans, and exclusive of their civil law, it was generated by being subject to the parental authority of the... (leer más)