The Senatus Consulta in Roman Law

The senateconsults, or senatus consulta, were the set of acts uttered by the senate in which they examined some matter placed under their... (leer más)

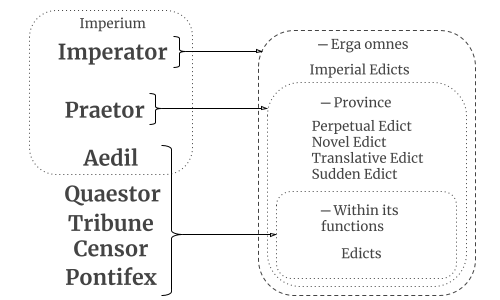

Edicts were the official pronouncements that Roman magistrates, on the strength of their faculty of ius edicendi, made to the public.

In general, the largest source of edicts in Roman law came from the praetors, since they had to invoke each year which rules they were going to have as reference for their trials. This work of publicity of the content of edicts resulted in the emergence of the ius honorarium.

As early as the Roman imperial era, edicts published by the emperor were relevant enough, and at the provincial level the edicts of the governors ruled like that of the emperor himself.

HSD

The concept of edict for the Romans can be better understood from an etymological perspective, than from a strictly legal one, edictum is a substantiation of the verb edicere whose meaning in English: proclaim. From where the edict implied a proclamation, a manifestation, a publication, made by some Roman magistrates qualified for it.

Edict: Any provision a Roman magistrate makes public in use of the ius edicendi.

Although there is no unambiguous definition of the term in the writings that we know of the Roman world, it is known that its legal force would be fully binding, as can be seen in one of the definitions from Paulo:

Illa verba "optimus maximusque" vel in eum cadere possunt, qui solus est. sic et circa edictum praetoris "supremae tabulae" habentur et solae.

(That expression "what is fully perfect" or what can fit in it, means: what is univocal. So similar to the praetorian edict that is considered "supreme statute" and univocal.)

Digest [1]

(author's translation*)

[1]: Paul | Digest: Vol. 50, Tit. 16, Sec. 163.

Edicts were classified according to the magistrate who issued them, and the competence that they manifested, so we can find: praetorial edicts, imperial edicts, censorious edicts and the others.

But of all these, only two were legally relevant, (a) the edicts issued by the praetor, since they constituted true law applicable to new cases, and (b) the edicts issued by the prince ─imperator─, which constituted law by his authority.

However, and to conceptually delimit the scope of what an edict is, it must be taken into account that all magistracies could issue edicts, and that the ius edicendi was not an exclusive prerogative, but rather a broad one. [¶]

The praetor, who was in charge of administering justice, had to keep the people more informed of how to interact with him, since it is a constant and unpredictable function, being their cases different each one.

For this reason, each year the new praetor published an edict, called perpetual, because it was permanently exhibited ─perpetual─ in which the people were communicated with the formulas that should be used for their dispatch, the legal solutions that they considered pertinent, and in general the way in which justice could be accessed.

This edict was made up of two parts, (a) a new one, which formulated the new legal innovations that the praetor added, and (b) a previous one, in which what the new praetor gave as valid from the previous praetor was established, this anterior part was called translative.

It should be noted that the term of the magistracy of the praetor was one year.

But the praetor could also issue edicts that constituted only the new part or the translative part, which we call new edicts and translative edicts.

And in force of his pretura, he could always have new extraordinary criteria to attend to his cases, which we call sudden edicts.

Thus, the edicts that the praetors issued because of their functions were (4) four: (a) perpetual edicts, (b) new edicts, (c) translative edicts, and (d) sudden edicts.

Although only one really constitutes part of the ius honorarium, the so-called perpetual edict, since the other three are rather internal edicts, which served either to specify or to modify the perpetual edict.

The perpetual edict is the form par excellence of the praetorian edict, due to the obligation that they had to make public the criteria that they would have to resolve the cases, the sources that they would have as true when they could not be clear, ─as jurisconsults─, and the information that citizens should know to access a trial.

The perpetual edict had to be published every year, at the beginning of the pretura, and remained visible in the forum, outside the office of the praetor, until the same or the next praetor changed it.

It seems that it existed shortly after the magistracy of the praetor was created (366 BC), and this tradition lasted until the fall of the western Roman Empire, but had a moment of significant change, when Hadrian (131 AD) requested to Salvio Juliano, the publication of a perpetual edict for all the praetors.

So it ceased to be a dispositive faculty of the praetor, and each one had only to copy and paste the same perpetual edict of Hadrian.

Although it is called Edict, it really constituted the part of the Perpetual Edict where the forms, actions and solutions proposed by the previous praetor were welcomed.

Although it is called Edict, it really constituted the part of the Perpetual Edict where forms and solutions were provided that had not been raised by the previous magistrate and that the new praetor was going to consider as legal references.

The sudden edict was the one issued by the praetor when he developed new judgment criteria, which were not already reflected in the perpetual edict, and which should be published before the following year to inform the citizens that it would be a decision criterion. These were published together with where the perpetual edict was.

The Roman emperors were formally a magistracy, so they had the ability to issue edicts as part of their powers, these edicts were called imperial edicts, and they had a binding force equal to that of Roman law, coming from a magistracy with jurisdiction over the entire Roman state.

The imperial edicts immediately became part of the imperial constitutions, and their process should not ordinarily be annual, but were occasional. To better understand the imperial edicts, one must understand the figure of the imperial constitutions.

After the advent of Empire, the publication of perpetual edicts by praetors became routine, with each praetor issuing virtually the same perpetual edict as his predecessor; even more so by the new power of the emperor (princeps), who had unified legal criteria with his power of intercessio.

Thus, the emperor Hadrian around the year 130 d. C. ordered the jurist Salvius Julianus to create a single perpetual edict, which the praetors could use one after another, according to the guidelines of the office of the emperor, to which Julianus added the nova clausula Juliani on succession issues for the emancipated.

After its publication, a senatorial resolution officially confirmed the power of the new perpetual edict of Hadrian─or of Salvius Julianus─which caused that presidents of the provinces in each jurisdiction to publish their own edictum provinciale to regulate the content of the perpetual edict of the propraetors of their jurisdiction.

The ius edicendi was an accessory prerogative to the position of magistrate, so any magistrate could, by virtue of this right, publish those norms that would operate for their office, making them public.

Ius autem edicendi habent magistratus populi Romani. Sed amplissimum ius est in edictis duorum praetorum, urbani et peregrini

(For their part, the magistrates of the Roman people have the right to decree edicts. But this very broad right is in the edicts of both praetors, urban and pilgrim)

Gaius [2]

(author's translation*)

Therefore, it seems that in principle, the figure was born more, as a way to publicize the work of the magistrates, than to really create law. Hence, its fulfillment was due to the figure of the magistrate itself, that is, to the ius honorum.

However, the magistracy of the praetor, when setting for it the procedures that would operate, created de facto right, since the parties had to be certain in order to solve their disputes, what the praetor required of them to access his office.

So the ius edicendi acquired this double connotation: (a) on the one hand it publicized the work of the magistrate, but on the other (b) it created true legal norms contained in these publications.

[2]: Gaius | Institutions: Vol. 1, Para. 6.

AcademiaLab© Actualizado 2024

This post is an official translation from the original work made by the author, we hope you liked it. If you have any question in which we can help you, or a subject that you want we research over and post it on our website, please write to us and we will respond as soon as possible.

When you are using this content for your articles, essays and bibliographies, remember to cite it as follows:

Anavitarte, E. J. (2016, October). The Edicts in Roman Law. Academia Lab. https://academia-lab.com/2016/10/28/edicts-in-roman-law/

The senateconsults, or senatus consulta, were the set of acts uttered by the senate in which they examined some matter placed under their... (leer más)

Plebiscites were all those legal acts, which as a whole, the plebs uttered in their assemblies, or assemblies of the plebs to regulate their own law, at... (leer más)

The Medieval Glossators, constitutes one of the main non-theological sources of law during the High Middle Ages, they translated and compiled the classical... (leer más)